Hōei eruption facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hōei eruption |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Volcano | Mount Fuji |

| Type | Plinian eruption |

| Location | Chūbu region, Honshu, Japan 35°21′29″N 138°43′52″E / 35.3580°N 138.7310°E |

| VEI | 5 |

Map of volcanic ash fall during the Hōei eruption

|

|

The Hōei eruption of Mount Fuji was a powerful volcanic event. It began on December 16, 1707, and lasted until February 24, 1708. This eruption was the last confirmed time Mount Fuji erupted. It happened during the rule of Emperor Higashiyama and the Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi.

The Hōei eruption is famous for the huge amount of ash it spread across eastern Japan. This ash caused many problems, including landslides and severe food shortages. The area where the eruption happened is now called Mount Hōei. This name comes from the Hōei era, which was the time period when the eruption occurred.

Today, you can visit the main crater of this eruption. It is accessible from the Fujinomiya or Gotemba Trails on Mount Fuji. The famous artist Hokusai even included an image of a small crater from this eruption in his work, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji.

Contents

The Hōei Eruption: Mount Fuji's Last Big Blast

What Happened During the Hōei Eruption?

Early Warning Signs and Explosive Power

Before the Hōei eruption, there were signs that Mount Fuji was waking up. Three years earlier, in 1704, rumbling sounds were heard for a few days. Then, about one to two months before the eruption, strong earthquakes shook the area around the volcano. Some of these quakes were as strong as magnitude 5. Scientists believe these earthquakes were connected to the eruption that followed.

The Hōei eruption was a type called a Plinian eruption. This means it was very explosive. It shot out pumice (light, porous rock), scoria (dark, bubbly rock), and ash high into the stratosphere. The stratosphere is a layer of Earth's atmosphere. This material then rained down far to the east of the volcano.

After the eruption, heavy rainfall caused lahars. Lahars are dangerous mudflows made of volcanic ash and water. Scientists think that two different types of magma (molten rock inside the Earth) mixed together. This mixing might have happened because of the earthquakes.

Ashfall and New Vents on Mount Fuji

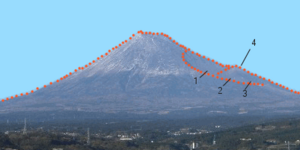

The eruption created three new openings, or vents, on Mount Fuji's east-southeast side. These are called Hōei vents No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3. The eruption unfolded over several days. It started with an earthquake and an explosion of ash. Days later, more rocks and stones were thrown out with great force. This event caused the worst ashfall disaster in Japan's history.

Even though no lava flowed, the Hōei eruption released about 800 million cubic meters of volcanic ash. This ash spread over huge areas around the volcano. It even reached Edo (now Tokyo), which is almost 100 kilometers away. In Edo, the ash was several centimeters thick.

Ash and cinders fell like rain in many provinces, including Izu, Kai, Sagami, and Musashi. Ashfall was also recorded in Tokyo and Yokohama. The ash covered many crops, stopping them from growing. The eruption was rated a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which measures how explosive eruptions are.

How the Hōei Eruption Affected People

Food Shortages and River Problems

The Hōei eruption had a terrible impact on the people living near Mount Fuji. The tephra (all the material ejected from the volcano) caused farming to decline. This led to severe food shortages for many people in the Fuji area. Volcanic ash covered many farm fields east of Mount Fuji.

To clear their fields, farmers moved the volcanic material into large piles. But then, rain washed this material from the piles into rivers. This made some rivers shallower, especially the Sakawa River. Huge amounts of ash fell into this river, creating temporary dams. In August 1708, heavy rainfall caused an avalanche of volcanic ash and mud. This broke the dams and flooded the Ashigara plain.

Many of the problems after the Hōei eruption were due to flooding, landslides, and lack of food. Crops failed because ash covered the fields. This caused widespread food shortages in the Edo area. Large rocks, floodwater, and ash made it hard for people to move. This led to even more suffering from hunger in the Edo area.

Why Did the Hōei Eruption Happen?

Earthquakes and Magma Movement

Scientists believe two major earthquakes caused the Hōei eruption. These were the 1703 Genroku earthquake and the 1707 Hōei earthquake. The Genroku earthquake was a magnitude 8.2 quake. It happened at the Sagami Trough, a deep underwater valley. The Hōei earthquake was even stronger, around magnitude 8.6 or 8.7. It occurred at the Nankai Trough 49 days before the eruption.

The Genroku earthquake was the biggest ever recorded at the Sagami Trough. It helped set the stage for the eruption. The Hōei earthquake then squeezed the magma chambers (pools of molten rock) under Mount Fuji. This pressure pushed the magma, leading to the eruption.

How Magma Rose to the Surface

Underneath Mount Fuji, there is a system of cracks called a dike system. This system goes from the surface down 20 kilometers. About 8 kilometers deep, there are magma chambers with different types of magma. Deeper down, there is basaltic magma. The dike system acts like a pathway for magma to reach the surface.

The Genroku earthquake changed the pressure on this dike system. It squeezed the dike and the magma inside, trapping it. The magma chambers were compressed, and the dike bent, holding the magma in place. Then, the Hōei earthquake allowed the magma to force its way up to the surface.

The Hōei earthquake also affected the dike system. It increased pressure in the upper part of the dike, keeping some magma trapped. But in the lower, southeastern part of the dike, the pressure lessened. This allowed the basaltic magma, which was still being squeezed, to rise. It mixed with the trapped magma. This mixing caused the magma to expand with gas bubbles. This expansion helped the magma travel to the surface, causing the Hōei eruption.

Mount Fuji's Future: A Sleeping Giant?

Japan's Tectonic Plates and Volcano Monitoring

Japan is in a very active part of Earth called the Ring of Fire. This area is known for many volcanoes and earthquakes. Mount Fuji sits where three tectonic plates meet: the Eurasian Plate, the Okhotsk microplate, and the Philippine Sea Plate. This is why the region has so much geological activity.

Scientists have been monitoring Mount Fuji closely. In 2012, they measured the pressure inside the volcano. Based on this, they believe another eruption is possible. There have been many earthquakes since the 1707 Hōei earthquake. Minor activity was seen in the 1980s, 2000, and 2001. The major Tohoku earthquake in 2011 also occurred, though it was further away. After the activity in 2000, scientists found that magma was collecting under the volcano.

What Could Happen in a Future Eruption

If another eruption happened, the damage could cost Japan over US$25 billion. Scientists expect that a future eruption, like the Hōei eruption, might happen at the same vents.

A repeat of the 1707 Hōei eruption could affect over 30 million people. These people live in crowded areas like eastern Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and parts of Yamanashi, Saitama, and Shizuoka. Tokyo would likely be hit hardest. An eruption could cause power outages, water shortages, and problems with the city's advanced technology.

Mount Fuji has more than 20 stations that monitor seismic activity. These stations watch for any ground movement. It is impossible to know exactly when the next eruption will happen. However, because Mount Fuji has been quiet for a long time, scientists expect it to erupt again.

See also

In Spanish: Erupción del monte Fuji de la era Hōei para niños

In Spanish: Erupción del monte Fuji de la era Hōei para niños

- 1707 Hōei earthquake

- Historic eruptions of Mount Fuji

- Mount Hōei

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |