Harald Kreutzberg facts for kids

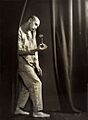

Harald Kreutzberg (born December 11, 1902 – died April 25, 1968) was a famous German dancer and choreographer. He was known for a dance style called Ausdruckstanz, which means "expressive dance." This style focused on showing strong feelings and emotions through movement. Even though he is not as well-known today, he was one of the most famous German male dancers of his time.

Contents

Becoming a Dancer

Kreutzberg was born in a place called Reichenburg, which is now Liberec in the Czech Republic. His family later moved to different cities in Germany. His father and grandfather were circus performers, so he grew up around entertainment. His mother encouraged his love for acting and theater. When he was just six years old, he performed at an operetta house in Dresden.

Harald also studied art at the Academy of Applied Art in Dresden and was a talented artist. He was very interested in costumes and fashion. To help his family, he even designed women's clothes for a local store. In 1920, he performed a dance at a student party that was so popular, he decided to take dance lessons.

He trained at the Dresden Ballet School and learned from important dancers like Mary Wigman and Rudolf von Laban. These teachers were pioneers of Ausdruckstanz, a dance movement that became very popular in German-speaking countries. This style was part of a larger movement that promoted healthy living and physical activity.

In 1923, Harald joined the Municipal Opera Ballet in Hannover. He wasn't always comfortable dancing in a large group. The opera director noticed his talent for acting and gave him special character roles. Later, when the ballet director, Max Terpis, moved to the Berlin State Opera, he invited Kreutzberg to join him.

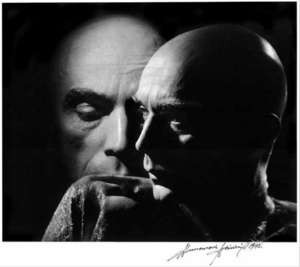

In 1926, Kreutzberg played the role of Fear in a ballet called Die Nächtlichen. The next year, he danced as an unusual jester in Don Morte, a ballet based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe. For this role, he shaved all his hair off to look bald, which made a big impression. He kept this bald look for the rest of his life! This performance also started his long partnership with Friedrich Wilckens, who was his composer and piano player.

In 1927, a famous theater director named Max Reinhardt cast Kreutzberg in plays in Salzburg. Later, Harald played Puck in a New York production of A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1929.

Dancing with Yvonne Georgi

In 1928, Harald Kreutzberg worked with Wilckens and Yvonne Georgi on a funny dance show called Robes, Pierre and Co.. Yvonne Georgi was another talented dancer who had studied with Rudolf von Laban. In this show, they used sounds like typewriters and gunshots, and Kreutzberg even sang in a high voice!

Between 1929 and 1931, Kreutzberg and Georgi toured all over Europe and the U.S. They became very popular and helped introduce Ausdruckstanz to many people. Audiences loved their performances. People said Kreutzberg had amazing stage presence and seemed much taller than he was. He filled the whole stage with his dramatic energy.

Their shows included solo dances by each of them, as well as duets. Their dances were modern and focused on strong, athletic movements. They both enjoyed showing off their physical skills.

Some of their most famous dances included:

- Fahnentanz: A "mirror dance" where they wore Roman-like costumes with large capes that they waved like flags.

- Hymnis: A serious, ceremonial dance with music by Lully.

- Pavane: A very serious dance with music by Ravel. They wore glowing white costumes and moved slowly in the dark.

- Persiches Lied: A slow dance with music by Satie, performed in striking costumes. They moved together, wrapping around each other and ending covered by a veil.

In 1931, they performed a huge show in Berlin to Gustav Holst's The Planets. The stage had a big, abstract set with ramps and slanted walls. Even when they were far apart, their movements connected them. In a funny dance called Potpourri, they wore polka-dot costumes and joked around with their pianist, Wilckens. They would interrupt his playing and dance like children, until he got annoyed and left, making them follow him off stage.

American critics praised Georgi, but they were especially amazed by Kreutzberg. They said he had a unique way of moving and a powerful ability to express himself.

Pictures of Kreutzberg and Georgi were even printed on cigarette cards as part of a collection of "Famous Dancers." Other famous dancers like Anna Pavlova and Josephine Baker were also in this collection.

Dancing with Ruth Page

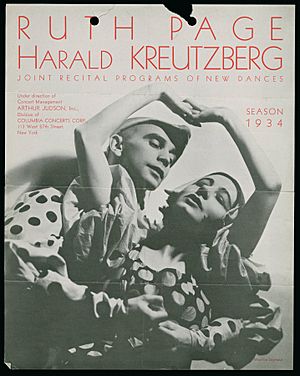

After touring with Georgi, Kreutzberg had a few short dance partnerships. In 1930, he and Wilckens met Ruth Page, an American ballet dancer, on a ship. They became good friends.

In 1933, Page and Kreutzberg started a new and surprising dance partnership. It seemed unusual for a ballet dancer and a modern German dancer to work together. But this partnership helped both of them. Page gained a modern, international style and the musical support of Wilckens. Kreutzberg found new places to perform and a way to escape the difficult political situation in Germany.

They performed their first show together on February 25, 1933, in Chicago. Each dancer did solos, then they performed a duet, just like Kreutzberg had done with Georgi. Their U.S. tour in 1933 was so successful that they repeated it the next year, and then toured Japan and China in 1934.

Some of their most popular dances were:

- Country Dance: A folk-style ballet with peasant costumes, bonnets, and puffed sleeves.

- Promenade: A graceful dance with music by Poulenc, where they used elegant hand movements.

- Bolero: A very popular dance that audiences loved and that sold out shows.

- Bacchanale: An experimental dance with music by Gian Francesco Malipiero. It had unusual movements like repeated falls and dancing back-to-back. They wore black costumes with white elastic bands on their faces and bodies.

Their partnership eventually ended. Kreutzberg might have wanted to focus on his solo shows. Also, Ruth Page became the ballet director for the Chicago Grand Opera Company. After 1936, it became harder for American artists to work with German artists because of the political situation. In 1939, the German government stopped Kreutzberg from traveling, and his shows were canceled. Despite this, Kreutzberg and Page remained friends for many years.

Ruth Page later said that dancing with Kreutzberg was the happiest time of her life. She felt he was one of the greatest influences on her career.

His Role During World War II

The rise of the Nazi government in Germany greatly affected dance. Some dancers stayed in Germany and worked with the Nazis, while others left the country. Kreutzberg was one of the few dancers who kept a good relationship with the government's propaganda ministry. He understood how to continue his dance career during this time. In the 1920s and 1930s, his performances sometimes showed a strong sense of national pride, which fit with the government's ideas.

Kreutzberg was at the peak of his career during World War II. In 1937, he was the main dancer at German Art Week in Paris. In 1939, he performed at the Day of German Art in Munich. His performances often followed where the German army advanced. For example, after the Netherlands was taken over in 1940, he gave recitals there. Some people called him "the dancing ambassador of National Socialist Germany."

From 1942 to 1944, dance and music concerts were organized in Dutch cities for German soldiers. The public could also attend. News of Kreutzberg's shows was used for propaganda. For example, a weekly newsreel in Dutch cinemas showed a clip of him dancing on a beach. A German-funded newspaper also published a full-color photo of him.

Even though many gay men faced harsh treatment during this time, Kreutzberg was allowed to tour Germany and other countries. His long-term musical partnership with Wilckens was widely known.

The 1936 Berlin Olympics

The German government held dance festivals before the Olympic Games in 1936. These festivals aimed to set rules for "acceptable dance" and promote a unified artistic style. The propaganda minister hosted the first festival in 1934, and it became an annual event leading up to the Olympics.

For Nazi Germany, the Olympics were a chance to show off their national strength. They wanted to include dance in the games because Germany was strong in that area. While dance wasn't officially added to the Olympics, an international dance competition was held. Rudolf von Laban organized this event, and Kreutzberg and Mary Wigman helped him. They were asked to create dances that fit the government's ideas.

Kreutzberg's dance for the Olympics was called Waffentanz (Weapons Dance) or Swerttanz (Sword Dance). It was more like a theatrical show than a traditional dance. It started with 60 young men, representing two groups with swords, rushing into the stadium. They had a mock battle, and one group won. Kreutzberg then performed a solo dance that ended with his character's heroic death. Both Kreutzberg's and Wigman's dance groups received Olympic medals.

Interestingly, this spectacular dance performance was not included in the famous documentary film about the 1936 Olympics, Olympia, because the filmmakers felt there wasn't enough light to film it well.

Paracelsus Film

In 1943, when it seemed Germany might lose the war, Kreutzberg appeared in a movie called Paracelsus. He played a character called Der Gaulker (The Juggler) Fliegelbein. In the film, his character, who is already sick, sneaks into a city during a plague.

Kreutzberg performed a short, but amazing, dance scene in the movie. It was like a "dance of death" (Totentanz). His movements were confusing and wild. He would move forward and back, hopping, then marching stiffly. He seemed to lead the people in the tavern who watched him, showing a mix of confusion and wild energy. This scene was so powerful that some people called it one of the best ballet performances ever filmed.

Military Service

In 1944, Kreutzberg was drafted into the German Army. He was soon captured by American forces in Italy and spent about two and a half months in a prisoner of war camp. He later wrote that he had a "good time" there, performing scenes from A Midsummer Night's Dream and playing characters from the play Faust. After he was released, he returned to Germany and continued his international dance career.

Solo Career and Later Years

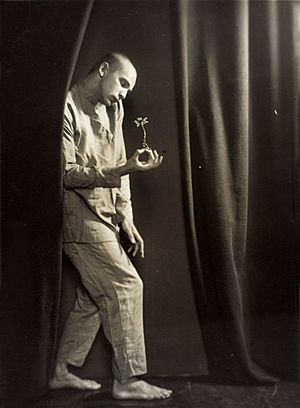

From 1936 onwards, Kreutzberg mostly performed solo. Some people compared him to the famous dancer Nijinsky. Kreutzberg's style was modern, with sharp, angular, and twisting movements. His solo dances usually fell into two types: charming and funny character dances, often using masks, and emotional dances that showed deep feelings. He performed everything from sad stories like The Angel Lucifer to funny ones like The Wedding Bouquet. Even in his serious dances, he often had the image of a jester or a playful acrobat.

He created his own unique dances, combining free movements with elements of theater, like mime and special costumes. Like Martha Graham, he designed most of his costumes, and many photographs show how creative they were.

Kreutzberg performed solos in the U.S. in the early 1930s, and again in 1937, 1947, 1948, and 1953. A dance critic from The New York Times, John Martin, was a big fan of Kreutzberg. Martin helped him regain his reputation after World War II. Martin wrote that Kreutzberg mostly tried to stay out of sight during the war.

After the war, Kreutzberg remained a leading figure in German modern dance. He was one of the first German artists to tour internationally, performing in the U.S., South America, and Israel in 1948. Famous choreographer George Balanchine even invited him to share a program with the New York City Ballet. He toured many European countries every other year. His last performance in the Netherlands was in 1958. In 1965, he made his last U.S. appearance with the Lyric Opera of Chicago, dancing the role of Death in Carl Orff's Carmina Burana.

He also appeared in a few films and TV shows. In the 1960s, he was featured on U.S. television in a short version of The Nutcracker, playing both Drosselmeyer and the Snow King.

In 1955, he opened a dance school in Bern, Switzerland. After he stopped performing on stage in 1959, he continued to create dances for others and teach until he passed away on April 25, 1968.

His Impact on Dance

From the beginning of his career, Kreutzberg focused on expressive dance. He stuck to this style throughout his life, but he also knew how to please audiences. Because of this, he helped make modern dance popular around the world.

Harald Kreutzberg was a complex person. He was an artistic innovator, but he also worked with the Nazi government. His supporters say he only cared about his art and wasn't interested in politics. However, he continued his career without interruption under the Nazis and was used to promote their cultural ideas. He was one of the most respected and highest-paid artists in Nazi Germany. He often included feminine movements and costumes in his performances, challenging traditional ideas of male dancers.

When asked about his dance philosophy, Kreutzberg said that dancers need to master technique, but then use their minds to express feelings through their bodies. He saw himself as a "storyteller and painter" through dance.

His expressive dance style influenced dancers in the U.S. as well. Dancers like Erick Hawkins and José Limón saw him as a major influence on male modern dancers, at a time when most famous modern dancers were women. He was also an important link to choreographers like Alwin Nikolais and Hanya Holm.

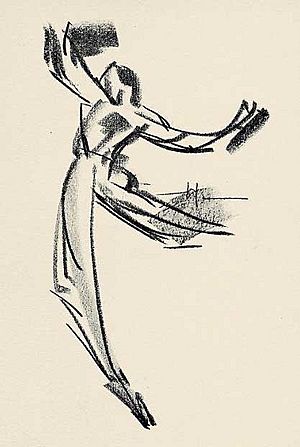

In 1933, a book of twenty-four charcoal drawings of Kreutzberg dancing was published. These drawings focused on his body movements rather than his facial features, showing his strength, emotion, and energetic actions like leaping, running, and twisting.

He was the subject of three German television documentaries, including a full-length film in 1961.

Today, Kreutzberg's original dances are rarely performed. However, in 2012, a dancer named John Pennington recreated one of his 1927 solos called Dances Before God. In 2015, a group called DanceLab Berlin created a new show called H.K. – Quintett as a tribute to him. They explored questions about identity, gender, and the role of male dancers today, using elements from Kreutzberg's movements.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Harald Kreutzberg para niños

In Spanish: Harald Kreutzberg para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |