History of Fiji facts for kids

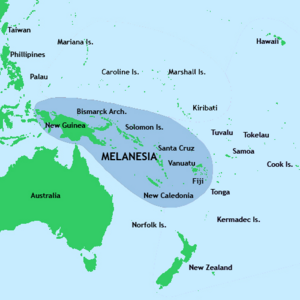

Most of Fiji's islands were created by volcanoes about 150 million years ago. Even today, you can still find some hot spots on the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni. The first people to live in Fiji were the Lapita people, around 1,500 to 1,000 BC. Later, many people with mostly Melanesian backgrounds arrived around the start of the Common Era. Europeans began visiting Fiji in the 1600s. After being a short-lived independent kingdom, Fiji became a British colony in 1874. It stayed a British colony until 1970, when it became independent. In 1987, after some military takeovers, Fiji became a republic.

In 2006, a military leader named Frank Bainimarama took control. When the High Court said his government was against the law in 2009, the President, Josefa Iloilo, cancelled the country's rulebook (the Constitution) and put Bainimarama back in charge. Later in 2009, Epeli Nailatikau became the new President. After many delays, a democratic election was finally held on 17 September 2014. Bainimarama's party, FijiFirst, won the election, and international observers said the election was fair.

Contents

- Early Life in Fiji: Settlers and Culture

- First Meetings with Europeans

- Cakobau and the Wars Against Christian Influence

- Attempts to Take Over Fiji

- Cotton, Groups, and the Kai Colo

- Kingdom of Fiji (1871–1874)

- Forced Labor and Slavery in Fiji

- Fiji Becomes a British Colony

- Independent Fiji

- Role of the Military

- See also

Early Life in Fiji: Settlers and Culture

Fiji is in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Its location made it a popular place for people to settle and a busy spot for travelers for many centuries.

Pottery found in old Fijian towns shows that people from Austronesia first settled Fiji around 1100–1000 BC. Later, Melanesians arrived about a thousand years after that. It's thought that the Lapita people, who were ancestors of the Polynesians, settled the islands first. We don't know much about what happened to them after the Melanesians arrived. They might have influenced the new culture, and some evidence suggests they moved on to places like Samoa, Tonga, and even Hawai'i.

Archaeological finds on Moturiki island show people lived there from 600 BC, and maybe even as far back as 900 BC. Some parts of Fijian culture are similar to Melanesian culture in the western Pacific. However, they also have strong links to older Polynesian cultures. People traded between Fiji and nearby islands long before Europeans came. For example, canoes made from Fijian trees have been found in Tonga. Also, some Tongan words are part of the language in Fiji's Lau Islands. Pots made in Fiji have been found in Samoa and even the Marquesas Islands.

In the 900s AD, the Tu'i Tonga Empire was formed in Tonga. Fiji became part of its influence. This Tongan influence brought Polynesian customs and language into Fiji. The empire started to become less powerful in the 1200s.

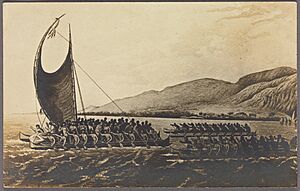

Fiji stretches over 1,000 kilometers from east to west. Because of this, it has been a nation with many languages. Fiji's history involved both people settling down and moving around. Over centuries, a unique Fijian culture grew. People built large, beautiful sailing boats called drua. Some of these were even sent to Tonga. Villages had special buildings, including shared and private houses called bure and vale. Important settlements often had strong walls and moats for defense.

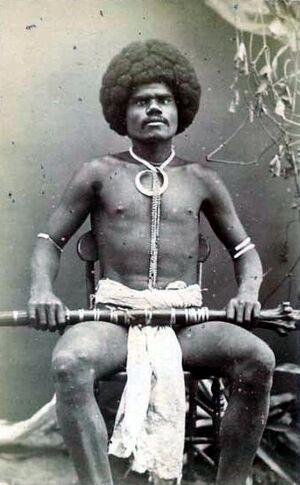

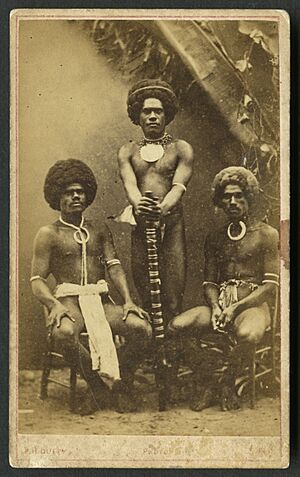

Fijians raised pigs for food and grew crops like bananas early on. Villages also got water through wooden pipes built for that purpose. Fijian societies were led by chiefs, elders, and brave warriors. Spiritual leaders, called bete, were also very important. They used and drank yaqona as part of their ceremonies and community gatherings. Fijians even had their own money system. Polished teeth from sperm whales, called tabua, were used as currency. A type of writing also existed, which you can still see in rock carvings around the islands. They also made masi cloth, which is a woven bark material used for sails and clothes. Men often wore a white cloth around their waist called a malo and a turban-like head covering. Women wore a neat, short skirt with fringes called a liku. Fijians also styled their hair in unique large, rounded shapes.

Like most early human groups, warfare was a big part of daily life in Fiji before Europeans arrived. They used weapons like decorated war-clubs and poisoned arrows. When Europeans and colonialism came in the late 1700s, many parts of Fijian culture were stopped or changed. This was done to make sure Europeans, especially the British, had control. This was particularly true for traditional Fijian spiritual beliefs.

First Meetings with Europeans

The first European known to visit Fiji was the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. He saw the northern island of Vanua Levu and the North Taveuni islands in 1643. He was looking for a large southern continent. He named these islands Prince William's islands and Heemskerck Shoals, which are now called the Lau group.

James Cook, a British sailor, visited one of the southern Lau islands in 1774. However, it wasn't until 1789 that the islands were properly mapped. This happened when William Bligh, the captain of the HMS Bounty (who was cast away), sailed past Ovalau and between the main islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. He was on his way to what is now Indonesia. The strait between the two main islands is named Bligh Water after him. For a while, the Fiji Islands were even known as the "Bligh Islands."

The first Europeans to have a lot of contact with Fijians were traders looking for sandalwood, whalers, and traders of "beche-de-mer" (sea cucumber). In 1804, sandalwood was found on the southwestern coast of Vanua Levu. This led to more Western trading ships visiting Fiji. A rush for sandalwood started, but it ended when supplies ran out between 1810 and 1814. Some Europeans who came to Fiji during this time were accepted by the local people and allowed to stay. One famous person was a Swede named Kalle Svenson, better known as Charlie Savage. Charlie and his guns were seen as helpful by Nauvilou, the leader of the Bau community, for their wars. Charlie was allowed to marry and become important in Bau society. In return, he helped them defeat local enemies. However, in 1813, Charlie was killed during a failed raid.

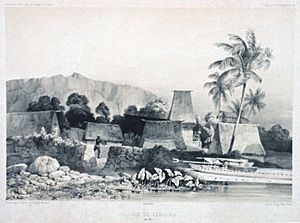

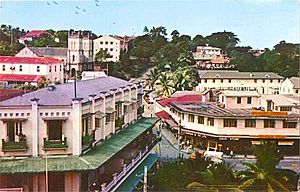

By the 1820s, traders returned for "beche-de-mer." Levuka became the first European-style town in Fiji, on Ovalau island. The market for "beche-de-mer" in China was very profitable. British and American traders set up places on different islands to prepare the product. Local Fijians were hired to collect, prepare, and pack the sea cucumbers, which were then shipped to Asia. A good shipment could make a dealer about $25,000 profit in half a year. Fijian workers were often given guns and ammunition for their work. By the late 1820s, most Fijian chiefs had muskets and were good at using them. Some chiefs soon felt confident enough to take more powerful weapons from Europeans by force.

Christian missionaries, like David Cargill, also arrived in the 1830s. They came from places like Tonga and Tahiti, where people had recently become Christian. By 1840, the European settlement at Levuka had about 40 houses. A former whaler, David Whippey, was a well-known resident. Converting Fijians to Christianity, and the arrival of European control, happened slowly. Captain Charles Wilkes of the United States Exploring Expedition saw this firsthand. Wilkes wrote that "all the chiefs seemed to look upon Christianity as a change in which they had much to lose and little to gain." But they listened to the missionaries because they "bring vessels to their place and give them opportunities of obtaining many desirable articles." Christian Fijians were pressured to cut their hair short, wear the sulu (a type of skirt) from Tonga, and change their marriage and funeral traditions. This forced cultural change was called lotu.

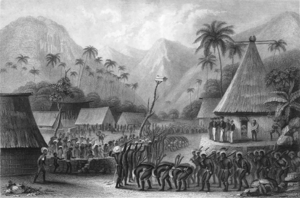

As Western powers demanded more from coastal Fijians, asking them to give up their culture, land, and resources, conflicts grew. In 1840, a group from the Charles Wilkes expedition had a fight with people from Malolo island. A lieutenant and a midshipman were killed. When Wilkes heard about the deaths, he organized a large attack on the Malolo people. He surrounded the island with his ships, burned all the Fijian boats he could find, and attacked the island. Most Maloloans hid in a strong village. They defended it with muskets and traditional weapons. Wilkes ordered his men to attack the village with rockets, which started fires. The village quickly became a huge fire, trapping the people inside. Wilkes himself wrote that the "shouts of men were intermingled with the cries and shrieks of the women and children" as they burned to death. Those who escaped the flames were shot by Wilkes' men. Wilkes then returned to his ship, waiting for the survivors to surrender. He said the remaining people should "sue for mercy" or "they must expect to be exterminated." About 57 to 87 Maloloan people were killed. Wilkes was investigated for these actions, but no punishment was given to him.

Cakobau and the Wars Against Christian Influence

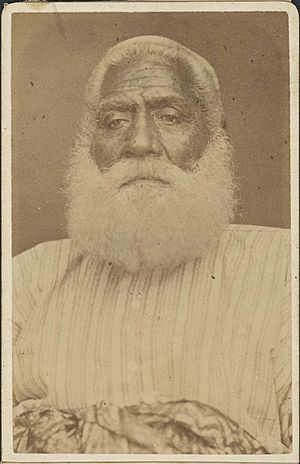

The 1840s were a time of fighting as different Fijian groups tried to become the most powerful. Eventually, a warlord named Seru Epenisa Cakobau from Bau Island became very influential. His father, Tanoa Visawaqa, was the Vunivalu (a chief title meaning 'Warlord' or 'Paramount Chief'). His father had already defeated a larger group and taken control of much of western Fiji. Cakobau became so powerful that he forced Europeans out of Levuka for five years. This happened because of a disagreement about them giving weapons to his local enemies. In the early 1850s, Cakobau went further and declared war on all Christians. His plans failed because missionaries in Fiji got help from the Tongans, who had already converted to Christianity. A British warship also arrived.

The Tongan Prince Enele Ma'afu, who was Christian, had settled on Lakeba Island in the Lau islands in 1848. He forced the local people to become Methodists. Cakobau and other chiefs in western Fiji saw Ma'afu as a threat to their power. They fought against his attempts to expand Tonga's control. However, Cakobau's power started to weaken. He demanded high taxes from other Fijian chiefs, who saw him as just one chief among equals. This caused many chiefs to leave his side.

Around this time, the United States also wanted to show its power in the region. They threatened to get involved after some problems with their consul in Fiji, John Brown Williams. In 1849, Williams' trading store was robbed after an accidental fire. In 1853, the European settlement of Levuka was burned down. Williams blamed Cakobau for both events. The US representative wanted Cakobau's capital at Bau destroyed in return. Instead, a naval blockade was set up around the island. This put more pressure on Cakobau to stop fighting foreigners and their Christian allies. Finally, on 30 April 1854, Cakobau gave up. He converted to Christianity. The traditional Fijian temples in Bau were destroyed, and sacred trees were cut down. Cakobau and his remaining men were then forced to join the Tongans, with American and British support. Together, they defeated the remaining chiefs in the region who still refused to convert. These chiefs were soon beaten. After these wars, most parts of Fiji, except for the inland highland areas, were forced to give up many of their old ways. They became controlled by Western interests. Cakobau remained as a symbol for the Fijian people and was allowed to use the title "Tui Viti" ("King of Fiji"). But the real power was now with foreign countries.

Attempts to Take Over Fiji

When John Williams' house on Nukulau Island was burned in 1855, the commander of a United States Navy ship demanded $5,000 from Cakobau as the "Tui Viti." More demands were added, totaling $38,531. Cakobau had to accept responsibility and promise to pay, or face punishment from the US Navy. He hoped that by delaying payment, the United States would reduce their demands.

However, reality caught up with Cakobau in 1858. A US Navy ship sailed into Levuka. Cakobau still couldn't pay his debt. He also faced more attacks on Viti Levu's south coast from Ma'afu and the Tongans. In the same year, William Pritchard, Britain's first official consul to Fiji, arrived. He wanted Britain to take over Fiji. Cakobau, in a difficult spot again, signed a document to give the islands to Britain. He understood that this would protect him from both the US demands and the Tongan attacks. The document was sent to London for official approval. Meanwhile, Pritchard set up the Great Council of Chiefs to get more support for British control. Pritchard also forced Ma'afu to officially give up Tonga's claims to the area. In 1862, after four years of thinking about it, the British government decided there was little benefit in ruling "yet another savage race." They chose not to approve the takeover. They thought Fiji was too far away and wouldn't make enough money for the Empire. They also believed Cakobau was just one chief among many and didn't have the power to give away the islands.

Cotton, Groups, and the Kai Colo

The price of cotton went up a lot during the American Civil War (1861–1865). This led to hundreds of settlers coming to Fiji in the 1860s from Australia and the United States. They wanted to get land and grow cotton. Since Fiji didn't have a strong government yet, these planters often got land through violence or trickery. They would exchange weapons with Fijians who might not even have been the real owners. This made land cheap to get, but it also caused problems between planters who claimed the same land. There was no unified government to solve these arguments. In 1865, the settlers suggested forming a group of the seven main native kingdoms in Fiji to create some kind of government. This worked at first, and Cakobau was chosen as the first president of this group. Cakobau and the other Fijian chiefs were mostly involved to make the government seem legitimate, but it was really a government for the white settlers. Cakobau was given a cheap crown to go with his self-declared title of Tui Viti.

With high demand for land, white planters started moving into the hilly interior of Viti Levu, Fiji's largest island. This led to direct conflict with the Kai Colo. This was a general name for the different Fijian groups living in these inland areas. The Kai Colo still lived a mostly traditional lifestyle. They were not Christian, and they were not under Cakobau's rule or the confederacy. In 1867, a missionary named Thomas Baker was killed by Kai Colo in the mountains. The acting British consul, John Bates Thurston, demanded that Cakobau lead a force of Fijians from coastal areas to defeat the Kai Colo. Cakobau eventually led a campaign into the mountains but suffered a humiliating loss. Sixty-one of his fighters were killed. In desperation, Cakobau suggested bringing in hired soldiers from Australia to get rid of the Kai Colo and take their land as payment. This plan was rejected. Cakobau not only lost his position as head of the confederacy, but the confederacy itself fell apart.

At this time, the Australia-based Polynesia Company wanted to buy land near what was then a Fijian village called Suva. In return for 5,000 square kilometers, the company agreed to pay Cakobau's old debt to the United States. In 1868, the company's settlers came to the 575 square kilometers of land. Other planters joined them, moving further up the Rewa River to set up their properties. These settlers quickly clashed with the local eastern Kai Colo people, known as the Wainimala. John Bates Thurston asked the British Royal Navy for help. The Navy sent Commander Rowley Lambert and a ship to punish the Wainimala. Lambert sent an armed force of 87 men, including marines and settlers, up the river. They bombed and burned the village of Deoka. A fight followed, resulting in two wounded and one killed among Lambert's force. The Wainimala later said they had 40 casualties. The expedition also caused some settlers along the river to leave, as the Wainimala attacked and burned their houses in revenge.

Kingdom of Fiji (1871–1874)

By the end of 1870, there were about 2,500 white settlers in Fiji. The need for a working government that protected both Fijians and foreigners became clear again. After the confederacy collapsed, Ma'afu had set up a stable government in the Lau Islands. This government gave good land leases to planters, and Lomaloma became an important trading center, competing with Levuka. The Tongans were becoming powerful again. Other foreign powers, like the United States and even Prussia, were also thinking about taking over Fiji. This situation was not good for many settlers, almost all of whom were British from Australia. Britain, however, still refused to take over the country. So, a compromise was needed.

In June 1871, George Austin Woods, a former Royal Navy officer, helped Cakobau and a group of settlers and chiefs form a government. This new government had a House of Representatives, a Legislative Committee, and a Privy Council. Cakobau was declared the monarch (Tui Viti) and the Kingdom of Fiji was created. Most Fijian chiefs agreed to join, and even Ma'afu recognized Cakobau and took part in the new government. The kingdom quickly set up tax, land court, and policing systems. It also created other necessary services like a postal service and official money. However, not everyone was happy with this new arrangement.

Many settlers had come from Australia, where dealing with native people often involved force. To them, the idea of living in a country where native people could govern and tax white people was ridiculous. As a result, several angry, racially motivated groups appeared, such as the British Subjects Mutual Protection Society. One group even called themselves the Ku Klux Klan, like the white supremacist group in America. Even the British consul in Fiji at the time, Edward Bernard March, sided with these groups against Cakobau's government. This was despite the fact that almost all the power in the government was held by white settlers. However, when respected people like Charles St Julian, Robert Sherson Swanston, and John Bates Thurston were appointed by Cakobau, the government gained some authority.

More Fighting with the Kai Colo

As more white settlers came to Fiji, the desire to get land also grew. Once again, this led to conflict with the Kai Colo in the interior of Viti Levu. In 1871, two settlers were killed near the Ba River. This caused a large group of about 400 armed people to form. This group included white farmers, imported laborers, and coastal Fijians. They fought a battle with the Kai Colo near Cubu village, and both sides had to retreat. The village was destroyed, and the Kai Colo, even with muskets, had many casualties. The Kai Colo responded by frequently raiding the settlements of whites and Christian Fijians throughout the Ba district. Similarly, in the east of the island, villages along the Rewa River were burned. A "great many" Kai Colo were shot by a group of settlers called the Rewa Rifles.

Although Cakobau's government didn't approve of settlers taking justice into their own hands, it did want the Kai Colo defeated and their land sold. The solution was to form an army. Robert S. Swanston, the minister for Native Affairs, organized the training and arming of Fijian volunteers and prisoners to become soldiers. This force was called the King's Troops or the Native Regiment. Two white settlers, James Harding and W. Fitzgerald, were put in charge of this group. Many white plantation owners didn't like this, as they didn't trust an army of Fijians to protect their interests.

The situation got worse in early 1873 when the Burns family was killed by a Kai Colo raid. Cakobau's government sent 50 King's Troopers to the area to restore order. The local white settlers, with their own large force, refused to cooperate. So, another 50 troops were sent to show the government's authority. To prove the Native Regiment's worth, this larger force went inland and killed about 170 Kai Colo people at Na Korowaiwai. When they returned to the coast, the white settlers still saw the government troops as a threat. A fight between the government's troops and the white settlers' group was only stopped by Captain William Cox Chapman of a British warship. He quickly arrested the white leaders, forcing their group to break up. The King's Troops and Cakobau's government now had complete power to defeat the Kai Colo.

From March to October 1873, about 200 King's Troops, along with around 1,000 coastal Fijian and white volunteer helpers, led a campaign through the highlands of Viti Levu to destroy the Kai Colo. Major Fitzgerald and Major H.C. Thurston (John Bates Thurston's brother) led attacks from two different directions. The combined forces of the Kai Colo clans made a stand at Na Culi village. The Kai Colo were defeated using dynamite and fire to force them out of their defensive positions in mountain caves. Many Kai Colo were killed. One of the main leaders, Ratu Dradra, was forced to surrender with about 2,000 men, women, and children. They were taken prisoner and sent to the coast. In the months after this defeat, the only main resistance came from the clans around Nibutautau village. Major H.C. Thurston crushed this resistance. Villages were burned, Kai Colo were killed, and many more prisoners were taken. The operations were now over. About 1,000 prisoners (men, women, and children) were sent to Levuka. Many were sold into slavery and forced to work on plantations throughout the islands.

Forced Labor and Slavery in Fiji

Before British Control (1865 to 1874)

The "blackbirding" era began in Fiji on 5 July 1865. This was when Ben Pease got the first license to bring 40 workers from the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) to Fiji. These workers were needed for cotton plantations. The American Civil War had stopped the supply of cotton to the world market, so growing cotton in Fiji could be very profitable. Thousands of American and Australian planters came to Fiji to set up plantations, and the demand for cheap labor grew quickly. Bringing workers from the Pacific Islands to Fiji continued until 1911, when it was made illegal. A total of about 45,000 Islanders were brought to work in Fiji during this 46-year period. About a quarter of them died while working.

In 1868, the British Consul in Fiji, John Bates Thurston, introduced minor rules for the trade. He started a system where labor ships needed a license. Melanesian workers were usually hired for three years, earning three pounds per year, plus basic clothes and food. This payment was half of what was offered in Queensland, Australia. Like Queensland, payment was only given at the end of the three-year term, usually in poor quality goods instead of cash. Most Melanesians were taken through a mix of trickery and violence. They were then locked in the ship's cargo hold to prevent escape. They were sold in Fiji to colonists for £3 to £6 for men and £10 to £20 for women. After the three-year contract ended, the government required captains to take the surviving workers back to their villages. However, many were dropped off at places far from their homes.

A well-known event in the blackbirding trade was the 1871 trip of the ship Carl. Dr. James Patrick Murray organized this trip to get workers for Fiji's plantations. Murray had his men turn their collars around and carry black books, to make them look like church missionaries. When islanders were invited to a religious service, Murray and his men would pull out guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the trip, Murray and his crew shot about 60 islanders. He was never put on trial for his actions, as he was given immunity for testifying against his crew members. The captain of the Carl, Joseph Armstrong, and the mate Charles Dowden, were sentenced to death, but this was later changed to life imprisonment.

Some Islanders brought to Fiji against their will tried desperately to escape. Some groups managed to overpower the crews of smaller ships. They would take control of these ships and try to sail back to their home islands. For example, in late 1871, Islanders on the Peri, who were being taken to a plantation, freed themselves. They killed most of the crew and took charge of the ship. Unfortunately, the ship had little food and was blown westward into the open ocean. They drifted for two months. Finally, the Peri was spotted by Captain John Moresby near Hinchinbrook Island off the coast of Queensland. Only thirteen of the original eighty kidnapped Islanders were alive and rescued.

After British Control (1875 to 1911)

The British took control of Fiji in October 1874, but the trade in Pacific Islanders for labor continued. In 1875, the year of a terrible measles outbreak, the chief medical officer in Fiji reported that 540 out of every 1,000 Islander laborers died. The Governor of Fiji, Sir Arthur Gordon, not only supported getting workers from the Pacific Islands but also actively helped plan to bring many more workers from India. The creation of the Western Pacific High Commission in 1877, based in Fiji, made the trade seem more official by extending British authority over most people in Melanesia.

Starting in 1879, with the arrival of the ship Leonidas, Indian workers began to arrive in Fiji. These workers were under a system where they had to work for a certain period. However, this Indian labor was more expensive. So, the market for blackbirded Islander workers remained strong for much of the 1880s. By 1890, fewer Melanesian laborers were brought in. Instead, more Indian workers were imported. But Islanders were still recruited and worked in places like sugar mills and ports. In 1901, Islanders were still being sold in Fiji for £15 each. It wasn't until 1902 that a system of paying monthly cash wages directly to the workers was suggested. When Islander laborers were sent away from Queensland in 1906, about 350 were moved to plantations in Fiji. After the recruitment system ended in 1911, those who stayed in Fiji settled in areas like Suva. Their mixed-heritage descendants see themselves as a distinct community. However, to outsiders, their language and culture are hard to tell apart from native Fijians.

Slavery of Fijians

Besides the forced labor from other Pacific islands, thousands of native Fijians were also sold into slavery on the plantations. As the Cakobau government (supported by white settlers) and later the British colonial government took control of more areas in Fiji, the prisoners of war were often sold at auction to planters. This not only brought money to the government but also spread out the rebels to different, often isolated islands where plantations were located. The land these people lived on before they became slaves was then also sold for more money. For example, the Lovoni people of Ovalau island, after being defeated in a war in 1871, were rounded up and sold to settlers for £6 each. Two thousand Lovoni men, women, and children were sold, and their slavery lasted five years. Similarly, after the Kai Colo wars in 1873, thousands of people from the hill tribes of Viti Levu were sent to Levuka and sold into slavery. Warnings from the British Royal Navy that buying these people was illegal were mostly ignored. The British consul in Fiji, Edward Bernard March, often pretended not to see this type of labor trade.

Fiji Becomes a British Colony

Britain Takes Control in 1874

Even though Cakobau's government won battles against the Kai Colo, it faced problems with its authority and money. Native Fijians and white settlers refused to pay taxes, and the price of cotton had dropped. With these big issues, John Bates Thurston asked the British government, on Cakobau's behalf, to take over the islands again. The new British government, led by Benjamin Disraeli, wanted to expand the empire. So, they were much more open to taking over Fiji than before.

The killing of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson in the Reef Islands had caused public anger. This was made worse by the massacre of over 150 Fijians on a ship called the Carl by its crew. Two British officials were sent to Fiji to look into the idea of taking over. The situation was complicated by power struggles between Cakobau and his old rival, Ma'afu. Both men changed their minds many times over several months. On 21 March 1874, Cakobau made a final offer, which the British accepted. On 23 September, Sir Hercules Robinson, who would soon become the British Governor of Fiji, arrived on a British warship. He greeted Cakobau with a royal 21-gun salute. After some hesitation, Cakobau agreed to give up his "Tui Viti" title, keeping the title of Vunivalu, or Protector. The official handover happened on 10 October 1874. On that day, Cakobau, Ma'afu, and some of the main Chiefs of Fiji signed two copies of the Deed of Cession. This is how the Colony of Fiji was started. British rule then lasted for 96 years.

The Measles Outbreak of 1875

To celebrate Fiji becoming a British colony, Hercules Robinson, who was the Governor of New South Wales at the time, took Cakobau and his two sons to Sydney. There was a measles outbreak in Sydney, and all three Fijians caught the disease. When they returned to Fiji, the colonial leaders decided not to quarantine the ship they were on. This was despite the British knowing a lot about how devastating infectious diseases could be to people who had never been exposed to them. In 1875–76, a measles outbreak caused by this decision killed over 40,000 Fijians, which was about one-third of the Fijian population. Some Fijians who survived believed that this failure to quarantine was a deliberate act to spread the disease. While there was no proof it was intentional, this decision, one of the first acts of British control in Fiji, was at the very least extremely careless.

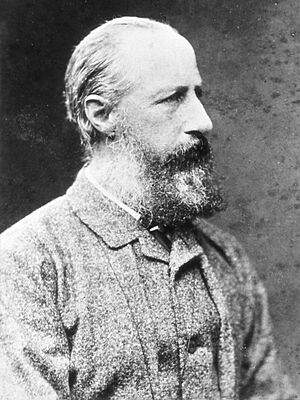

Sir Arthur Gordon and the "Little War"

Sir Hercules Robinson was replaced as Governor of Fiji in June 1875 by Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon. Gordon immediately faced a rebellion from the Qalimari and Kai Colo people. In early 1875, a colonial official had met with thousands of highland clansmen to make their submission to British rule and Christianity official. This meeting accidentally spread the measles epidemic to the highlanders, causing many deaths. As a result, anger at the British colonists grew, and a widespread uprising quickly began. Villages along the Sigatoka River and in the highlands refused British control. Gordon was given the task of stopping this rebellion.

In what Gordon called the "Little War," the rebellion was put down through two coordinated military campaigns in western Viti Levu. The first was led by Gordon's cousin against the Qalimari rebels along the Sigatoka River. The second campaign was led by Louis Knollys against the Kai Colo in the mountains north of the river. Governor Gordon put the area under a type of military rule, giving his relatives and Knollys complete power to carry out their missions without legal limits. The two rebel groups were kept separate by a force stationed at Nasaucoko. This force also made sure the rebellion didn't spread east. The war involved soldiers from Cakobau's old Native Regiment, supported by about 1,500 Christian Fijian volunteers from other areas. The New Zealand government provided most of the advanced weapons, including one hundred rifles.

The campaign along the Sigatoka River used a "scorched earth" policy. Many rebel villages were burned, and their fields were destroyed. After the main fortified towns were captured and destroyed, the Qalimari surrendered in large numbers. Those who weren't killed were taken prisoner and sent to the coastal town of Cuvu. This included 827 men, women, and children, as well as the rebel leader. The women and children were sent to places like Nadi. Of the men, 15 were sentenced to death in a quick trial. Fourteen were executed, and one prisoner escaped.

The northern campaign against the Kai Colo in the highlands was similar. It involved removing rebels from large, well-protected caves. Knollys managed to clear the caves "after some considerable time and large expenditure of ammunition." These caves held entire communities, so many men, women, and children were killed or wounded. The rest were taken prisoner and sent to towns on the northern coast.

By the end of October 1876, the "Little War" was over. Gordon had succeeded in defeating the rebels in Viti Levu's interior. Insurgents who weren't killed or executed were sent into exile with hard labor for up to 10 years. Some non-fighters were allowed to return and rebuild their villages, but Gordon ordered many highland areas to remain empty and in ruins. Gordon also built a military fort to maintain British control. He renamed the Native Regiment the Armed Native Constabulary to make it seem less like a military force.

To further control society throughout the colony, Governor Gordon created a system of appointed chiefs and village police officers in different districts. These officials would carry out his orders and report any disobedience. Gordon used the chief titles Roko and Buli for these deputies. He also established a Great Council of Chiefs that reported directly to him as the Supreme Chief. This group existed until it was stopped by the military-backed government in 2007 and officially ended in 2012. Gordon also took away Fijians' ability to own, buy, or sell land as individuals. Control of land was transferred to colonial authorities.

Indian Workers in Fiji

Gordon decided in 1878 to bring workers from India to work on the sugarcane fields that had replaced the cotton plantations. The first 463 Indians arrived on 14 May 1879. This was the start of about 61,000 workers who would come before the system ended in 1916. The plan was to bring Indian workers to Fiji on a five-year contract. After that, they could return to India at their own cost. If they chose to renew their contract for another five years, they could return to India at the government's expense or stay in Fiji. Most chose to stay.

Between 1879 and 1916, tens of thousands of Indians moved to Fiji to work as laborers, especially on sugarcane plantations. A total of 42 ships made 87 trips, carrying Indian workers to Fiji. Initially, ships brought laborers from Calcutta. But from 1903, most ships also brought laborers from Madras and Mumbai. A total of 60,965 passengers left India, but only 60,553 (including births at sea) arrived in Fiji. Sailing ships took about 73 days for the trip, while steamships took 30 days.

Workers who wanted to return to India had two choices. One was to pay for their own travel. The other was free travel, but with certain conditions. To get free passage back to India, workers had to be over twelve years old when they arrived. They also had to complete at least five years of service and live in Fiji for a total of ten years in a row. Children born to these workers in Fiji could go with their parents or guardians back to India if they were under twelve. Because it was expensive to return at their own cost, most workers returning to India left Fiji about ten to twelve years after arriving. The total number of people who returned under this system is recorded as 39,261. Since 60,553 arrived, many workers never returned to India.

The Tuka Rebellions

With British authorities controlling almost every part of native Fijian life, some inspiring individuals started speaking out. They preached about returning to pre-colonial culture and gained followers among those who felt powerless. These movements were called Tuka, which means "those who stand up." The first Tuka movement was led by Navosavakandua, meaning "he who speaks only once." He told his followers that if they returned to traditional ways and worshipped old gods, their current situation would change. The white people and their puppet Fijian chiefs would become subservient to them. Navosavakandua had been sent away from the Viti Levu highlands in 1878 for causing trouble. The British quickly arrested him and his followers after this open act of rebellion. He was exiled again, this time to Rotuma, where he died soon after his 10-year sentence ended.

However, other Tuka groups soon appeared. The British colonial government was harsh in stopping both the leaders and followers. Leaders were sent away, and in 1891, entire villages that supported the Tuka ideas were deported as punishment. Three years later, in the highlands of Vanua Levu, where locals had returned to traditional religion, the Governor of Fiji, John Bates Thurston, ordered the Armed Native Constabulary to destroy towns and religious items. Leaders were jailed, and villagers were exiled or forced to join government-controlled communities. Later, in 1914, Apolosi Nawai became a leader of Fijian Tuka resistance. He started a company that would legally control the farming industry and boycott European planters. The company was called the Viti Kabani, and it was very successful. The British and their Council of Chiefs could not stop the Viti Kabani's growth. Again, the colonists had to send in the Armed Native Constabulary. Apolosi and his followers were arrested in 1915, and the company collapsed in 1917. Over the next 30 years, Apolosi was arrested, jailed, and exiled many times. The British saw him as a threat until he died in 1946.

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR)

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company (Fiji) (CSR) started working in Fiji in 1880. Until it stopped operations in 1973, it had a big impact on Fiji's politics and economy. Before coming to Fiji, CSR had sugar refineries in Melbourne, Australia, and Auckland, New Zealand. They decided to start growing sugarcane and producing raw sugar to protect themselves from changes in the price of raw sugar. In May 1880, Fiji's Colonial Secretary John Bates Thurston convinced CSR to expand to Fiji. He made 2,000 acres (8 square kilometers) of land available for them to set up plantations.

Fiji in World War I

Fiji was only slightly involved in World War I. One interesting event happened in September 1917. A German count named Felix von Luckner arrived at Wakaya Island, off the eastern coast of Viti Levu. His ship had run aground in the Cook Islands after bombing a French territory. On 21 September, the local police inspector took some Fijians to Wakaya. Von Luckner, not knowing they were unarmed, surprisingly surrendered.

The British colonial leaders did not allow Fijians to join the army. They said they didn't want to take advantage of the Fijian people. However, one Fijian chief, a great-grandson of Cakobau, did join the French Foreign Legion. He received France's highest military award. After getting a law degree from Oxford University, this chief returned to Fiji in 1921. He was both a war hero and the country's first university graduate. In the years that followed, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, as he was later known, became the most powerful chief in Fiji. He helped create the early institutions for what would become modern Fiji.

Fiji in World War II

By World War II, the United Kingdom had changed its policy and allowed native people to join the army. Many thousands of Fijians volunteered for the Fiji Infantry Regiment. This regiment was led by Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, another great-grandson of Seru Epenisa Cakobau. The regiment fought alongside New Zealand and Australian army units during the war.

Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on 8 December 1941 (Fiji time) marked the start of the Pacific War. Japanese submarines sent planes to fly over Fiji. Because of its central location, Fiji was chosen as a training base for the Allies. An airstrip was built at Nadi (which later became an international airport), and gun positions were placed along the coast. Fijians became known for their bravery in the Solomon Islands. One war reporter described their ambush tactics as "death with velvet gloves." Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu was given the highest military award after his death for his bravery in a battle.

However, Indo-Fijians generally refused to join the army. They had asked for equal treatment to Europeans, but this was refused. They disbanded a group they had organized. They only contributed one officer and 70 enlisted men in a reserve transport section, on the condition that they would not be sent overseas. The refusal of Indo-Fijians to play an active role in the war efforts became a reason used by Fijian nationalists to explain tensions between ethnic groups after the war.

Developing Political Systems

A Legislative Council, which gave advice, had existed since 1874. But in 1904, it became partly elected. European men could elect 6 of the 19 Council members. Two members were chosen by the Governor from a list of 6 candidates given by the Great Council of Chiefs. Another 8 "official" members were chosen by the Governor himself. The Governor was the 19th member. The first Indian member was appointed in 1916. This position became elected from 1929. An Executive Council was also set up in 1904. This was not like a modern government cabinet, as its members were not responsible to the Legislative Council. Fiji made its first coins in 1934. Before this, British money was used.

After World War II, Fiji started taking steps towards governing itself. The Legislative Council was expanded to 32 members in 1953. Fifteen of these were elected and divided equally among the three main ethnic groups: native Fijians, Indo-Fijians, and Europeans. Indo-Fijian and European voters directly elected 3 of their 5 members (the other two were appointed by the Governor). The 5 native Fijian members were all chosen by the Great Council of Chiefs. Ratu Sukuna was chosen as the first Speaker. Even though the Legislative Council still had few powers compared to a modern Parliament, it brought native Fijians and Indo-Fijians into the official political structure for the first time. This helped start a modern political culture in Fiji.

These steps towards self-rule were welcomed by the Indo-Fijian community. By this time, they had more people than the native Fijian population. Many Fijian chiefs feared Indo-Fijian control. They preferred the kind rule of the British over Indo-Fijian leadership. So, they resisted British moves towards self-government. However, by this time, the United Kingdom had decided to give up its colonies. So, they pushed ahead with reforms. All Fijian people could vote for the first time in 1963. The legislature became fully elected, except for 2 members out of 36 chosen by the Great Council of Chiefs. In 1964, the first step towards responsible government happened. Specific areas of responsibility were given to certain elected members of the Legislative Council. They were officially advisers to the colonial Governor, not ministers with real power. But over the next three years, the Governor treated these members more and more like ministers. This was to prepare them for responsible government.

Responsible Government

A meeting was held in London in July 1965 to discuss changes to the government, aiming for responsible government. Indo-Fijians, led by A. D. Patel, demanded full self-government right away. They wanted a fully elected legislature, chosen by everyone voting together. The ethnic Fijian group strongly rejected these demands. They still feared losing control over their land and resources if an Indo-Fijian government came to power. However, the British made it clear they were determined to bring Fiji to self-government and eventually independence. Realizing they had no choice, Fiji's chiefs decided to negotiate for the best deal they could get.

A series of compromises led to a cabinet system of government in 1967. Ratu Kamisese Mara became the first Chief Minister. Talks between Mara and Sidiq Koya, who took over leadership of the mainly Indo-Fijian National Federation Party in 1969, led to another meeting in London in April 1970. At this meeting, Fiji's Legislative Council agreed on a compromise for elections and a timeline for independence. The Legislative Council would be replaced by a two-house Parliament. One house, the Senate, would be mostly made up of Fijian chiefs. The other, the House of Representatives, would be elected by the people. In the 52-member House, native Fijians and Indo-Fijians would each get 22 seats. Twelve of these would be for voters registered by their ethnic group. Another 10 would be for members chosen by ethnicity but elected by everyone. Eight more seats were for "General electors" – Europeans, Chinese, and other minorities. With this compromise, Fiji became independent on 10 October 1970.

Queen Elizabeth II visited Fiji before its independence in 1953, 1963, and March 1970. She also visited after independence in 1973, 1977, and 1982.

Independent Fiji

Fiji as a Commonwealth Realm

In April 1970, a meeting in London agreed that Fiji should become a fully independent nation within the Commonwealth of Nations. Fiji became an independent country on 10 October of that year.

One of the main issues in Fijian politics has been land ownership. Native Fijian communities feel very strongly connected to their land. In 1909, around the time many Indian workers were arriving, land ownership rules were set. No more land could be sold. Today, over 80% of the land is owned by native Fijians, collectively by traditional Fijian clans. Indo-Fijians grow over 90% of the sugar crop. But they must lease the land from its ethnic Fijian owners instead of buying it. Leases have generally been for 10 years, usually renewed for two more 10-year periods. Many Indo-Fijians argue these terms don't give them enough security. They have pushed for 30-year leases that can be renewed. However, many ethnic Fijians fear that an Indo-Fijian government would reduce their control over the land.

The main group of voters for Indo-Fijian parties are sugarcane farmers. The farmers' main way to influence things has been their ability to organize widespread boycotts of the sugar industry. This can severely damage the economy.

After independence, politics were mostly controlled by Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and the Alliance Party. This party had the support of traditional Fijian chiefs, leading Europeans, and some Indo-Fijians. The main opposition party, the National Federation Party, mostly represented rural Indo-Fijians. Relations between the different groups were managed without serious conflict. A short political crisis happened after the March 1977 election. The Indian-led National Federation Party (NFP) won a small majority of seats. But they couldn't form a government because of internal leadership problems. Also, some members worried that native Fijians would not accept Indo-Fijian leadership. The NFP split apart three days after the election. In a controversial move, the Governor-General asked the defeated Mara to form a temporary government. This was until a second election could solve the problem. This election was held in September that year. Mara's Alliance Party won with a record majority of 36 seats out of 52. The Alliance Party's majority was smaller in the 1982 election, but Mara kept power with 28 seats out of 52. Mara suggested a "government of national unity" – a big partnership between his Alliance Party and the NFP. But the NFP leader rejected this.

The 1987 Coups

Democratic rule was stopped by two military takeovers in 1987. These happened because people increasingly felt that the government was controlled by the Indo-Fijian (Indian) community. The second coup in 1987 led to the Fijian monarchy and the Governor General being replaced by a non-executive president. The country's name was changed from Fiji to Republic of Fiji and then in 1997 to Republic of the Fiji Islands. The two coups and the related unrest caused many Indo-Fijians to leave the country. This loss of people led to economic problems and made sure that Melanesians became the majority.

In April 1987, a group led by Timoci Bavadra, an ethnic Fijian who was mostly supported by the Indo-Fijian community, won the election. They formed Fiji's first government with an Indian majority, and Bavadra became Prime Minister. After less than a month, on 14 May 1987, Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka (who had worked with United Nations peacekeeping forces) forcibly removed Bavadra from power.

At first, Rabuka said he was loyal to Queen Elizabeth II. However, the Governor-General, Penaia Ganilau, tried to protect Fiji's constitution. He refused to officially approve the new government that Rabuka had set up. After a period of talks, Rabuka staged a second coup on 25 September 1987. The military government cancelled the constitution and declared Fiji a republic on 10 October. This was the seventeenth anniversary of Fiji's independence from the United Kingdom. This action, along with protests from the Indian government, led to Fiji being removed from the Commonwealth. Foreign governments, including Australia and New Zealand, did not officially recognize Rabuka's government. On 6 December, Rabuka resigned as Head of State. The former Governor-General, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, was appointed the first President of the Fijian Republic. Mara was made Prime Minister again, and Rabuka became Minister of Home Affairs.

The 1990 Constitution

In 1990, a new Constitution was put in place. It gave ethnic Fijians more power in the political system. A group called GARD (Group Against Racial Discrimination) was formed to oppose this constitution and bring back the 1970 constitution. In 1992, Sitiveni Rabuka, the military leader who had carried out the 1987 coup, became Prime Minister after elections held under the new constitution. Three years later, Rabuka set up a group to review the Constitution. In 1997, this group wrote a new constitution that most leaders from both the native Fijian and Indo-Fijian communities supported. Fiji was then allowed back into the Commonwealth of Nations.

The new government wrote a new Constitution that started in July 1990. Under its rules, ethnic Fijians were guaranteed majorities in both houses of the legislature. Before this, in 1989, the government had shown statistics that for the first time since 1946, ethnic Fijians were the majority of the population. More than 12,000 Indo-Fijians and other minorities had left the country in the two years after the 1987 coups. After leaving the military, Rabuka became Prime Minister under the new constitution in 1992.

Tensions between ethnic groups continued in 1995–1996. This was over the renewal of land leases for Indo-Fijians and political moves around the required 7-year review of the 1990 constitution. The Constitutional Review Commission created a draft constitution. This draft slightly increased the size of the legislature. It lowered the number of seats reserved for each ethnic group. It also reserved the presidency for ethnic Fijians but allowed the position of Prime Minister to be held by people of all races. Prime Minister Rabuka and President Mara supported the proposal, but nationalist native Fijian parties opposed it. The reformed constitution was approved in July 1997. Fiji was allowed back into the Commonwealth in October.

The first elections under the new 1997 Constitution happened in May 1999. Rabuka's group was defeated by an alliance of Indo-Fijian parties led by Mahendra Chaudhry. He became Fiji's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister.

The 2000 Coup and Qarase Government

The year 2000 brought another military takeover. This was started by George Speight. It effectively removed the government of Mahendra Chaudhry, who had become the country's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister in 1997. Commodore Frank Bainimarama took control after President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara resigned, possibly under force. Later in 2000, Fiji experienced two mutinies. Rebel soldiers went on a rampage at a military barracks in Suva. The High Court ordered the constitution to be put back in place. In September 2001, to bring back democracy, a general election was held. It was won by interim Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase's party.

Chaudhry's government lasted only a short time. After barely a year in office, Chaudhry and most other members of parliament were taken hostage in the House of Representatives by armed men led by ethnic Fijian nationalist George Speight, on 19 May 2000. The situation lasted for eight weeks. During this time, Chaudhry was removed from office by the then-President because he couldn't govern. The Fijian military then took power and helped negotiate an end to the situation. They then arrested Speight when he broke the agreement. Former banker Laisenia Qarase was named interim Prime Minister and head of the temporary civilian government by the military and the Great Council of Chiefs in July. A court order restored the constitution early in 2001. A later election confirmed Qarase as Prime Minister.

In 2005, Qarase's government suggested a Reconciliation and Unity Commission. This commission would have the power to recommend payments for victims of the 2000 coup and forgiveness for those who carried it out. However, the military, especially its top commander, Frank Bainimarama, strongly opposed this bill. Bainimarama agreed with critics who said that giving forgiveness to supporters of the current government who were involved in the violent coup was a trick. His strong criticism of the law continued for months. This made his already tense relationship with the government even worse.

The 2006 Coup

In late 2006, Bainimarama played a key role in another military takeover. Bainimarama gave Prime Minister Qarase a list of demands. This happened after a bill was proposed in parliament that would have offered pardons to people involved in the 2000 coup attempt. He gave Qarase a deadline of 4 December to agree to these demands or resign. Qarase firmly refused to give in or resign. On 5 December, the president, Ratu Josefa Iloilo, was said to have signed a legal order dissolving the parliament after meeting with Bainimarama.

Unhappy with two bills in the Fijian Parliament, one of which offered forgiveness for the leaders of the 2000 coup, military leader Commodore Frank Bainimarama asked Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase to resign in mid-October 2006. The Prime Minister tried to fire Bainimarama, but he was unsuccessful. The Australian and New Zealand governments expressed worries about a possible coup. On 4 November 2006, Qarase removed the controversial forgiveness parts from the bill.

On 29 November, New Zealand's foreign Minister organized talks in Wellington between Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase and Commodore Bainimarama. The minister reported the talks as "positive." But after returning to Fiji, Commodore Bainimarama announced that the military would take control of most of Suva and fire into the harbor. Bainimarama announced on 3 December 2006 that he had taken control of Fiji.

Bainimarama gave the presidency back to Ratu Josefa Iloilo on 4 January 2007. In return, Iloilo formally appointed Bainimarama as interim Prime Minister the next day.

In April 2009, the Fiji Court of Appeal ruled that the 2006 coup had been illegal. This started a political crisis. President Iloilo cancelled the constitution. He removed all government officials, including all judges and the head of the Central Bank. He then reappointed Bainimarama as interim Prime Minister under his "New Order." He also put in place a "Public Emergency Regulation" that limited travel within the country and allowed censorship of the press.

On 10 April 2009, Fijian President Ratu Josefa Iloilo announced on national radio that he had cancelled the Constitution of Fiji. He dismissed the Court of Appeal and all other parts of the justice system. He took all governing power in the country after the court ruled that the current government was illegal. The next day, he put Bainimarama back in charge. Bainimarama announced that there would be no elections until 2014.

A new Constitution was put into effect by the government in September 2013. A general election was held in September 2014. It was won by Bainimarama's FijiFirst Party. Having more than one citizenship, which was not allowed under the 1997 constitution, has been permitted since April 2009. It was made a right under the September 2013 Constitution.

As suggested in the 2008 People's Charter, a law in 2010 changed the word Fijian or indigenous Fijian to iTaukei in all written laws and official documents when talking about the original native settlers of Fiji. All citizens of Fiji are now called Fijians.

Since 2014

On 14 March 2014, the Commonwealth group voted to change Fiji's full suspension from the Commonwealth to a suspension from its councils. This allowed Fiji to take part in some Commonwealth activities, including the 2014 Commonwealth Games. The suspension was lifted in September 2014.

The FijiFirst party, led by Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, won a clear majority in the country's 51-seat parliament in both the 2014 and the close 2018 elections.

In October 2021, Wiliame Katonivere was elected the new President of Fiji by the parliament.

On 24 December 2022, Sitiveni Rabuka, the head of the People's Alliance (PAP), became Fiji's 12th prime minister. He took over from Bainimarama after the December 2022 general election.

Role of the Military

For a country its size, Fiji has a fairly large military. It has sent many soldiers to UN peacekeeping missions around the world. Also, a significant number of former military personnel have worked in security jobs in Iraq after the 2003 invasion.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Fiyi para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Fiyi para niños

- Timeline of Fijian history

- Politics of Fiji

|

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |