History of bison conservation in Canada facts for kids

The plains bison and wood bison in Canada were hunted a lot during the 1700s and 1800s. Both Indigenous hunters and white hunters took part. By the 1850s, bison were almost completely gone. This led to a big effort to save the few herds left.

The Canadian government's rules for wildlife changed over time. At first, they wanted to simply protect wild areas. Later, they focused on managing bison populations using science. These goals often didn't match up. They wanted to save wildlife, encourage fun outdoor activities, make money from bison, and control Indigenous peoples.

Bison conservation was shaped by how the government saw Canada's North. They wanted to modernize it and control it. Also, the way national parks were managed and new scientific ideas played a role.

Government efforts to save bison started with a law in 1894. It was called the Unorganized Territories Game Preservation Act. This law limited when people could hunt. Bison herds were found and moved to special areas where hunting was not allowed.

In 1909, Buffalo National Park was created in Alberta. It started with about 300 plains bison. By 1916, over 2,000 bison lived there, and the park became too crowded. So, many bison were moved to Wood Buffalo National Park (created in 1922). This park is in north-eastern Alberta.

In Wood Buffalo National Park, plains bison and wood bison mixed. They created a new type of bison called a hybrid. The plains bison also brought new diseases. These diseases spread to the wood bison living there.

When bison numbers crashed in the mid-1800s, Indigenous groups who relied on them had to find new ways to live. In the 1900s, the Canadian government's conservation rules made it even harder for Indigenous peoples. These rules limited hunting and took land for national parks.

The government is still working to save bison today. Parks Canada plans to bring plains bison back to Banff National Park. This will help restore the species and bring more visitors. There's also a business that raises bison for food. This can sometimes conflict with efforts to save wild bison.

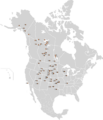

Today, about 400,000 bison live in North America. But only about 20,000 of them are considered truly wild. Many people believe that saving bison means more than just increasing their numbers. It also means helping them return to their wild, undomesticated state.

Contents

Why Bison Numbers Dropped So Much

The Decline of Plains Bison

In the early 1800s, there were around 30 million bison on the Great Plains. But people started hunting them a lot for their valuable hides. This led to too much hunting of the plains bison by both Indigenous peoples and white settlers.

Bison on the western plains were the last to be affected by white American expansion. But by the 1850s, even those herds were shrinking. As more people and farm animals moved west, they destroyed the bison's grazing lands. Dry weather and new diseases also made the problem worse. For a long time, people thought the bison's struggles just showed that humans were stronger than nature.

Some historians say that the idea of making money quickly made both Indigenous and white hunters compete for every last animal. Many things caused the bison to almost disappear. These included disease, dry weather, people moving west, hunting becoming a business, and new animals from Europe.

Others believe the bison's decline was a problem of the "tragedy of the commons". This means that because the bison were owned by everyone, no one felt responsible for keeping their numbers healthy. People hunted for quick gains, which caused big problems later on.

The Decline of Wood Bison

Most of the world's wood bison herds are found in Northern Canada. This is because a small herd was found in the northern part of Wood Buffalo National Park. In 1965, 23 of these bison were moved to the south side of Elk Island National Park. The 300 wood bison living there today are thought to be the purest ones left.

Many things caused the wood bison to decline. The biggest reasons were too much hunting in the 1800s and poor conservation methods. These methods failed to stop them from mixing with plains bison and getting diseases. By the early 1900s, only a few hundred wood bison were left in Northern Alberta.

By 1957, people thought wood bison were completely gone in Canada. This was because they had mixed with plains bison in Wood Buffalo National Park between 1925 and 1928.

To save the wood bison from mixing, special programs were started in 1963. The population slowly grew. However, from the 1970s to the 1990s, their numbers dropped again. This was due to the spread of bovine tuberculosis. This disease came from infected plains bison that were moved to Wood Buffalo National Park. Because of this, the number of wood bison in the park fell from 10,000 in the late 1960s to 2,200 by the late 1990s.

How Hunting Changed Over Time

After horses were brought to North America, some Indigenous groups became nomadic. This meant they moved around and could hunt bison more easily. In the 1800s, bison hunting became a big business. People focused on making quick money instead of thinking about the future.

Historians suggest that the way Indigenous peoples and Euroamericans interacted on the Great Plains led to the bison's near-extinction. New types of bison hunters appeared: Indigenous nomads on horseback and Euroamerican industrial hide hunters. These hunters, along with environmental problems, almost wiped out the bison.

The adoption of horses by Indigenous peoples also led to competition with bison for water and food on the Plains. Industrialization also played a part. Railroads expanded into bison areas, allowing commercial hunting, sometimes even from the trains. The fur trade also grew, increasing demand for bison products.

Early Efforts to Save Bison

The first efforts to save bison in Canada included the Unorganized Territories Game Preservation Act of 1894. This law made a closed season for bison, meaning they couldn't be hunted during certain times. This act was passed after naturalists looked at the bison population and thought it was declining. From this idea, a more active federal wildlife group was created in the Northwest Territories. Wood Buffalo National Park was created in 1922 to help with the wildlife crisis in Northern Canada.

How Wildlife Conservation Started in Canada

For most of the 1800s, the government didn't focus on saving wildlife. They believed there were endless natural resources. They also wanted to develop land for human use. But the bison became a symbol of the wild in North America. As their numbers dropped, they represented the disappearing wilderness.

Protecting bison inspired conservation efforts in Canada. People also wanted to save resources and create places for recreation. Canadian officials were also influenced by the growing wildlife conservation movement in the United States.

Wildlife conservation in Canada also had a practical side. The government wanted to protect animals to attract tourists to parks. Howard Douglas, who managed Rocky Mountains Park starting in 1897, began to protect wildlife. He tried to increase their numbers to bring more visitors to the park.

Between 1900 and 1920, more people became interested in parks. The focus shifted from just tourism to creating the National Parks Branch. Canada was the first country to have a government group just for parks. Other groups, like the Commission of Conservation, were also set up. This commission, started in 1909, was meant to deal with natural resource conservation in Canada.

Over time, environmental protection became more organized. Several government workers, like James Harkin, the first Parks Commissioner, strongly believed in conservation. These officials worked hard to get government support and did their own research. Their efforts led to many environmental protection policies.

Canadian society and the government became more aware and responsible. They started to value wilderness and protect it. The public supported the government in protecting wildlife as a valuable resource, not just for tourism or money. Canada's wildlife conservation movement shows how a small group of dedicated government workers turned their goals of saving endangered species into official government policy.

Government Rules for Bison: How They Changed

From Protecting to Managing

Before World War II, the main goal was to protect bison. This meant "feeding them, shooting animals that hunted them, and stopping poachers." As early as the 1870s, ranchers were catching bison calves and raising them with their cattle. This made the bison more like farm animals.

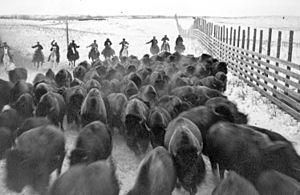

In 1907, the government bought a large herd of plains bison from Montana. They moved them to Buffalo National Park in Alberta. This was because bison numbers in Canada were very low. The park was a good place for their numbers to grow, and they did.

After the war, scientists realized that bison in the north could be used to benefit the country. The idea was that wildlife and wilderness could help the economy in the north. In 1947, the Dominion Wildlife Service (later called Canadian Wildlife Service or CWS) was created. It brought all wildlife research under one government group.

A Canadian biologist named William Fuller studied the hybridized bison in the north. He found that tuberculosis among them helped keep their numbers stable. So, a plan in 1954 included regularly killing some bison to control their population.

Changing Goals for Bison

The 1894 law made a closed hunting season for bison. Plains bison were almost gone in Canada. The government hoped to save them from Indigenous hunters. But saving bison wasn't just for fun activities. After World War II, bison were also used for business.

As bison numbers grew, the government started giving out licenses to control how many could be hunted and to make money. Indigenous people were not allowed in national parks. This was not just to save wilderness, but also for "game conservation, sport hunting, tourism, and to make Indigenous people more like Euro-Canadians." This showed a change in government policy. It moved from protecting wilderness to making money from national parks. Indigenous peoples were kept out of Banff National Park to help conservationists and sports hunters.

Traditional Indigenous hunting practices were seen as conflicting with the government's goal to make Indigenous people adopt Euro-Canadian ways. Starting in the 1880s, Indigenous peoples were encouraged to stop hunting and start farming, like many Euro-Canadians. So, the government wanted to create parks with lots of wildlife for sports hunting and tourism. They also wanted Indigenous people to fit into Euro-Canadian society.

Conflicting Rules

Protecting wood bison in northern Canada meant the government strictly controlled traditional Indigenous hunting. The government even suggested large-scale ranching plans for bison herds. This idea of protecting bison in the north meant the government took power over bison that Indigenous hunters had managed for generations. There was no place for humans to use nature.

In 1952 and 1954, there weren't enough adult male bison. So, managers ordered the killing of more female and young bison to meet their number goals. Wildlife managers were worried by these actions. They feared it would harm the future of the herd. One biologist argued that the bison were declining because of the killings and floods. There was a disagreement between the Wood Buffalo Park management and the federal government. The park staff called the killing of bison "mass murder."

The government's goal of selling bison meat across Canada went against the need to provide cheap bison meat to local people in northern Canada. With new deals with meat companies in the south, over nine hundred bison were killed. The meat companies got top-quality bison meat for low prices. But northern Canada got tough meat that was sold at higher prices. Biologists worried there was no scientific reason for killing so many bison, especially since many didn't have tuberculosis.

In the late 1980s, there was a debate about tuberculosis and brucellosis in Wood Buffalo Park. People discussed whether the diseased bison should be replaced. A committee suggested several options, including killing all the diseased bison and replacing them with healthy ones. This caused a big debate between Environment Canada, who wanted to kill them, and Wood Buffalo National Park staff, who were against it. The park staff argued that the risk of diseased bison infecting cattle was exaggerated. They thought it was just an excuse to use bison for business. Because of the opposition, the diseased bison were not killed.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous peoples were against the creation of Wood Buffalo National Park in 1922. They kept protesting even after it was made. When the park was created, Indigenous peoples who didn't have treaties were removed. Those with treaties could still hunt, but under strict rules from park staff. Indigenous hunting cultures were not considered when these laws were made. The government cared more about saving bison.

After 1945, government wildlife workers became interested in developing the North. They saw the money that bison could bring. A biologist's study of bison with tuberculosis gave the government a reason to kill bison for business and economic reasons.

National Parks and Bison

Buffalo National Park's Role

Buffalo National Park, created in 1909 in Wainwright, Alberta, received its first 325 bison on June 16, 1909. These bison came from Elk Island National Park. The park was made to save plains bison, which were almost extinct by the mid-1880s. This was mainly due to too much hunting, more settlements, and better hunting tools.

After many more bison arrived, the population at Buffalo National Park grew very quickly. It reached over 2,000 by 1916, becoming the largest bison herd in the world. This fast growth seemed like a success. But managers didn't know much about how to best manage wild animal populations.

However, moving plains bison from the crowded Buffalo National Park to the less populated Wood Buffalo National Park caused problems. The species mixed, creating hybrids. The northern herds became sick with tuberculosis and brucellosis carried by the plains bison. This caused the wood bison population to drop.

It wasn't until the 1930s that park managers started to study how animals interact with each other and their environment. They also began to understand "carrying capacity" – how many animals an area can support. The park land was not good for farming. With too many bison, the land got worse, and diseases spread more easily. Experiments like mixing bison with cattle and trying to sell the herd didn't work.

The Canadian Parks Branch didn't have enough money to run the park or fix the bison's problems. After deciding to close the park in 1939, the Department of National Defence (Canada) used the area for military training. The bison disappeared again. But during its 31 years, Buffalo National Park played an important part in saving the plains bison from extinction.

Wood Buffalo National Park's Story

Wood Buffalo National Park, created in 1922, is in northeastern Alberta and the southern part of the Northwest Territories. It is North America's largest national park, covering 44,800 square kilometers. It was made to protect bison herds whose numbers had fallen from an estimated 40 million in 1830 to less than 1,000 by 1900.

Even though the park had diseases like tuberculosis and brucellosis, the bison population grew. It reached between 10,000 and 12,000 by 1934, and 12,500 to 15,000 by the late 1940s and early 1950s.

But by 1998, Parks Canada reported that the population had dropped to about 2,300. This decline was due to many things. These included killings, stopping wolf poisoning, round-ups for disease control, floods, diseases, predators, and changes in their habitat. These big drops, and the loss of pure-strain bison, led to a major debate about the future of bison in the park. People also discussed how to deal with contagious diseases that threatened commercial herds.

In August 1990, a government-supported group suggested bringing disease-free wood bison from Elk Island National Park. But the public quickly reacted negatively, so nothing was done. From 1996 to 2001, a 5-year research program studied how brucellosis and tuberculosis affected the bison in Wood Buffalo National Park. Research continues today to understand this changing ecosystem.

Indigenous Peoples and Government Officials

Past Conflicts Over Bison

The Canadian government's wildlife conservation programs clashed with the traditional hunting cultures of the Cree, Dene, and Inuit peoples. These groups traveled seasonally to hunt bison across large areas. As the government became more involved in managing bison, there were disagreements. These were about access to land and whether bison should be used for Indigenous survival or for making money.

These conflicts happened because Indigenous hunters, government officials, and park managers had different ideas about managing wildlife. The government's scientific approach to bison management did not fit with the traditional hunting cultures of northern Indigenous peoples. The Cree, Dene, and Inuit communities protested government policy. They wrote letters, signed petitions, and refused treaty payments. Less formally, many Indigenous hunters simply ignored the wildlife laws. They were exercising their traditional right to hunt bison.

Government Control Over Indigenous Hunters

The 1894 Unorganized Territories Game Preservation Act put rules in place that greatly limited the Cree, Dene, and Inuit's ability to hunt in their traditional areas. By the 1920s, Indigenous peoples were not allowed to hunt or trap in Wood Buffalo National Park. The park also created a game warden service. This allowed direct watching and control over Indigenous hunters.

Because of this, basic parts of the Indigenous way of life, like seasonal movements, fur trapping, and gathering food, became illegal. This was due to federal game rules. Historians say that ideas about Cree, Dene, and Inuit hunters were often wrong. This was because of biased views, stereotypes, and inaccurate reports from park officials. Also, even if there were times when too many animals were hunted, it doesn't mean Indigenous hunters couldn't manage local bison populations with government experts.

The creation of national parks and game rules was key to the government taking control over the traditional hunting cultures of the Cree, Dene, and Inuit. Historians argue that the early wildlife conservation movement was shaped by the government's goal to "civilize" Indigenous peoples. The government believed that Indigenous hunters in the Northwest Territories were harmful to their scientific approach to wildlife management. This approach was designed to create a surplus of bison that could be sold.

Federal wildlife officials said that Indigenous hunters were destroying bison populations. This made it seem right for the government to control the way of life of the Cree, Dene, and Inuit. The idea that Indigenous hunting was careless, wrong, and wasteful became strong in bison conservation programs. Government officials saw Indigenous hunters as a threat to their plans for wildlife management and development in the north. So, they put them under rules and control.

Impacts on Indigenous Life

The proposed bison ranching plans in Wood Buffalo National Park would have completely changed the lives of Dene and Inuit hunters. Managing bison intensely for business meant bringing in capitalism. It pushed aside the local hunting and trapping economy. It also turned Indigenous hunters into paid workers.

Federal wildlife officials hoped that a northern ranching economy would convince Indigenous peoples to stop hunting and trapping. They wanted them to have more stable lives as workers or ranchers. By the 1950s, government rules controlled almost every part of northern Indigenous peoples' lives. Many Indigenous peoples were encouraged to join the modern economy. Others became dependent on the government. They were moved to reservations or sent to residential schools for "re-education." Not having control over their traditional lands and food sources became a political issue. It affected Indigenous self-determination, culture, and health.

Interactions on the Great Plains

Many Indigenous groups became nomadic bison hunters because of Euroamerican expansion and economic growth. The hide trade became very profitable. The collapse of the bison population on the Great Plains took away the main source of wealth for these groups. It also destroyed their lands and livelihoods.

Both white and Indigenous hunters contributed to the bison's decline. But white hunters often used much more destructive hunting methods. While Indigenous hunting groups hunted bison to support themselves, Euroamericans were actively trying to clear the plains of bison. This was to make way for settlers and farm animals.

Impacts on Bison Populations

Early efforts to save the iconic bison were ultimately hurt by the government's goal to raise northern bison for business. The scientific approach to bison management prevented the government from understanding the complex local ecosystems and human cultures. Focusing only on production led to poor government decisions. For example, thousands of plains bison were moved from the crowded Buffalo National Park to Wood Buffalo National Park.

This move had terrible environmental results. It led to plains and wood bison mixing. It also infected the northern herds with tuberculosis and brucellosis.

Bison Conservation Today

Current Efforts to Save Bison

Today's bison conservation is shaped by the past efforts of the Canadian government. Parks Canada plans to bring back a breeding population of the locally extinct plains bison to Banff National Park. The goals include saving the plains bison, which is a native keystone species (a species that is very important to its ecosystem). Other goals are to restore the environment, inspire discovery, and offer a real "national park experience." Parks Canada says the bison is still a "symbol of the wild Canadian west."

The American Prairie in Montana is also restoring the native prairie ecosystem and growing its bison herds. Plains bison were first moved to this reserve from Elk Island National Park in Alberta.

Even though Indigenous peoples are now more involved in wildlife policy, the old ways of government management still affect things. Current bison conservation plans don't talk about Indigenous use of resources in national parks. It's not clear if Indigenous participation and Traditional Ecological Knowledge will be part of the reintroduction plans.

Some experts say that even though Cree and Dene are now recognized in wildlife management, this shift in power is not complete. The limited power given to Indigenous peoples on wildlife boards allows the government to keep control. It just makes it seem like they are working together with Indigenous hunters.

Today's bison conservation faces many challenges. This is because early preservation methods focused on saving species but sometimes ignored how the ecosystem worked. Now, conservation groups are focusing more on saving bison as a native species. They are also doing research to show if bison should be listed as threatened or endangered.

Non-profit groups are creating conservation herds. Private companies are separating bison herds that don't have cattle genes. Also, Indigenous groups are working to create tribal wildlife reserves with wild bison populations.

The Commercial Bison Industry

The business that raises bison for food can sometimes conflict with conservation efforts. Because the industry sees bison as a product, the bison's role in the grassland ecosystem is often ignored. By the 1960s, wildlife preservation efforts had turned into a bison ranching industry. Many parks in Canada became hard to tell apart from the farms around them. The bison, which symbolized the wild, became "meat" because of the very groups that helped save them.

Many bison herds have mixed with cattle. This happened because of efforts to create "cattalo" when bison numbers were very low in the late 1800s and early 1900s. 2011|lc=y, there are about 400,000 plains bison in North America. But only about 20,000 are considered "wildlife."

These numbers show that saving bison today is more complex than just increasing their population. Modern conservation needs to focus on returning bison to their wild state. This means restoring their native prairie homes. The Canadian Bison Association (CBA), which has over 1,500 producers and 250,000 bison, is working with conservation groups. They are developing plans to help bison return to their natural, wild state.

Images for kids