Helmuth Hübener facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Helmuth Hübener

|

|

|---|---|

Helmuth Hübener, flanked by Rudolf "Rudi" Wobbe (left) and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe (right)

|

|

| Born | 7 January 1925 |

| Died | 27 October 1942 (aged 17) Plötzensee Prison, Berlin, Nazi Germany

|

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Known for | Youngest anti-Nazi German to be put to death for resistance |

Helmuth Günther Guddat Hübener (born 8 January 1925 – died 27 October 1942) was a brave German teenager. He was executed at just 17 years old for speaking out against the Nazi government. He was the youngest person in the German resistance to Nazism to be sentenced to death by the special Nazi court and executed.

Contents

Helmuth's Early Life

Helmuth Hübener was born in Hamburg, Germany, on 7 January 1925. His family was not involved in politics and was religious. They belonged to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His adoptive father, Hugo, supported the Nazis and gave Helmuth the last name Hübener.

From a young age, Helmuth was a Boy Scout. This group was supported by his church. However, in 1935, the National Socialists (Nazis) banned scouting in Germany. Helmuth then had to join the Hitler Youth, as the government required. But he left the Hitler Youth after Kristallnacht in 1938. During Kristallnacht, Nazis, including the Hitler Youth, destroyed Jewish businesses and homes.

Helmuth disagreed when a leader in his church tried to stop Jews from attending services. He kept going to church with friends who felt the same way. His friend, Rudi Wobbe, who also resisted the Nazis, said that most church members in Hamburg were against or not involved with the Nazis.

Speaking Out Against the Nazis

In 1941, after finishing middle school, Helmuth started an apprenticeship. This was like a training job in administration. He worked at the Hamburg Social Authority. There, he met other young people, including Gerhard Düwer, who later joined his resistance group.

Helmuth also met new friends at a bathhouse. One of them came from a family that believed in communism. Through this friend, Helmuth started listening to radio broadcasts from other countries. At that time, listening to foreign news was strictly forbidden in Nazi Germany. It was seen as a serious crime against the country.

In the summer of 1941, Helmuth found his older half-brother's shortwave radio. Helmuth began listening to the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) on his own. He used the information he heard to write anti-Nazi messages and anti-war leaflets. He made many copies of these papers.

The leaflets showed people how the official news from Berlin about World War II was wrong. They also pointed out the bad actions of Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Helmuth's writings also talked about how pointless the war was and that Germany would likely lose. He even mentioned how members of the Hitler Youth were sometimes treated badly.

In late 1941, Helmuth's friends, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, Rudi Wobbe, and later Gerhard Düwer, joined him. They helped him spread about 60 different pamphlets. These papers had typed information from the British radio broadcasts. They distributed them across Hamburg. They would secretly pin them on bulletin boards, put them in mailboxes, and even slip them into coat pockets.

Arrest and Execution

On 5 February 1942, the Gestapo (Nazi secret police) arrested Helmuth. This happened at his workplace in Hamburg. He was trying to translate the pamphlets into French. He wanted them to be given to prisoners of war. A co-worker and Nazi Party member, Heinrich Mohn, saw him and reported him to the police.

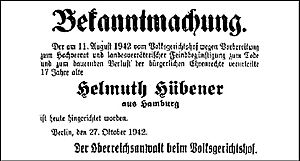

On 11 August 1942, Helmuth, at 17 years old, was put on trial. He was tried as an adult by the Special People's Court in Berlin. This court handled cases of treason. Helmuth was sentenced to death. After hearing his sentence, Helmuth bravely told the judges: "Now I must die, even though I have committed no crime. So now it's my turn, but your turn will come." He hoped his words would make the judges angry at him, saving his friends from a harsh sentence.

The court said Helmuth was guilty of planning high treason and helping the enemy. He was sentenced to death and lost all his civil rights. This meant he was treated very poorly in prison. He was not allowed bedding or blankets in his cold cell.

It was very unusual for the Nazis to sentence a teenager to death. But the court said Helmuth was smarter than most boys his age. They believed his intelligence and knowledge meant he should be punished like an adult.

Helmuth's lawyers, his mother, and the Berlin Gestapo asked for mercy. They hoped his sentence would be changed to life in prison. They argued that Helmuth had confessed everything and was still a good person. However, the Nazi Youth Leadership disagreed. They said Helmuth's actions were too dangerous to Germany's war effort. So, the death penalty was necessary.

On 27 October 1942, the Nazi Ministry of Justice confirmed the death sentence. Helmuth was told of this decision only a few hours before his execution. At 8:13 pm on that day, he was killed by a guillotine at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. His two friends, Schnibbe and Wobbe, were also arrested. They received prison sentences of five and ten years.

Church Reaction to Helmuth

In 1937, the leader of the LDS Church, Heber J. Grant, visited Germany. He told church members to stay in Germany, get along, and not cause trouble. Because of this, some church members saw Helmuth as a troublemaker. They thought he made things difficult for other Latter-day Saints in Germany.

The local church leader, Arthur Zander, supported the Nazi Party. He put a sign at the church entrance saying "Jews not welcome." Ten days after Helmuth's arrest, on 15 February 1942, Zander claimed to have removed Helmuth from the church. Other church leaders also supported this decision.

On the day he was executed, Helmuth wrote a letter to a friend from his church. He wrote, "I know that God lives and He will be the Just Judge in this matter… I look forward to seeing you in a better world!" This is believed to be the only letter by Helmuth that still exists.

In 1946, after the war, Helmuth was brought back into the LDS Church. The new church leader, Max Zimmer, said that Helmuth's removal from the church was not done correctly. Helmuth was also later rebaptized and given other church blessings. This made it clear that his membership in the church was never truly in doubt.

Helmuth's Legacy

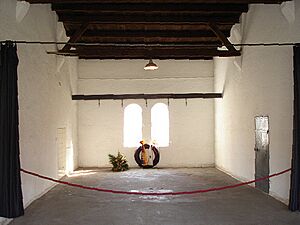

Today, a youth center, a school, and a pathway in Hamburg are named after Helmuth Hübener. The pathway is in Sankt Georg. At the former Plötzensee Prison in Berlin, there was an exhibit about Helmuth's resistance and execution. People often place flowers there to remember Helmuth and others killed by the Nazis. Helmuth also has a Stolperstein, which is a small memorial stone, at Sachsenstraße 42 in Hamburg-Hammerbrook.

On 8 January 1985, 60 years after Helmuth's birth, Hamburg city officials held ceremonies to remember him. His friends who resisted with him, Schnibbe and Wobbe, had moved to the U.S. after the war. They returned to Hamburg for the event and were honored guests and speakers.

Helmuth's Story in Books and Films

Helmuth Hübener's story has been told in many books, plays, and movies.

In 1979, Thomas F. Rogers wrote a play called Huebener. It has been performed many times. Helmuth's two friends, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe and Rudi Wobbe, even attended some of the shows.

The book When Truth Was Treason (1995) tells the story from Karl-Heinz Schnibbe's point of view. Another book, Hübener Vs. Hitler by Richard Lloyd Dewey, is a biography that includes interviews with Helmuth's friends and family.

Rudolf Gustav Wobbe, Helmuth's other friend, wrote Before the Blood Tribunal (1989). This book shares his personal experience of being tried by the Nazi court and his time in prison. It was later republished as Three Against Hitler.

The 2008 novel The Boy Who Dared by Susan Campbell Bartoletti is a fictional story based on Helmuth's life. Bartoletti's earlier book, Hitler Youth: Growing Up in Hitler's Shadow (2005), also talks about Helmuth's story.

Helmuth's story was also shown in the 2003 documentary film Truth & Conviction. Another independent film, Resistance Movement, was made in 2012. In 2020, an exhibition about Helmuth Hübener by German artist Cordula Ditz took place at Kunsthalle Hamburg.

See also

- List of peace activists

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |