History of navigation facts for kids

The history of navigation is all about how people have learned to guide ships and boats across the big, open sea. It's about finding your way and knowing where you are going. For thousands of years, people have used different skills, math, stars, and special tools to travel by water.

Many groups of people have been amazing sailors. These include the Austronesians (like those from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands), the Harappans, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Indians, Vikings, Chinese, and many European nations like the Portuguese, Spanish, English, French, and Dutch.

Contents

Ancient Ways of Finding the Way

Early Sailors in the Indo-Pacific

Navigation in the Indo-Pacific region started with the Austronesian people. They began sailing from Taiwan between 3000 and 1000 BC, moving south into islands like those in Southeast Asia and Melanesia.

Their first long journeys were to Micronesia from the Philippines around 1500 BC. By 900 BC, their descendants, the Polynesians, had sailed over 6,000 kilometers across the Pacific, reaching Tonga and Samoa. Later, Polynesians reached Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island.

Polynesian sailors used many clever methods. They watched birds, used the stars, and even felt the waves and ocean swells to know if land was nearby. They also used songs, stories, and star charts to remember important directions and information.

Around 1000 BC, Austronesians in Southeast Asia started the first real sea trade routes. These connected China, southern India, the Middle East, and coastal East Africa. Some settlers from Borneo even reached Madagascar by 500 AD.

Sailors in the Mediterranean Sea used different ways to find their location. They often stayed close enough to land to see it. They also learned a lot about winds and how they usually blew.

The Minoans from Crete were an early civilization that used the stars to navigate. Their buildings were often lined up with the rising sun on certain days, or with specific stars. The Minoans sailed to places like Thera and Egypt. These trips took more than a day, meaning they traveled at night across open water. They used constellations like Ursa Major (the Big Bear) to keep their ship going in the right direction.

Ancient writings, like Homer's Odyssey, mention using stars for navigation. In the story, Calypso tells Odysseus to keep the Big Bear on his left side while watching other stars like the Pleiades and Orion as he sailed east.

The Greek poet Aratus wrote about the positions of constellations in 300 BC. These positions might have matched the sky over Crete during the Bronze Age. The Earth's slight wobble on its axis changes where stars appear over long periods. Around 1000 BC, the constellation Draco was closer to the North Pole than Polaris is today. Pole stars were useful because they stayed visible all night.

By 300 BC, the Greeks started using Ursa Minor (the Little Bear) for navigation. Later, writers like Lucan described how sailors used stars that never set (circumpolar stars) to find their way. To sail along a certain line of latitude, a sailor needed to find a circumpolar star that appeared above that line in the sky.

A famous early voyage was by Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek navigator. He sailed from Greece through the Strait of Gibraltar to Western Europe and the British Isles. Pytheas was the first known person to describe the Midnight Sun, polar ice, and even mentioned that the Moon causes tides.

Nautical charts and written sailing directions have been used since 600 BC. Some early charts from 200 BC used special map projections. In 1900, the Antikythera mechanism, an ancient Greek device that could predict astronomical positions, was found in a shipwreck. It was built around 100 BC.

Phoenicians and Carthaginians

The Phoenicians and Carthaginians were very skilled sailors. They learned to sail further from the coast to reach places faster. One tool they used was the sounding weight. This was a bell-shaped stone or lead weight with tallow (animal fat) inside, attached to a long rope. Sailors would lower it to find out how deep the water was, which helped them guess how far they were from land. The tallow would also pick up mud or sand from the bottom, which expert sailors could examine to know exactly where they were.

Hanno the Navigator, a Carthaginian, sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar around 500 BC and explored the Atlantic coast of Africa. His expedition likely reached at least as far as Senegal.

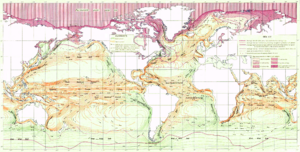

In the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, sailors could use the steady monsoon winds to help them navigate. These winds made long, one-way voyages possible twice a year. A Chinese book from 260 AD described ships with seven sails, called po, used by traders to carry horses. It also mentioned monsoon trade between islands, which took over a month.

Around 1000 BC, Austronesians in Southeast Asia developed the tanja sail and the junk sail. These sails were very important because they allowed ships to sail against the wind. This made it possible to sail around the western coast of Africa. Around 200 AD, the Han dynasty in China developed Chuan (junk ships).

Between 50 and 500 AD, Malay and Javanese trading fleets reached Madagascar. They brought the Ma'anyan people with them as workers. The Malagasy language, spoken in Madagascar, is related to the Southeast Barito language from Borneo. By the 8th or 9th century AD, ancient Indonesian ships might have reached as far as Ghana.

The Arab Empire made big contributions to navigation. They had trade routes that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean and China Sea. Since there weren't many navigable rivers in Islamic lands, sea transport was very important.

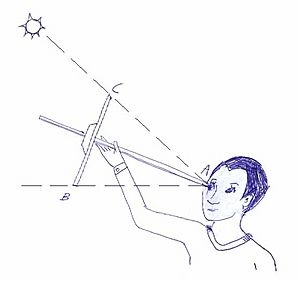

Islamic geographers and scientists used a magnetic compass and a simple tool called a kamal. The kamal was used to measure the height of stars and find latitude. It was a rectangular piece of bone or wood with a string that had nine knots. They also used a quadrant, another tool for celestial navigation, which was first used for astronomy. With these tools and detailed maps, sailors could cross oceans instead of just hugging the coast. However, they mainly sailed in the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, and Bay of Bengal.

Muslim sailors also helped develop the lateen sails and large, three-masted merchant ships in the Mediterranean. The caravel ship, used by the Portuguese for long-distance travel, also has roots in the qarib ships used by explorers from al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) in the 13th century.

Sea routes between India and neighboring lands were used for trade for many centuries. This helped spread Indian culture to Southeast Asia. Powerful navies in India included those of the Maurya, Chola, and Mughal Empires.

The Vikings used a special mineral called a Sunstone to find the Sun even on cloudy days. This helped them navigate their ships. This stone was mentioned in Icelandic writings from the 13th-14th centuries.

In China, between 1040 and 1117, the magnetic compass was developed and used for navigation. This allowed sailors to stay on course even when bad weather hid the sky. The true mariner's compass, with a needle that pivoted in a dry box, was invented in Europe by 1300.

Nautical charts called portolan charts appeared in Italy in the late 13th century. However, they didn't spread quickly; the first report of a nautical chart on an English ship wasn't until 1489.

Age of Exploration

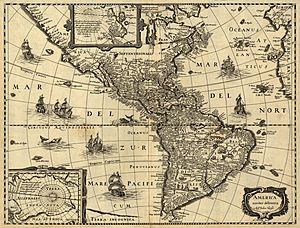

The commercial journeys of Portugal in the early 15th century marked a big step forward in European navigation. Prince Henry the Navigator sent out expeditions that led to the discovery of islands like Porto Santo (1418), the Azores (1427), and the Cape Verde Islands (1447).

Portuguese explorers became leaders in long-distance ocean navigation. They combined their experience at sea with mapping winds and currents. By the early 16th century, they had opened a network of ocean routes across the Atlantic, Indian, and western Pacific oceans, reaching from North Atlantic to Japan and Southeast Asia.

The Portuguese effort to explore the Atlantic was like a big, systematic science project that lasted for decades. They gathered skilled people, set clear goals, and tested their findings through successful voyages.

Portuguese Exploration of the Atlantic

One big challenge for sailing ships returning from south of the Canary Islands was the change in winds and currents. The North Atlantic gyre and Equatorial counter current would push ships south along Africa's coast. Also, the calm winds in the "doldrums" could leave a ship stuck. These conditions made it very hard to sail north.

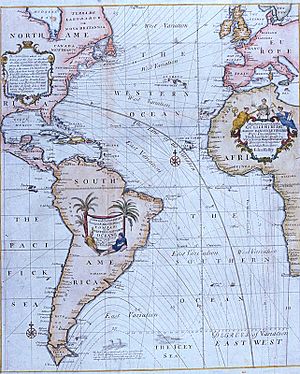

To solve this, the Portuguese discovered two major ocean currents and trade winds, which they called the "volta do mar" (meaning "turn of the sea"). These allowed ships to sail out into the open ocean to catch favorable winds, making it possible to reach the New World and return to Europe, and to sail around Africa. The "rediscovery" of the Azores islands in 1427 showed their new importance as a stop on the return route from Africa.

Duarte Pacheco Pereira, a Portuguese navigator, wrote about his explorations of the African coast and the South Atlantic in his book Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis (1505-1508). He described how to navigate safely, including knowing the depth of waters, the type of seabed, tides, and how to find latitude.

Sailors kept detailed records of their observations in "Roteiros" or maritime route-maps. These included information about coastlines, depths, and tides. The earliest known Roteiro dates back to 1485.

The Portuguese also explored the western North Atlantic. Documents show that they were planning systematic voyages and ordering tables to calculate the sun's position as early as 1493–1496. This deep understanding of ocean conditions helped them negotiate the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This treaty moved the line dividing Spanish and Portuguese claims, giving Portugal a stronger claim to Brazil and control over the Atlantic.

Portuguese Exploration of the Indian Ocean

By the early 16th century, regular voyages between Lisbon and India were common. The knowledge gained in the Atlantic was then applied to the Indian Ocean. A group of brilliant minds, including the mathematician Pedro Nunes and the explorer João de Castro, worked on these challenges.

Pedro Nunes (1502-1578) used mathematics to figure out the "loxodromic curve." This is the shortest path between two points on a sphere when drawn on a flat map. His work helped create the Mercator projection, a type of map widely used for navigation. Nunes stated that Portuguese voyages were not accidental. He said sailors were "well taught and provided with instruments and rules of astrology (astronomy) and geometry."

João de Castro's work focused on the Indian Ocean, especially the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea (1538-1541). He carefully studied the coast, navigation, winds, and currents. He also made important discoveries about Earth's magnetism. He noticed how the magnetic compass needle behaved differently in various places. He even found that certain rocks could affect the compass, a phenomenon later called "local attraction." His observations were very important for understanding Earth's magnetism in the 16th century.

King John II of Portugal continued this effort. He formed a committee on navigation that created tables for the sun's position and improved the mariner's astrolabe. These tools helped sailors find their latitude more accurately. Abraham Zacut, a Jewish scholar, published astronomical tables in 1496. These tables, along with the new metal astrolabe, were likely very helpful to Vasco da Gama and Pedro Álvares Cabral on their voyages to India and South America.

The Spanish Empire also played a big role in global exploration. They opened trade routes across the Atlantic, starting with Christopher Columbus's voyages in 1492. Spain also sponsored the first trip around the world in 1521, led by Ferdinand Magellan and completed by Juan Sebastián Elcano. Later, Andrés de Urdaneta discovered a return route across the northern Pacific.

In Christopher Columbus's time, navigators used a compass, a cross-staff or astrolabe, and basic charts. In 1514, Johannes Werner wrote that the cross-staff was an old tool but was just starting to be used on ships.

Before 1577, sailors estimated a ship's speed by watching its bow wave or floating objects. In 1577, the "chip log" was mentioned as a more advanced technique. In 1578, a device was patented that measured speed by counting the turns of a wheel under the ship.

Accurate timekeeping is needed to find longitude. Early navigators used water clocks and sand clocks, like hourglasses. Hourglasses were used by the British Royal Navy until 1839 to time watches.

More exploration and trade led to more navigation books. French "Routiers" appeared around 1500, and the English called them "rutters." In 1584, Lucas Waghenaer published The Mariner's Mirror, which became a model for navigation books for generations.

In 1537, Pedro Nunes published Tratado da Sphera, which used mathematics to study navigation for the first time. This started a new field called "scientific navigation." In 1545, Pedro de Medina published the important book Arte de navegar, which was translated into many languages.

In 1569, Gerardus Mercator published a world map using the Mercator projection. On this map, a constant compass bearing appears as a straight line. This projection became widely used for nautical charts from the 18th century onward.

In 1594, John Davis published The Seaman's Secrets, which described "great circle sailing" (the shortest path between two points on a sphere). Davis also created a version of the backstaff, called the Davis quadrant, which was a main navigation tool from the 17th century until the sextant was adopted.

In 1599, Edward Wright published Certaine Errors in Navigation. This book explained the math behind the Mercator projection and provided tables to use it. It also pointed out other errors in navigation, like problems with instruments and inaccurate charts.

In 1631, Pierre Vernier invented a quadrant that was very accurate, allowing navigators to find their position within about a nautical mile. In 1635, Henry Gellibrand wrote about the yearly changes in magnetic variation. In 1637, Richard Norwood measured the length of a nautical mile. He also discovered magnetic dip in 1576.

Modern Times

In 1714, the British "Commissioners for the discovery of longitude at sea" were formed. This group offered prizes for solving navigation problems. The British government also offered big rewards, like £20,000 for finding the Northwest Passage. A popular navigation manual in the 18th century was Navigatio Britannica by John Barrow.

Isaac Newton invented a reflecting quadrant around 1699, but his description was published later. John Hadley and Thomas Godfrey are often given credit for it. The octant, a similar tool, replaced older instruments and made latitude calculations much more accurate.

A huge step forward for finding longitude accurately was the invention of the marine chronometer. John Harrison, a carpenter, won the 1714 longitude prize for his invention. In 1761, he completed his H4 chronometer, which looked like a large pocket watch. It used a fast-beating balance wheel and a temperature-compensated spring. These features were used until electronic clocks became available.

In 1757, John Bird invented the first sextant. This tool replaced the Davis quadrant and octant. The sextant was used with the "lunar distance method," which allowed sailors to find their longitude accurately. Once chronometers became more common in the late 1700s, they became the main way to find longitude.

In 1891, radios (wireless telegraphs) started appearing on ships. In 1899, the R.F. Matthews was the first ship to use wireless communication to ask for help at sea. Scientists also started using radio to find direction.

By 1904, time signals were sent to ships by radio so navigators could check their chronometers. The U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office began sending navigation warnings to ships by 1907.

Later, lighthouses and buoys were placed near shore to guide ships, mark dangers, and show safe channels. In 1912, Nils Gustaf Dalén won the Nobel Prize for inventing automatic valves for lighthouses. The first radiobeacon was installed in 1921.

The first prototype ship radar system was put on the USS Leary in April 1937. On November 18, 1940, the idea for an electronic air navigation system, which became LORAN (long range navigation system), was suggested. The first LORAN system started operating in 1942.

In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite. Scientists noticed how its radio signal changed (Doppler shift) and used this to find its position. This led to the idea of using satellites to find a position on Earth. This resulted in the TRANSIT satellite navigation system. The first TRANSIT satellite was launched in 1960, and the system became operational in 1962. A navigator using three satellites could find their position within about 80 feet.

On July 14, 1974, the first prototype Navstar GPS satellite was launched. The Navigational Technology Satellite 2, with improved clocks, went into orbit in 1977. By 1985, the first 11 GPS satellites were in orbit.

Russia's GLONASS system began launching satellites in 1982. The European Space Agency also developed its Galileo system.

Integrated Bridge Systems

Today, navigation systems are becoming more integrated. Modern systems combine information from many ship sensors. They show positioning data electronically and send signals to keep a vessel on its course. The navigator becomes a system manager, setting up the system, understanding its output, and watching how the ship responds.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la navegación astronómica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la navegación astronómica para niños

- Air navigation

- Austronesian navigation

- Celestial navigation

- Galileo positioning system

- History of longitude

- Navigation

- Polynesian navigation

- Portuguese nautical science

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |