History of lobbying in the United States facts for kids

The history of lobbying in the United States is about how groups and people have tried to influence government decisions. Lobbying means trying to convince lawmakers, like those in the United States Congress, to make laws that help a specific group or cause. It's different from a regular person asking the government for something.

Lobbying has been around since the very beginning of the United States. It happens at all levels of government, from local towns to the federal government in Washington, D.C. In the 1800s, most lobbying happened in state governments. But in the 1900s, especially in the last 30 years, it grew a lot at the federal level.

Even though lobbying can be controversial, courts have often said it's a form of free speech. This means people have a right to share their opinions with the government.

Contents

Early Days of Lobbying

When the U.S. Constitution was created, important leaders like James Madison wanted a government where no single group could become too powerful. Madison called these powerful groups "factions." He worried that factions could threaten the rights of others or the good of the whole country.

Madison believed that if many different groups competed, no one group could take over. Today, we often call these "factions" by the name "special interests." The Constitution also protects freedoms like free speech.

Lobbying and the First Amendment

Many people believe that the ability of individuals, groups, and businesses to lobby the government is protected by the First Amendment. This amendment includes the right to petition the government. The Supreme Court has often supported these freedoms. Even businesses are sometimes seen as having similar rights to citizens, including the right to lobby.

However, lobbying is a political process, often done privately. This is different from "petitioning," which in the 1700s and 1800s was usually an open, public process in state legislatures and Congress. Back then, petitions were read and discussed in public meetings. Some early state governments even made lobbying illegal because they saw it as a way to corrupt the public process.

Lobbying in the 1800s

During the 1800s, most lobbying happened in state governments. The federal government didn't deal with as many economic issues as states did. When lobbying did happen, it was often done quietly, without much public knowledge.

More intense lobbying at the federal level began around 1869, during President Grant's time. This was the start of the Gilded Age, a time of rapid economic growth. Powerful groups wanted things like money for railroads and taxes on imported goods. In the South, during Reconstruction, lobbying was also strong, especially for railroad money. For example, the Louisiana State Lottery Company actively lobbied state leaders to get permission to sell lottery tickets.

Lobbying in the 1900s

During the Progressive Era (from the 1880s to the 1920s), many reformers believed lobbyists were corrupting politics. People started to think that lobbying should be more open and public. For instance, in 1928, a group called the American Tariff League was criticized for not reporting how much money it spent to help elect Herbert Hoover.

A Famous Lobbyist

One of the most successful lobbyists of this time was Col. John Thomas Taylor. He was the main lobbyist for the American Legion, a group for military veterans. Between 1919 and 1941, he helped pass 630 different laws that benefited veterans, totaling over $13 billion.

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover complained about "a locust swarm of lobbyists" in Congress. Time magazine even named Taylor as one of the highly paid lobbyists. After World War II, Taylor helped improve the G.I. Bill of Rights, a law that provided benefits to returning soldiers.

Defining Lobbying

In 1953, the Supreme Court looked at what "lobbying activities" really meant. The Court decided that "lobbying" mainly referred to "direct" lobbying. This meant talking directly to Congress, its members, or its committees.

The Court said this was different from "indirect lobbying," which means trying to influence Congress by changing public opinion. The Court believed that trying to influence public opinion was a good thing for democracy, not an evil.

It is said that indirect lobbying by the pressure of public opinion on the Congress is an evil and a danger. That is not an evil; it is a good, the healthy essence of the democratic process. ...

—Supreme Court decision in Rumely v. United States

Changes in Politics and Lobbying

Many things changed in the second half of the 1900s that affected lobbying:

- Easy Reelection for Congresspersons: It became much easier for members of Congress to win reelection. Rules about drawing electoral districts (called gerrymandering) and free mailings (called franking privilege) often helped those already in office. Studies showed that over 90% of congresspersons won reelection.

- Expensive Campaigns: Winning reelection meant spending huge amounts of money on things like television ads. This meant congresspersons spent a lot of time raising money instead of focusing on their jobs. For example, in 1976, running for a House seat cost about $86,000. By 2006, it was $1.3 million!

- Lobbyists and Fundraising: Lobbyists used to focus on convincing lawmakers after they were elected. But as campaigns got more expensive, lobbyists started helping congresspersons raise money. They often did this through political action committees, or PACs. These PACs collect money from many businesses and give it to the campaigns of lawmakers they favor.

- Increased Partisanship: Political parties became more divided and unwilling to compromise, especially starting in the 1980s. When districts are drawn to be "safe seats" for one party, it can lead to more extreme views.

- Growing Complexity: More power shifted from state governments to Washington, D.C. Also, new technologies and systems made laws and government actions much more complicated. It became hard for regular people or watchdog groups to understand everything. This led to more specialized lobbying, where lobbyists had to know a lot of detailed information about many issues.

- Earmarks: These are special parts added to a law, often at the last minute, that direct specific money to a particular project. This often benefits a project in a lawmaker's home district. Lobbyists like Gerald Cassidy helped lawmakers use earmarks to send money to specific causes, like universities. Cassidy is even credited with inventing the idea of "lobbying for earmarked appropriations."

- Staffers: Congressional aides, who used to stay in their jobs for many years, started leaving sooner to become lobbyists. This was because lobbying jobs offered much higher salaries.

As a result of these changes, lobbying activity grew incredibly fast in the last few decades. The money spent on lobbying went from "tens of millions to billions a year." In 1975, Washington lobbyists made less than $100 million. By 2006, it was over $2.5 billion! Lobbyists like Gerald Cassidy became very wealthy.

Cassidy made no bones about his work. He liked to talk about his ability to get things done: winning hundreds of millions in federal dollars for his university clients, getting Ocean Spray Cranberry juice into school lunches, helping General Dynamics save the billion-dollar Seawolf submarine, smoothing the way for the president of Taiwan to make a speech at Cornell despite a U.S. ban on such visits.

—Journalist Robert G. Kaiser in the Washington Post, 2007

The Revolving Door

Another big trend that emerged was the "revolving door." Before the mid-1970s, it was rare for a member of Congress to work for a lobbying firm after retiring. If it happened, people were surprised. Back then, lobbying was often seen as a less respected job for former elected officials.

However, by 2007, about 200 former members of the House and Senate were registered lobbyists. Higher salaries for lobbyists, more demand, and changes in Congress helped change attitudes. The "revolving door," where former government officials become lobbyists, became a common practice.

In this new world of Washington politics, the work of public relations and advertising often mixed with lobbying and lawmaking.

Images for kids

-

The Federalist Papers, written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, tried to influence public opinion. This could be seen as an early form of "outside lobbying."

-

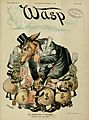

The Louisiana State Lottery Company heavily lobbied the Louisiana state government to get permission to run a lottery business in New Orleans starting in 1866.

-

Creative drawing of electoral districts, called gerrymandering, can make it easier for one party's candidates to win.