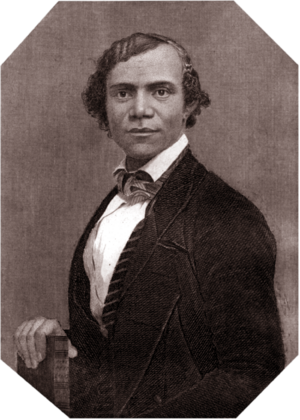

Henry Bibb facts for kids

Henry Walton Bibb (born May 10, 1815, died August 1, 1854) was an American writer and abolitionist. He was born into slavery in Shelby County, Kentucky. Bibb shared his life story in a book called The Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb: An American Slave. This book described his many attempts to escape slavery, until he finally succeeded and reached Detroit.

After moving to Canada with his family, Bibb started an anti-slavery newspaper called Voice of the Fugitive. He lived in Canada until he passed away.

Contents

Henry Bibb's Early Life and Escapes

Henry Bibb was born on May 10, 1815. His mother, Mildred Jackson, was enslaved. His father was Senator James Bibb. Henry's six brothers and sisters were sold to different owners. Henry was hired out by his father for his wages. He wanted to learn to read the Bible. He got some education at a school run by Miss Davies, but the school was soon closed down.

When Henry was young, he saw the Ohio River as a big barrier to his freedom. He often looked across it, wondering how he could cross. He knew that if he made it over, he could be free in Canada. But crossing seemed almost impossible.

Bibb wrote about his first marriage in his book. He met Malinda when he was 18. She lived on a nearby plantation in Oldham County, Kentucky. Henry quickly fell in love with her. They both dreamed of being free. So, they decided to wait a year before marrying. In 1833, Henry and Malinda got married. They soon had a daughter named Mary Frances.

Henry's many escape attempts kept him away from his family for long periods. At one point, he successfully escaped to Canada. But he came back to try and free his family. He was captured again. After his final escape, he tried to find out what happened to Malinda.

Around 1837, Bibb escaped to Cincinnati, Ohio. Six months later, he returned to free his wife. But he was caught and enslaved once more. Bibb and his daughter were sold to a slaveholder in Vicksburg, Ohio. After another failed escape, Bibb was sold to Cherokee people near the Kansas-Oklahoma border.

Bibb's experience with the Cherokee slaveholder was the most positive he described. Because of this, Bibb did not name this owner in his book. This was the only owner whose name he left out. Bibb believed that Native American slaveholders were different. He thought they grew crops for their own use. Southern slaveholders, however, grew crops to sell for profit.

Becoming an Abolitionist Leader

In 1842, Bibb finally escaped to the Second Baptist Church in Detroit. This church was a station on the Underground Railroad. It was run by Rev. William Charles Monroe. Henry hoped to free his wife and daughter. But he learned that Malinda had been sold. After this, Bibb focused on becoming an abolitionist. Monroe taught him to read and write.

Bibb traveled and gave speeches across the United States. He worked with famous abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and William Wells Brown. He strongly supported the Underground Railroad. In 1846, he helped Lewis Richardson cross into Amherstburg, Canada. Bibb was also a member of the Liberty Party.

In May 1847, Bibb met his second wife, Mary E. Miles. They married in June 1848. In 1849-1850, he published his autobiography. It was called Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made things more dangerous for Henry and his wife, Mary E. Miles. This law made it illegal to help escaped slaves. To stay safe, the Bibbs moved to Canada with Henry's mother. They settled in Sandwich, Upper Canada, which is now Windsor, Ontario.

In 1851, Henry Bibb started the first Black newspaper in Canada. It was called The Voice of the Fugitive. This newspaper helped create a more welcoming environment for Black people in Canada. It also helped new arrivals adjust to their new lives.

Henry and Mary E. Bibb also helped manage the Refugee Home Society. They helped start this group in 1851 with Josiah Henson. Mary also opened a school for children.

Because he was a famous writer, Bibb was reunited with three of his brothers. They had also escaped slavery and made it to Canada. In 1852, he published their stories in his newspaper. Henry Bibb died on August 1, 1854, in Windsor, Canada West. He was 39 years old.

It is interesting to note that slavery was officially ended in Canada on August 1, 1833. This date was, and still is, a national holiday in Canada.

Henry Bibb's Impact and Legacy

Henry Bibb is best known for his life story and many escape attempts. He wrote about these in his book. But Henry Bibb's work did not stop after he gained his freedom. He spent the rest of his life helping the Underground Railroad. Later, he wrote about ending slavery while living in Canada.

Bibb mainly helped on the route from Detroit to Canada. This route crossed the Detroit River. Enslaved people would escape to Detroit, where they were safer. From there, they could either stay or cross the river to Canada. Bibb worked very hard to help this cause. He helped make the Detroit River area a safe place and a symbol of freedom for African Americans escaping slavery.

Even after Bibb moved to Canada, he continued to help those escaping slavery through his writings. His book, The Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, made sure his story would always be remembered.

Bibb's Thoughts on Slavery

Superstitions Among Enslaved People

In his book, Henry Bibb wrote about the superstitions that enslaved people believed in. He said that many enslaved people, including himself when he was young, believed in witchcraft. Bibb thought that most people who claimed to use witchcraft were just pretending. But he knew that most enslaved people truly believed in it.

Bibb shared two times when he felt tricked by these "conjurers." He believed they were only after money. One time, he tried to win a woman's love. Another time, he tried to use a conjurer's advice to make a successful escape.

After these failures, Bibb seemed to stop believing in such superstitions. He realized that believing in these things came from the lack of education enslaved people received.

Fear of Being Called a Liar

In the last part of Bibb's book, he shared a fear. He worried that people would accuse him of making up parts of his story. He made it clear that none of his stories were exaggerated. He said that slavery was so terrible that it could not be exaggerated. It was "the peak of dread."

Henry Bibb as an Underground Railroad Agent

When Bibb worked as an agent for the Underground Railroad, he lived in Detroit. But his work often took him back and forth between Detroit and Canada. He crossed the Detroit River many times. Bibb's job included crossing the river with people escaping slavery. He also met others on the Canadian side of the river. We know about Bibb's work with the Underground Railroad from letters he wrote. Other letters were written about him during his time as an agent. Bibb also wrote more details in his own publications.

A Letter from Elder Binga (1846)

A letter from Elder Binga, published on April 24, 1846, tells about a successful escape. It describes how Bibb helped a man named Lewis Richardson, who was from Kentucky. Bibb led Richardson across the Detroit River to Canada. Once Richardson was safe, Bibb celebrated his freedom by singing him a song called "The Fugitive's Triumph."

A Letter from Henry Bibb to John Calkins (1850)

Henry Bibb wrote a letter from Windsor on June 19, 1850, to a man named John Calkins. This letter is still available to read online.

This three-page letter describes how Bibb gave money to enslaved people fleeing to Canada. This letter clearly shows Bibb's important help with the Underground Railroad.

Letters in Bibb's Book

The end of Bibb's book includes letters and parts from his newspaper, Voice of the Fugitive.

Letter to James G. Birney (1845)

Bibb wrote to James G. Birney, another abolitionist. Birney had said that Bibb might not be telling the whole truth in his book. Bibb explained that he was telling the truth. He thanked Birney for his honest review. He admitted that he might have forgotten some dates. This made some people think he was not honest. Bibb wanted to prove that he was telling the truth.

Letters to His Old Master

Henry Bibb wrote two letters to Albert G. Sibley, one of his former masters. He wrote the first letter on September 23, 1852. When he did not get a reply, he wrote another on October 7 of the same year.

In the first letter, Bibb told Sibley that he was not a true Christian. Bibb also told Sibley that his siblings, who had escaped from Sibley's plantation, were now free with him in Canada. Bibb continued the letter by describing the terrible acts of slavery. He said these acts went against God's word.

In the second letter, Bibb again told Sibley that to be a true Christian, he must stop owning slaves. Bibb argued against the common idea that freed slaves could not take care of themselves. He pointed out that enslaved people took care of themselves, their masters, and the plantations they lived on. Bibb ended the letter by saying that if Sibley tried to deny anything he said, he would provide proof. He also added a note saying that if Sibley kept ignoring his letters, he would send more.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Bibb para niños

In Spanish: Henry Bibb para niños

- List of enslaved people