Henry James Sr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry James Sr.

|

|

|---|---|

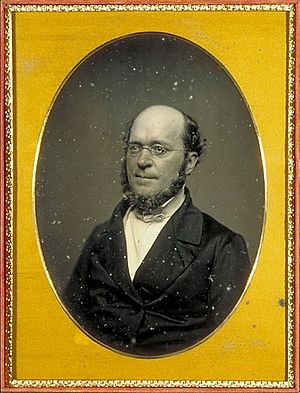

Daguerreotype of James, c. 1855

|

|

| Born | June 3, 1811 Albany, New York, U.S.

|

| Died | December 18, 1882 (aged 71) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Education | Union College Princeton Theological Seminary |

| Occupation | Theologian |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Robertson Walsh

(m. 1840; died 1882) |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

Henry James Sr. (born June 3, 1811 – died December 18, 1882) was an American thinker and writer. He was the father of some very famous people. His son William James became a well-known philosopher. Another son, Henry James, was a celebrated novelist. His daughter, Alice James, kept a famous diary.

Henry James Sr. had a powerful spiritual experience that changed his life. After this, he became very interested in a belief system called Swedenborgianism. He believed that focusing too much on money and things was wrong. He thought people should follow a path to spiritual goodness. He often disagreed with other thinkers of his time. He preferred talking about his ideas with friends rather than in public. He once said, "I love the fireside rather than the forum," meaning he liked quiet talks more than big public speeches.

Contents

Henry James Sr.'s Early Life

Henry James Sr. was born in Albany, New York, on June 3, 1811. He was one of twelve children. His father, William James, came from Ireland. William became very rich from business deals in New York. He made his money from real estate, lending money, and helping build the Erie Canal.

When Henry was thirteen, he had a bad accident. He was trying to put out a barn fire and severely burned his leg. Doctors had to remove his leg. He spent three years recovering in bed. This time made him even more focused on studying. He went to Union College in 1828 and finished in 1830.

His father was a strict Presbyterian and didn't like Henry's religious ideas. But when his father's will was changed, Henry became wealthy on his own. He studied at Princeton Theological Seminary from 1835 to 1837. He planned to become a minister. However, he found the ideas there too difficult and gave up on that dream. After Princeton, he traveled to England for about a year. He returned to New York in 1838.

Henry James Sr.'s Career and Ideas

When James returned to New York in 1838, he worked on a book by Robert Sandeman. This book was about a Scottish religious group that disagreed with the Presbyterian Church. James believed it showed "Gospel truth" better than other works.

Exploring Swedenborgianism

Around 1841, James became interested in Swedenborgianism. He read articles by James John Garth Wilkinson, who later became a close friend. James also met Ralph Waldo Emerson, a famous American writer. But Emerson's ideas did not fully satisfy him.

Emerson introduced James to Thomas Carlyle, another important writer. However, James found his true spiritual home in the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Swedenborg was a Swedish scientist and religious thinker. In May 1844, while in England, James had a life-changing experience. He was sitting alone after dinner, looking at the fire. Suddenly, he felt a terrible, unexplained fear. He later called this a "vastation," a step in spiritual growth according to Swedenborg.

This experience caused a spiritual struggle for two years. He found peace by deeply studying Swedenborg's work and other Christian mystical writings. James became convinced that people's biggest problem was their focus on themselves. He believed this "selfhood" led to pride and bad opinions. He remained dedicated to Swedenborg's ideas for the rest of his life. He always carried Swedenborg's books with him when he traveled.

In 1845, James came back to the United States. He spent his life giving talks about his spiritual discoveries. He wrote many books explaining his thoughts.

Thoughts on Society

In the late 1840s, James became interested in Brook Farm. This was a community in Massachusetts where people tried to live together in a new way. He also studied Fourierism, a type of utopian socialism. This idea came from the French thinker Charles Fourier. James saw utopian ideas as a way to improve spiritual life.

James strongly criticized American society for being too focused on "material things" (money and possessions). He found Fourier's ideas helpful for this criticism. He didn't think highly of most famous writers of his time, except maybe Walt Whitman. Still, he met and talked with many of them. These included Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and William Makepeace Thackeray.

James supported many social changes. He wanted to end slavery and make divorce laws more flexible.

His Theological Views

James's religious ideas were different from many thinkers in the 1800s. He did not believe in naturalism, which often tried to explain religion through science. He thought creation was a "purely spiritual process." For him, the main religious problem was theodicy, which asks why there is evil in the world if God is good.

His solution, based on Swedenborg, was to separate God from nature. He believed true reality (God) is completely spiritual. People in the natural world can barely understand this. But by understanding this spiritual reality, James thought people could escape the false ideas of nature. These false ideas include time, space, and focusing on oneself. This escape, he believed, led to salvation. Evil, especially spiritual evil, came from acting based on the false idea of self-importance. James believed that "the principle of hell is selfhood and the principle of heaven is brotherly love." He wasn't a blind follower of Swedenborg. Instead, he found in Swedenborg the best way to explore his main idea: that all evil comes from being too attached to oneself.

Later Years and Influence

Many people in his time didn't like James's ideas. He also disagreed with the growing excitement for science. But he never gave up. In fact, some of his best writings came from his later years. He was very involved in his children's lives and helped shape their education. Many people enjoyed talking with him. They liked his conversations, even though he sometimes offered strong criticism. He loved using paradox (ideas that seem to contradict each other) and exaggerating. He also enjoyed going against common rules. But he avoided formal social gatherings. He found them uncomfortable. He wrote, "The bent of my nature is towards affection and thought rather than action. I love the fireside rather than the forum."

Henry James Sr.'s Family Life

On July 28, 1840, Henry James Sr. married Mary Robertson Walsh. She was the sister of a friend from Princeton. They were married in New York City. The couple lived in New York and had five children:

- William James (1842–1910): He became a famous philosopher and psychologist. He was the first person to teach a psychology course in the United States.

- Henry James Jr. (1843–1916): He was a well-known author. Many people consider him one of the greatest English-language novelists. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature several times.

- Garth Wilkinson "Wilkie" James (1845–1883): He married Caroline Eames Cary.

- Robertson "Bob" James (1846–1910): He married Mary Lucinda Holton.

- Alice James (1848–1892): She was a writer. Her diary became very famous after her death.

Henry and Mary had a happy marriage. When Mary died on January 29, 1882, Henry seemed to lose his desire to live. He stopped working on his books and became very sad. He felt a bit better after his sons visited him. But he got worse again after Henry Jr. and William left for trips to Europe. His famous sons never saw him alive again. He died on December 18, 1882, in Boston.

On the very day Henry Sr. died, his son Henry Jr.'s boat arrived in New York. Henry Jr. was on his way back to see his father. William James was in London at the time. His family kept the full truth about his father's health from him. They didn't want to ruin his much-needed vacation. Four days before his father died, William learned how sick he was. William wrote a very touching letter that his father never read. In it, William wrote:

In that mysterious gulf of the past into which the present will soon fall and go back and back, yours is still for me the central figure. All my intellectual life I derive from you; and though we have often seemed at odds in the expression thereof I'm sure there's a harmony somewhere, & that our strivings will combine. What my debt to you is goes beyond all my power of estimating,—so early, so penetrating and so constant has the influence. ... Good night my sacred old Father. If I don't see you again—Farewell! a blessed farewell!

Henry Sr. named Henry Jr. as the person in charge of his estate (his money and property). This caused some disagreement with his oldest son, William. In his will, Wilkie received less money than his brothers and sister. His father felt he had already given Wilkie enough money during his life, which Wilkie had lost in failed businesses. However, Henry, Alice, and Bob felt bad for Wilkie. He had a heart condition and rheumatic fever from injuries during the Civil War. So, they decided to share the estate equally. William strongly disagreed. He argued it was easier for Alice and Henry to give up more money because they didn't have their own families to support. This issue was not settled when Wilkie died in November 1883, less than a year after his father.

See also