Herm (sculpture) facts for kids

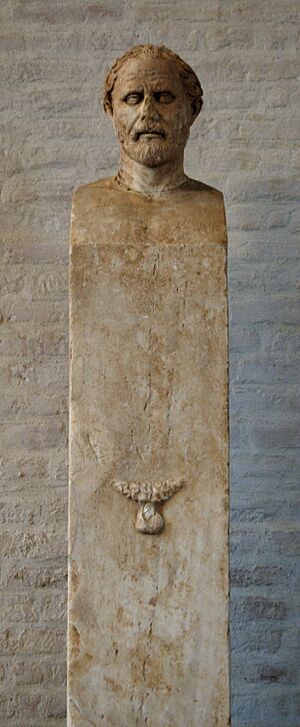

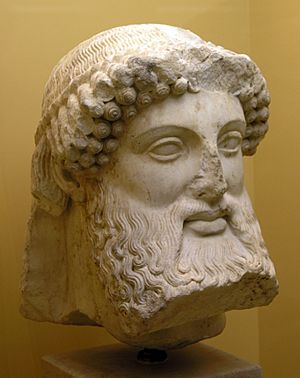

A herma was a special type of statue from ancient Greece. It usually had a square or rectangular pillar for a body and a head on top. Often, the head was of the Greek god Hermes, which is where the name "herma" comes from. These statues were also used by the Romans and became popular again during the Renaissance.

Contents

Understanding Hermae: Ancient Greek Statues

Where Did Hermae Come From?

Long, long ago in Greece, people sometimes worshipped their gods by placing piles of stones or simple stone or wooden pillars. You could find these stone piles along roads, especially where roads crossed, or at the edges of land. People showed respect for these stone piles by adding another stone or pouring oil on them as they passed by.

What Were Hermae Used For?

In ancient Greece, people believed these statues could keep away bad luck or evil. This is called an apotropaic function. Hermae were placed in many important spots:

- At road crossings

- On country borders

- In front of temples

- Near tombs

- Outside homes

- In gymnasia (places for exercise and learning)

- In libraries and public areas

- On high roads as sign-posts, sometimes with distances carved on them.

The heads on hermae were not always Hermes. They could be other gods, heroes, or even famous people. In Athens, where hermae were very common and respected, they were placed outside homes for good luck. People would rub them with olive oil and decorate them with wreaths. This tradition of touching statues for good luck still exists today, like with the Porcellino bronze boar in Florence.

Later, in Roman times and during the Renaissance, hermae often showed the body from the waist up. They were also used for statues of famous thinkers like Socrates and Plato. Sometimes, female figures were used, especially from the Renaissance onwards, often as decorations on walls.

A Famous Event: The Trial of Alcibiades

Vandalism in Ancient Athens

In 415 BC, something shocking happened in Athens. One night, just before the Athenian fleet was going to sail to Syracuse for a big war expedition (part of the Peloponnesian War), all the hermae in Athens were damaged. Many people thought this disrespectful act would bring bad luck and threaten the success of their mission.

People believed it was done by saboteurs, perhaps from Syracuse or by people in Athens who supported Sparta. One person suspected was a famous Athenian leader named Alcibiades. He said he was innocent and wanted to prove it in court. However, the Athenians did not want to delay the expedition further. His opponents also wanted him to be away so they could turn the public against him when he couldn't defend himself.

Hermae in Art and Stories

Modern Appearances of Hermae

The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles has a large collection of Roman herma boundary markers.

An Aesop's fable tells a funny story about a statue of Hermes. When a dog offers to "anoint" it (pour oil on it), the god quickly tells the dog it's not needed!

In the fantasy novel Lud-in-the-mist by Hope Mirrlees, the main character finds an important object by digging under something called both a "berm" and a "herm." It's described as "the tree yet not a tree, the man yet not a man."

Gallery

-

Small terracotta herma of Hermes

-

Herma on an Attic red-figure lekythos, 475–450 BC

-

A hermaic sculpture of an old man, probably a philosopher. Ai Khanoum, Afghanistan, 2nd century BC

-

Male and female Baroque hermae at the Rubenshuis

See also

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |