History of Laos facts for kids

The land that is now Laos has been home to people for a very long time, even since the Stone Age. The first people to live in the highlands of Laos were likely Australo-Melanesians, who were part of the Hoabinhian culture. Later, other groups like the Austroasiatic and Austronesian people arrived. Over time, Laos was also influenced by cultures from China and India.

Laos as we know it today comes from the ancient Lao kingdom of Lan Xang. This kingdom was united from 1357 to 1707. After that, it split into three smaller kingdoms: Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and Champasak. From 1779 to 1893, these kingdoms were under the control of Siam (modern Thailand). In 1893, France took over and reunited the area under the French Protectorate of Laos. The borders of modern Laos were set by the French. Laos finally became an independent country in 1953, after being part of the French Colonial Empire.

Contents

Studying Laos's Past

It has been hard to study the ancient history of Laos. The land is very rugged, and there are still many unexploded bombs left from wars in the 20th century. Also, local people and the government have sometimes been sensitive about historical research.

French explorers first started archaeological digs in Laos. But serious work only really began in the 1990s after the Lao Civil War. Since 2005, a project called The Middle Mekong Archaeological Project (MMAP) has been digging and exploring sites along the Mekong River and its smaller rivers near Luang Prabang. They want to learn about the first human settlements in these river valleys.

Ancient Times

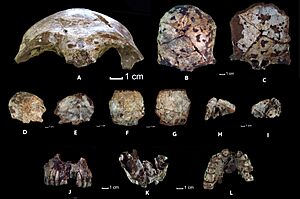

People who looked like modern humans moved into Southeast Asia over 50,000 years ago. We know this from old human bones found in the region. Some discoveries, like the fossils from the Tam Pa Ling Cave in Laos, suggest that these early humans might have mixed with older human groups like Homo erectus. The Tam Pa Ling fossil is between 46,000 and 63,000 years old, making it the oldest modern human fossil found in this area.

New research also shows that early humans moved in waves. They followed coastlines from west to east, but also used river valleys further inland, which was not thought before.

An early culture called the Hoabinhian appeared around 10,000 years ago. This culture is known for its stone tools and artifacts found in caves and rock shelters, first discovered in Vietnam and later in Laos.

First Farmers and Bronze Tools

The first people in Laos were the Australo-Melanesians. Later, people who spoke Austro-Asiatic languages arrived. These early groups contributed to the genes of the "Lao Theung" people, who live in the uplands of Laos today. The largest groups are the Khamu in the north and the Brao and Katang in the south.

Around 2,000 BC, people started farming wet rice and millet. These farming methods came from the Yangtze River valley in southern China. However, hunting and gathering food remained important, especially in the forests and mountains. The earliest known copper and bronze tools in Southeast Asia were found in Thailand and Vietnam, also around 2000 BCE.

The Mysterious Plain of Jars

From about 800 BCE to 200 CE, a trading society lived on the Xiangkhouang Plateau. They created a mysterious place called the Plain of Jars. This site has huge stone jars, some over 3 meters (10 feet) tall! It was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992. Workers are still clearing unexploded bombs from the area.

These jars are like stone coffins from the early Iron Age. They contain human remains, burial items, and pottery. Some sites have more than 250 jars. We don't know much about the people who made them. But the jars and the iron ore in the area suggest that these people were involved in profitable trade over land.

Early Kingdoms Influenced by India

Funan Kingdom

The first local kingdom in Indochina was called Kingdom of Funan by Chinese historians. It covered parts of modern Cambodia, southern Vietnam, and southern Thailand, starting around the 1st century CE. Funan was an "Indianised" kingdom, meaning it adopted many ideas from India. These included parts of their religion, government, writing, and architecture. Funan was also involved in profitable trade across the Indian Ocean.

Champa Kingdom

By the 2nd century CE, people from Austronesia had set up an Indian-influenced kingdom called Champa in what is now central Vietnam. The Cham people also made early settlements near modern Champasak in Laos. Funan grew and took over the Champasak region by the 6th century CE. Then, a new kingdom called Chenla replaced Funan. Chenla controlled large parts of modern Laos and was the first kingdom on Laotian soil.

Chenla Kingdom

The early capital of Chenla was Shrestapura, located near Champasak and the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Wat Phu. Wat Phu is a huge temple complex in southern Laos. It mixes natural surroundings with beautiful sandstone buildings. The Chenla people maintained and decorated these structures until 900 CE. Later, the Khmer people rediscovered and added to them in the 10th century.

By the 8th century CE, Chenla had split into "Land Chenla" (in Laos) and "Water Chenla" (in Cambodia). Land Chenla was known to the Chinese as "Po Lou" or "Wen Dan" and sent a trade group to the Tang dynasty in 717 CE. Water Chenla faced many attacks from other kingdoms and pirates. From this unstable time, the Khmer Empire grew.

Dvaravati City-States

In what is now northern and central Laos and northeast Thailand, the Mon people created their own kingdoms in the 8th century CE. These were outside the reach of the Chenla kingdoms. By the 6th century, Mon people in the Chao Phraya River Valley had formed the Dvaravati kingdoms. In the north, Haripunjaya became a strong rival. By the 8th century, the Mon had moved north and created city-states called "muang." These included Fa Daet (northeast Thailand), Sri Gotapura (near modern Tha Khek, Laos), Muang Sua (Luang Prabang), and Chantaburi (Vientiane).

Sri Gotapura was the strongest of these early city-states in the 8th century. It controlled trade throughout the middle Mekong region. These city-states were not strongly united politically, but they shared a similar culture. They also brought Therevada Buddhism from Sri Lankan missionaries to the region.

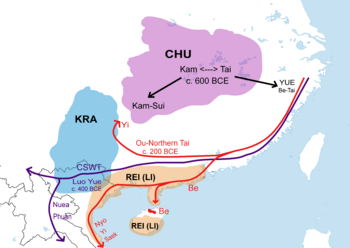

Tai People Move South

The Tai peoples, which include the Lao, have many theories about where they came from. Chinese records from the Han dynasty mention Tai-Kadai speaking people living in areas of modern Yunnan, China, and Guangxi.

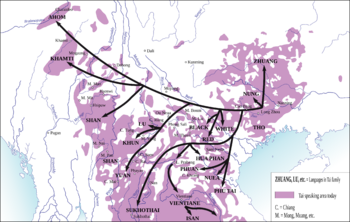

One idea suggests that the Tai-Kadai language family started around 1200 BCE in the middle Yangtze basin in China. Later, Tai people from Guangxi and northern Vietnam began moving south and west in the first 1,000 years CE. They eventually spread across all of mainland Southeast Asia. This movement might have been caused by China expanding and putting pressure on them.

Chinese historical texts record many revolts by "Lao" people in China. For example, in 722, 400,000 'Lao' rebelled. After the revolt, about 60,000 were killed. In 726, after another rebellion, over 30,000 rebels were captured and killed. These bloody events over three centuries likely caused many Tai people to move southwest. A 2016 study of genes in Thai and Lao people supports the idea that both groups came from the Tai–Kadai language family.

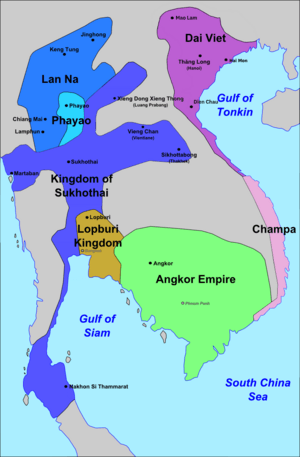

Once in Southeast Asia, the Tai people were influenced by the Khmer, the Mon, and especially by Buddhist India. The Tai kingdom of Lanna was founded in 1259 in northern Thailand. The Sukhothai Kingdom was founded in 1279 in Thailand and expanded eastward to take the city of Chantaburi (modern Vientiane) and northward to Muang Sua (modern Luang Prabang). The Tai people had firmly taken control of areas northeast of the declining Khmer Empire.

After the Sukhothai king died, Vientiane and Luang Prabang became independent city-states. This lasted until the kingdom of Lan Xang was founded in 1354.

The Legend of Khun Borom

The stories of the Tai people moving into Laos were kept alive through myths and legends. The Nithan Khun Borom, or "Story of Khun Borom", tells the origin story of the Lao people. It describes how Khun Borom's seven sons founded the Tai kingdoms of Southeast Asia. These myths also recorded Khun Borom's laws, which formed the basis of common law and identity for the Lao.

Among the Khamu people, the epic story of their hero Thao Hung, called Thao Hung Thao Cheuang, tells about the struggles of the local people when the Tai people arrived. Later, the Lao themselves wrote down this legend. It became an important literary treasure of Laos and one of the few stories that show life in Southeast Asia before Buddhism and Tai culture became widespread.

Lan Xang (1353–1707)

Lan Xang (1353–1707) was one of the largest kingdoms in Southeast Asia. Its name, "Land of a million elephants under the white parasol," showed the king's power and the kingdom's strong army. Fa Ngum founded Lan Xang in 1353 after many conquests. From 1353 to 1560, the capital was Luang Prabang.

Under different kings, the kingdom grew to include all of modern Laos, parts of Vietnam, southern China, Thailand, and northern Cambodia. Lan Xang was an independent kingdom for over 350 years. The first major foreign attack came from the Dai Viet in 1479, but they were defeated, though Luang Prabang was badly damaged.

The first half of the 16th century was a time of recovery and growth for Lan Xang. In the 1540s, problems in the neighboring Kingdom of Lanna led to rivalries between Burma, Ayutthaya, and Lan Xang. Lan Xang defeated an attack from Ayutthaya in 1540. Lan Xang then allied with Lanna to defend against attacks from Burma and Ayutthaya. In 1547, Lan Xang and Lanna were briefly united under Photisarath of Lan Xang and his son Setthathirath. Setthathirath later became one of Lan Xang's greatest kings.

The Burmese Toungoo dynasty began expanding in the late 1550s under King Bayinnaung. To better defend against Burma and manage the kingdom, Setthathirath moved the capital from Luang Prabang to Vientiane in 1560. Bayinnaung conquered Lanna and destroyed Ayutthaya in 1564. King Setthathirath fought two successful guerrilla wars against the Burmese. Lan Xang was the only independent Tai kingdom until his death in 1572. The Burmese finally conquered Lan Xang around 1573, making it a vassal state until 1591, when Setthathirath's son, Nokeo Koumane, regained independence.

Lan Xang recovered and became very powerful in the 17th century under King Sourigna Vongsa. He ruled for the longest time (1637–1694) and was known as a fair and strong ruler. In the 1640s, the first European explorers arrived, hoping to trade and convert people to Christianity. They were mostly unsuccessful, but they reported on Vientiane's wealth and impressive religious buildings. After Sourigna Vongsa died, arguments over who would rule, along with interference from Ayutthaya and Dai Viet, caused Lan Xang to split into smaller kingdoms in 1707.

Separate Kingdoms (1707–1779)

In 1707, the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang broke apart into three regional kingdoms: Vientiane, Luang Prabang, and later Champasak (1713). Vientiane was the strongest of the three. It controlled the Khorat Plateau (now part of Thailand) and fought with Luang Prabang for control of the Xieng Khouang Plateau.

The Kingdom of Luang Prabang was the first to form in 1707. The King of Lan Xang, Xai Ong Hue, was challenged by Kingkitsarat, a grandson of Sourigna Vongsa. Xai Ong Hue got help from the Vietnamese Emperor in exchange for recognizing Vietnam's power over Lan Xang. Kingkitsarat then rebelled, and an army from Ayutthaya helped divide the land between Luang Prabang and Vientiane.

In 1713, the southern Lao nobles continued to rebel, and the Kingdom of Champasak was formed. Champasak controlled the area south of the Xe Bang River and parts of the Khorat Plateau. Even though it had fewer people than Luang Prabang or Vientiane, Champasak was important for regional power and trade along the Mekong River.

In the 1760s and 1770s, Siam and Burma fought fiercely. They tried to make alliances with the Lao kingdoms to gain strength and prevent their enemy from doing so. This led to more conflict between Luang Prabang and Vientiane, as they often supported opposing sides in the Siam-Burma wars.

Siam's Influence (1779–1893)

By 1779, General Taksin of Siam had driven the Burmese out of Siam. He then conquered the Lao Kingdoms of Champasak and Vientiane. Luang Prabang had helped Siam and was forced to accept Siam's rule.

In Southeast Asia, kingdoms often followed a "Mandala" model. This meant that wars were fought to gain control of people for labor, control trade, and show religious power by taking important Buddhist symbols. To show his power, General Taksin took the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang statues from Vientiane. He also demanded that the Lao kings and their families promise loyalty to Siam. Under this system, vassal kings could still collect taxes, punish their own people, and appoint officials. Only major decisions like war and succession needed Siam's approval. Vassals also had to send yearly gifts and provide labor for state projects.

However, by 1782, Taksin was removed from power, and Rama I became king of Siam. He started changes that altered the traditional Mandala system. Many changes were made to control the Khorat Plateau (or Isan) more closely, which was culturally part of the Lao kingdoms. By 1826, the number of towns in Isan paying tribute directly to Bangkok had grown significantly. Siam forced people from Lao areas to move and work on projects, and increased taxes. This helped Siam rebuild after wars and grow its sea trade.

Siribunnyasan, the last independent king of Vientiane, died by 1780. His sons, Nanthasen, Inthavong, and Anouvong, were taken as prisoners to Bangkok. They later became kings of Vientiane under Siamese rule. Nanthasen was allowed to return to Vientiane with the Phra Bang statue, but the Emerald Buddha stayed in Bangkok, becoming a symbol of Lao captivity.

King Anouvong and Lao Pride

Anouvong is a very important and debated figure in Lao history. His short rebellion against Siam from 1826 to 1829 failed and led to the complete destruction of Vientiane. However, for the Lao people, he remains a strong symbol of defiance and national identity.

Thai and Vietnamese stories say Anouvong rebelled because he felt insulted at the funeral of Rama II in Bangkok. But the rebellion lasted three years and involved the whole Khorat Plateau for more complex reasons. Siam had forced many Lao people to move, taken their national symbols, and imposed heavy taxes. In 1812, Siam also blocked Lao trade along the Mekong River.

In 1819, a rebellion in Champasak gave Anouvong an opportunity. He sent his son Nyo to stop it, and in return, Anouvong's son was crowned king of Champasak. Anouvong's influence grew across Vientiane, Isan, Xieng Khouang, and Champasak.

When Rama III became king of Siam, he ordered a census of all people on the Khorat Plateau. This involved tattooing each villager with a number and their village name. This policy aimed to control Lao areas more strictly from Bangkok. People were very angry about the forced tattooing and higher taxes, which became a reason for the rebellion.

In late 1826, Anouvong prepared for war. His goals were to bring all ethnic Lao living in Siam back to the east bank of the Mekong, unite Lao power by allying with Chiang Mai and Luang Prabang, and get international support. In January, the fighting began. Lao armies captured several towns. Anouvong's forces pushed south to free Lao people who had been moved to Saraburi.

However, Anouvong underestimated Siam's military strength. Siam had new weapons from Europe. The Lao defense at Nong Bua Lamphu failed, and Siam destroyed the city. The Siamese then took Vientiane, and Anouvong fled. By 1828, Anouvong was captured and sent to Bangkok, where he died. Rama III ordered Vientiane to be completely destroyed and its people moved to the Isan region.

After the Rebellion and Vietnamese Involvement

After Vientiane was destroyed, Siam and Vietnam often disagreed over control of the Indochinese Peninsula. In 1831, Emperor Minh Mang of Vietnam sent troops to take Xieng Khouang. Siam and Vietnam fought several wars over Xieng Khouang and Cambodia.

Siam divided the Lao lands into three areas. In the north, Luang Prabang was controlled by its king and a small Siamese army. The central region was managed from Nong Khai, and the southern regions from Champasak. From the 1830s to the 1860s, small rebellions happened across Lao lands, but they were not as big or organized as Anouvong's rebellion. After each rebellion, Siamese troops would return to their centers, preventing any Lao region from building up a strong force.

Moving People and Slavery

Siam began moving ethnic Lao people in 1779. Skilled workers and court members were forced to move near Bangkok. Thousands of farmers were sent to other parts of Siam. However, huge forced movements of people, estimated between 100,000 and 300,000, began after King Anouvong's defeat in 1828 and continued until the 1870s. Most of these people were settled in the Isan region and were treated as "war slaves" or servants for the Thai elite. This changed the population and culture of Thailand and Laos. Today, there are five times more ethnic Lao people living on the west side of the Mekong (in Thailand) than on the east side (in Laos).

Slavery existed in Lao areas before 1828. But after the defeat and removal of most ethnic Lao, the remaining people on the east side of the Mekong were vulnerable. Lao Theung hill tribes, who had little to do with the rebellion, suffered the most from organized slave raids into Laos. They were often called kha or "slaves" by Thai and Lao people. Lao Theung were hunted or sold into slavery by raiding parties from Vietnam, Cambodia, Siam, Laos, and China. Even larger Lao Theung tribes would raid weaker ones. These raids continued throughout the 19th century.

Forced population transfers and slave raids decreased towards the end of the 19th century. This was because European observers and anti-slavery groups made it harder for the Bangkok elite to continue these practices. In 1880, slave raiding and trading became illegal, though debt slavery continued until 1905. The French later used the existence of slavery in Siam as a reason to establish a Protectorate of Laos in the 1880s and 1890s.

Haw Wars

In the 1840s, rebellions, slave raids, and people moving around made parts of what would become modern Laos very weak. In China, the Qing dynasty was trying to control hill peoples. This led to many refugees and rebel groups from the Taiping Rebellion moving into Lao lands. These rebel groups were known by their banners, like the Yellow Flags, Red Flags, and Black Flags. These groups caused a lot of trouble in the countryside, and Siam did little to stop them.

During the early and mid-19th century, the first Lao Sung groups, including the Hmong, Mien, and Yao, began settling in the higher areas of Phongsali province and northeast Laos. This movement of people was made easier by the political weakness that also allowed the Haw bandits to operate.

By the 1860s, the first French explorers were mapping the Mekong River, hoping to find a way to southern China. One of these explorers, Francis Garnier, was killed by Haw rebels. The French then fought many military campaigns against the Haw in Laos and Vietnam until the 1880s.

Colonial Period

How France Took Control of Laos

France became interested in Laos through the explorations of Doudart de Lagree and Francis Garnier in the 1860s. France hoped to use the Mekong River as a trade route to southern China. Even though the Mekong has many rapids and isn't fully navigable, the French hoped to make it work with engineering and railways. In 1886, Britain gained influence in northern Siam. To counter this, France sent Auguste Pavie to Luang Prabang to protect French interests.

Pavie arrived in Luang Prabang in 1887 just as Chinese and Tai bandits were attacking the city. They wanted to free their leader's brothers, who were held by the Siamese. Pavie helped the sick King Oun Kham escape the burning city to safety. This act earned the king's thanks and showed how weak the Siamese were in Laos. It also gave France a chance to gain control of the Sipsong Chu Thai region.

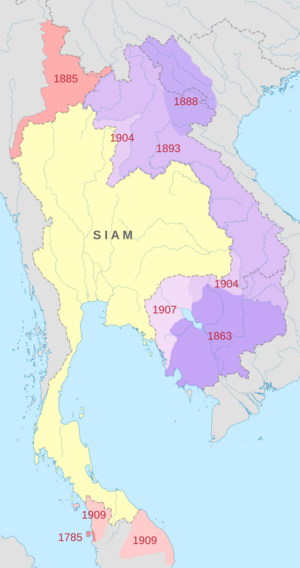

In 1892, Pavie became the French representative in Bangkok. He pushed for a French policy that ignored Siam's control over Lao lands on the east bank of the Mekong. He also highlighted Siam's practice of slavery and forced population transfers. Siam reacted by limiting French trade. By 1893, this led to military actions and "gunboat diplomacy." French and Siamese troops faced off, leading to the Paknam Incident on July 13, 1893. This crisis resulted in Siam recognizing France's claims to territories in Laos.

The French knew that the east-bank territories of the Mekong were "depopulated and devastated." Siam's forced movement of people after the Anouvong Rebellion had left only a fifth of the original population on the east bank. Most Lao and Phuan people had been moved to the Khorat Plateau. The territories gained in 1893 were just a starting point for France to control the Mekong, take more land from Siam, and set stable borders with British Burma. France also made a treaty with China in 1895, gaining control of Luang Namtha and Phongsali.

British control of the Shan States and French control of the upper Mekong increased tensions between the two colonial powers. However, a new political party in Paris in 1896 saw Britain more as an ally. In 1904, Britain and France signed the Entente Cordiale, which set their areas of influence in Southeast Asia. This agreement eventually led to their alliance in World War I.

Life Under French Rule (1893–1939)

The French Protectorate of Laos was first managed from Vietnam. In 1899, Laos became centrally managed by a single French official based in Savannakhet, and later in Vientiane. The French chose Vientiane as the capital because it was more central and because they wanted to rebuild the former capital of the Kingdom of Lan Xang that Siam had destroyed.

Laos and Cambodia were seen as sources of raw materials and labor for the more important French territories in Vietnam. The French presence in Laos was small, with only a few thousand Europeans. A French official was in charge of everything, from taxes to justice and public works. The French also had a military presence, mostly Vietnamese soldiers led by French commanders. Vietnamese people held most of the higher and middle-level jobs in the government. Lao people worked as junior clerks, translators, and laborers. Villages still followed the traditional authority of local headmen.

The French focused on building roads and other infrastructure, ending slavery (though forced labor was still used), and collecting taxes. They also encouraged Vietnamese people to move to Laos. By 1943, nearly 40,000 Vietnamese lived in Laos, forming the majority in its largest cities. The French even planned to move more Vietnamese people to key areas, but this was stopped by the Japanese invasion.

The Lao people had mixed feelings about French rule. The nobles preferred the French to the Siamese, but most Lao people were burdened by high taxes and demands for forced labor. The first serious resistance to French rule began in southern Laos with the Holy Man's Rebellion led by Ong Keo, which lasted until 1910. This rebellion started in 1901 when a French official tried to tax Lao Theung tribes. Ong Keo stirred up anti-French feelings, and the French burned a local temple. The official and his troops were killed, and a general uprising began. Ong Keo was killed, but his protests gained popularity.

In the north, Tai Lu groups also rebelled against French taxes and forced labor. In 1914, the Tai Lu king fled to China and started a two-year guerrilla war against the French. In northeast Laos, Chinese and Lao Theung rebels fought against French attempts to tax the opium trade from 1914 to 1917. The French sent a large military force to stop these rebellions. A Hmong shaman named Pa Chay Vue also led a rebellion from 1919 to 1921, trying to create a Hmong homeland.

By 1920, most of French Laos was peaceful. In 1928, the first school for training Lao civil servants was opened, allowing Lao people to take jobs previously held by Vietnamese. In the 1920s and 1930s, France tried to bring Western education, modern healthcare, and public works to Laos, with mixed success. The budget for colonial Laos was small.

During this time, a sense of Lao national identity began to grow. Prince Phetsarath Rattanavongsa and French scholars worked to restore ancient monuments and research Lao history, literature, and art. This French interest in local history helped show that the French were protecting Laos from Siamese rule, and it also supported real scholarship.

World War II and Independence

Lao national identity became more important in 1938 when a very nationalist prime minister, Plaek Phibunsongkhram, came to power in Bangkok. He renamed Siam to Thailand, as part of a plan to unite all Tai peoples under Bangkok's rule. The French were worried, but the Vichy government (the French government during WWII) was busy with events in Europe. Despite a peace treaty, Thailand took advantage of France's weak position and started the Franco-Thai War. This war ended badly for Laos, as it lost territories to Thailand. This made the Lao people distrust the French and led to the first strong national cultural movement in Laos.

World War II didn't greatly affect Laos until February 1945, when a Japanese army unit moved into Xieng Khouang. The Japanese feared that the French government in Indochina would switch loyalty to the Free French (who fought against Germany). So, the Japanese launched "Operation Meigo" to take control. The Japanese arrested French people in Vietnam and Cambodia. But in remote parts of Laos, the French, with help from the Lao and local soldiers, set up jungle bases supplied by the British. However, French control in Laos was greatly weakened.

Lao Issara and Freedom

1945 was a turning point for Laos. Under Japanese pressure, King Sisavangvong declared independence in April. This allowed different independence groups in Laos to unite into the Lao Issara (meaning "Free Lao") movement. This group was led by Prince Phetsarath and opposed France returning to Laos.

When Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, pro-French groups felt stronger, and King Sisavangvong dismissed Prince Phetsarath. But Prince Phetsarath staged a coup in September and put the royal family under house arrest. On October 12, 1945, the Lao Issara government was declared. Over the next six months, the French fought back and regained control of Indochina by April 1946.

The Lao Issara government fled to Thailand. They continued to oppose the French until 1949, when the group split over relations with the Vietnamese communists. The Pathet Lao (Lao Nation) communist group was formed from this split. With the Lao Issara in exile, France set up a constitutional monarchy in Laos in August 1946, with King Sisavangvong as head. Thailand agreed to return the territories it had taken during the Franco-Thai War.

In 1949, an agreement between France and Laos gave most Lao Issara members amnesty and created the Kingdom of Laos. This was a semi-independent monarchy within the French Union. In 1950, the Royal Lao Government gained more powers, including training for a national army. On October 22, 1953, the Franco–Lao Treaty transferred all remaining French powers to the independent Royal Lao Government. By 1954, France lost the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam, ending eight years of fighting in the First Indochinese War, and gave up all its colonies in Indochina.

Kingdom of Laos and the Lao Civil War (1953–1975)

Elections were held in 1955, and the first coalition government, led by Prince Souvanna Phouma, was formed in 1957. This government fell apart in 1958. In 1960, Captain Kong Le staged a coup and demanded a neutral government. A second coalition government, again led by Souvanna Phouma, also failed. Right-wing forces under General Phoumi Nosavan removed the neutral government later that year. The North Vietnamese army invaded Laos between 1958 and 1959 to create the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

A second Geneva conference in 1961–62 declared Laos independent and neutral. But this agreement didn't last, and the war soon started again. North Vietnam's growing military presence in Laos pulled the country deeper into the Second Indochina War (1954–1975). As a result, for almost ten years, eastern Laos was bombed very heavily by the U.S. The U.S. wanted to destroy the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran through Laos, and defeat the communist forces. The North Vietnamese also strongly supported the Pathet Lao and repeatedly invaded Laos. The government and army of Laos were supported by the USA during this conflict. The United States trained both the regular Royal Lao forces and other groups, including many Hmong people.

After the Paris Peace Accords led to the U.S. leaving Vietnam, a ceasefire between the Pathet Lao and the government led to a new coalition government. However, North Vietnam never left Laos, and the Pathet Lao remained largely controlled by Vietnam. After South Vietnam fell to communist forces in April 1975, the Pathet Lao, with North Vietnam's support, took complete power with little resistance. On December 2, 1975, the king was forced to give up his throne, and the Lao People's Democratic Republic was established. About 300,000 people, out of a total population of three million, left Laos by crossing into Thailand after the civil war ended.

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–present)

The new communist government, led by Kaysone Phomvihane, took control of the economy. Many members of the previous government and military, including Hmong people, were sent to "re-education camps." Although Laos was officially independent, the communist government was for many years mostly controlled by Vietnam.

The government's policies caused about 10% of the Lao population to leave the country. Laos relied heavily on aid from the Soviet Union, which came through Vietnam, until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. In the 1990s, the communist party stopped its centralized control of the economy but still holds all political power.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Laos para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Laos para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |