Polynesian navigation facts for kids

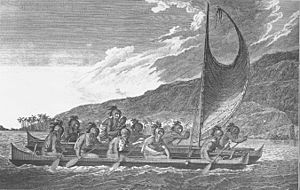

For thousands of years, Polynesian navigation helped people travel huge distances across the Pacific Ocean. Polynesians reached almost every island in the large Polynesian Triangle. They used special canoes, either outrigger canoes or double-hulled canoes. Double-hulled canoes had two large hulls tied together. The space between them was used to store food and tools for long trips.

Polynesian navigators were experts at wayfinding. They used the stars, birds, ocean swells, and wind patterns to guide them. They learned this knowledge from older generations through oral tradition, often in songs.

Each island usually had a group of navigators. These navigators were very important people. If there was a famine, they could trade for help or move people to other islands. Today, these old navigation methods are still taught. You can find them in places like Taumako in the Solomon Islands and by voyaging groups across the Pacific.

The secrets of wayfinding and canoe building were often kept within families or groups. But now, as these skills are being brought back, they are also being written down and shared.

Contents

History of Polynesian Voyaging

Around 3000 to 1000 BC, people speaking Austronesian languages spread through the islands of Southeast Asia. They likely started from Taiwan. From there, they moved into Micronesia and Melanesia, through the Philippines and Indonesia. Scientists can trace this journey through old remains and DNA.

About 1500 BC, a special culture appeared in north-west Melanesia. This was the Lapita culture, known for its large villages on beaches. They made unique pottery with beautiful patterns. Between 1300 and 900 BC, the Lapita culture spread 6000 kilometers east. It reached as far as Tonga and Samoa. Lapita pottery was used for many years in Western Polynesia. But it eventually disappeared because clay was hard to find.

Polynesian stories say that their navigation paths looked like an octopus. Its head was centered on Raiatea in French Polynesia. Its tentacles reached out across the Pacific. This octopus was known by names like "Grand Octopus of Prosperity."

Scientists still discuss the exact dates of island discoveries. But it is generally thought that the Cook Islands were settled before 1000 AD. From there, people sailed in all directions. Eastern Polynesia (like the Society Islands and Marquesas Islands) was settled first. Then came more distant places like Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand. People also sailed north from Samoa to the Tuvalu atolls. Tuvalu became a stepping stone to other Polynesian communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.

The first people on Easter Island probably came from Mangareva. They may have found the island by following the flight of sooty tern birds. When Europeans first arrived at Easter Island, they saw no signs of long-distance navigation. They noticed there were not enough trees to build strong canoes. The rafts the islanders used were not good for ocean travel.

Navigation depended a lot on watching and remembering. Navigators had to remember where they had sailed from. This helped them know where they were going. The sun was a main guide. They followed its exact rising and setting points. After sunset, they used the rising and setting points of the stars. If it was cloudy or during the day, they used winds and ocean swells.

Navigators constantly watched for changes. They noticed changes in their canoe's speed and direction. They also knew the time of day or night. Polynesian navigators used many techniques. These included stars, ocean currents, wave patterns, and even glowing ocean water. They also watched air and sea patterns caused by islands. Bird flights, winds, and weather were also important.

Bird Observation

Certain seabirds, like the white tern, fly out to sea in the morning to find fish. They return to land at night. Navigators looking for land would sail opposite the birds' morning path. They would sail with them at night. Large groups of birds were especially helpful. Navigators also knew that bird behavior changed during nesting season.

Some people believe that Polynesians followed bird migrations for long journeys. Old stories mention bird flights. It is thought that voyagers used land markers that lined up with bird flight paths to distant islands. For example, a trip from Tahiti to New Zealand might have followed the Pacific long-tailed cuckoo. A trip to Hawaii might have followed the Pacific golden plover.

Polynesians may have also carried shore-sighting birds. One idea is that they took a frigatebird with them. This bird cannot land on water because its feathers get wet. Voyagers would release it when they thought land was near. If the bird did not return to the canoe, they would follow it.

The positions of the stars helped guide Polynesian voyages. Stars stay in fixed positions in the sky all year. Only their rising times change with the seasons. Each star has a specific position. It can give a direction for navigation as it rises or sets. Polynesian voyagers would set a direction using a star near the horizon. They would switch to a new star when the first one rose too high. They memorized a specific sequence of stars for each route.

Polynesians also measured how high stars were in the sky. This helped them figure out their latitude (how far north or south they were). They knew the latitudes of different islands. They used a technique called "sailing down the latitude." This meant they sailed until a certain star passed directly over their destination island. They also knew that stars moved similarly over different islands. This helped them understand their latitude. They could then sail with the wind. Finally, they would turn east or west to reach their island.

Some star compass systems list as many as 150 stars with known directions. Most systems use a few dozen. These star compasses may have come from an ancient tool called a pelorus. For navigators near the equator, using stars is simpler. This is because the entire sky is visible. Any star that passes directly overhead moves along the celestial equator.

Polynesians also used ocean waves and swell patterns to navigate. Many islands in the Pacific are in long chains. These island chains have predictable effects on waves and currents. Navigators who lived among islands learned how different islands changed the swell's shape, direction, and movement. This helped them correct their path. Even near an unknown island chain, they might see familiar signs.

When they were close to an island, they could find it by seeing land birds. They also looked for certain cloud formations. They could also see reflections of shallow water on the underside of clouds. It is thought that Polynesian navigators measured travel time between islands in "canoe-days."

Wind creates waves on the sea. Waves that travel away from where they were created are called swells. Stronger winds create larger swells. The longer the wind blows, the longer the swell lasts. Ocean swells can stay consistent for days. Navigators used them to keep their canoe in a straight line. Swells are more reliable than waves, which are affected by local winds. Swells move in a straight direction. This makes it easier for navigators to know if they are going the right way.

Clouds and Sky Color

Polynesian navigators could spot clouds that formed from the white sand of coral islands. The sand reflected heat into the sky. Subtle differences in the sky's color also showed the presence of lagoons or shallow waters. Deep water reflected little light. But the lighter color of lagoons and shallow waters could be seen in the sky's reflection.

In Eastern Polynesia, navigators sailing from Tahiti to the Tuamotus would sail east towards Anaa atoll. Anaa has a shallow lagoon that reflects a faint green color onto the clouds above it. If a navigator drifted off course, they could correct it when they saw this reflection in the clouds.

There is no proof that ancient Polynesian navigators used special devices on their canoes. However, the people of the Marshall Islands in Micronesia used "stick charts" on land. These charts showed islands and the ocean conditions around them. Micronesian navigators made charts from coconut leaf ribs tied to a frame. The curves and meeting points of the ribs showed wave movements. These movements were caused by islands blocking the wind and waves.

How Far Did They Travel?

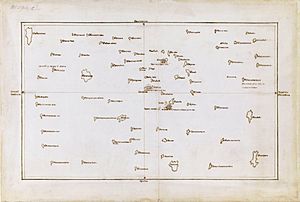

On his first trip to the Pacific, Captain James Cook had a Polynesian navigator named Tupaia. Tupaia drew a map of islands within 2000 miles (3200 km) of his home island, Raiatea. Tupaia knew about 130 islands and named 74 on his map. He had sailed to 13 islands from Raiatea. He had not visited western Polynesia himself. But his grandfather and father had taught him about the major islands there. They also taught him how to sail to Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga.

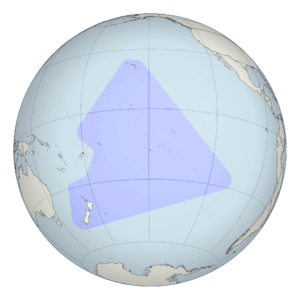

Captain Cook was impressed by how Polynesians had spread across the Pacific. In 1778, he wrote about it. He noted that Polynesians lived from New Zealand in the south to Hawaii in the north. They also lived from Easter Island to Vanuatu. This covered a huge area of the ocean. Cook called them "by far the most extensive nation upon earth."

Voyages to the Antarctic Region

Scientists discuss how far south Polynesians traveled. The islands around New Zealand are called 'South Polynesia.' These include the Kermadec Islands, Chatham Islands, Auckland Islands, and Norfolk Island. Evidence shows Polynesians visited these islands by 1500 AD. Remains of a settlement were found on Enderby Island in the Auckland Islands. This shows Polynesian visits there in the 13th Century.

There are stories of a Polynesian pottery piece found on the Antipodes Islands. But the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa has not found it. They say there is no record of Polynesian influence on it.

An old story tells of Ui-te-Rangiora. Around 650 AD, he led canoes south. They reached "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea." This might describe the Ross Ice Shelf or Antarctica. It could also be icebergs in the Southern Ocean. The story also mentions snow.

Contact with the Americas before Columbus

Some theories suggest Polynesians might have reached the Americas before Christopher Columbus. In the mid-1900s, Thor Heyerdahl suggested Polynesians came from South America. However, this idea is not widely accepted.

Sweet potatoes are plants from the Americas. They were found in the Cook Islands and dated to 1000 CE. This suggests Native Americans might have traveled to Oceania. But most scientists now think Polynesians traveled to South America and brought the sweet potato back. Another idea is that seeds floated across the ocean.

A 2007 study looked at chicken bones in Chile. These bones were dated to before 1424. This was before Europeans arrived. The DNA of these chickens matched chickens from American Samoa and Tonga. These islands are thousands of miles away. This suggested Polynesians brought chickens to South America. However, later studies have debated this. Some say the evidence is not strong enough. Others still support the idea of Polynesian contact.

In 2005, a theory suggested contact between Native Hawaiians and the Chumash people of California. This might have happened between 400 and 800 CE. The Chumash made unique sewn-plank canoes. These canoes were similar to large canoes used by Polynesians. The Chumash word for their canoe, Tomolo'o, might come from a Hawaiian word. However, this theory is not widely accepted by archaeologists. They believe the Chumash developed their canoes on their own.

Some people also suggest contact between Polynesians and the Mapuche culture in Chile. They point to similar cultural things. These include words like toki (stone axes), hand clubs, and sewn-plank canoes. They also note the curanto earth oven (like the Polynesian umu). Fishing methods and a hockey-like game called palín are also similar. Strong winds blow from Polynesia to the Mapuche region. A direct connection from New Zealand is also possible.

A legend from Mangareva tells of Anua Matua. He sailed southwest and reached the southernmost part of South America.

Modern Research and Re-creations

After Europeans arrived, much of the traditional Polynesian navigation knowledge was lost. This led to debates about how Polynesians settled so many distant islands. Some thought it was accidental. For example, Captain James Cook met Tahitians who were lost at sea in a storm. They ended up 1000 miles away. Cook thought this showed how islands could be settled by accident.

Later, people began to admire Polynesian navigation skills. Writers in the late 1800s and early 1900s wrote about heroic Polynesians. They believed Polynesians sailed in large, planned fleets from Asia.

However, historian Andrew Sharp disagreed. He thought Polynesian exploration skills were limited. He believed islands were settled by luck, accidental sightings, and drifting. He said that after islands were found, knowledge was passed down to travel between known places. Sharp's ideas caused a lot of discussion.

Re-creating Voyages

Anthropologist David Lewis sailed his catamaran from Tahiti to New Zealand. He used only star navigation, without instruments. Lewis also met navigators from the Caroline Islands, Santa Cruz Islands, and Tonga. He wanted to confirm that traditional navigation was still used. He sailed with navigators like Tevake and Hipour. He also spoke with many others from Tonga, the Gilbert Islands, and the Caroline Islands.

Anthropologist Ben Finney built Nalehia. This was a 40-foot (12-meter) copy of a Hawaiian double canoe. Finney tested the canoe in Hawaii. At the same time, research in the Caroline Islands showed that traditional star navigation was still used daily. Building and testing canoes inspired by old designs helped. Learning from skilled Micronesians and making voyages using star navigation also helped. This showed how seaworthy traditional canoes were. It also helped understand how Polynesians navigated and how they were adapted to sea travel. Modern re-creations of Polynesian voyages often use Micronesian methods. They follow the teachings of a Micronesian navigator named Mau Piailug.

In 1973, Ben Finney started the Polynesian Voyaging Society. They wanted to prove how Polynesians found their islands. They built copies of ancient Hawaiian double-hulled canoes. These canoes could sail across the ocean using only traditional methods. In 1980, a Hawaiian named Nainoa Thompson created a new wayfinding system. It allowed him to sail from Hawaii to Tahiti and back without instruments. In 1987, a Māori named Matahi Whakataka-Brightwell sailed from Tahiti to New Zealand. He used the canoe Hawaiki-nui without instruments.

In 1978, the canoe Hokulea overturned on its way to Tahiti. Eddie Aikau, a famous surfer and crew member, tried to paddle his surfboard to the nearest island for help. Sadly, Aikau was never seen again. The rest of the crew was later rescued.

In New Zealand, Hector Busby was a leading Māori navigator and ship builder. He was inspired by Nainoa Thompson and Hokulea's visit in 1985.

In 2008, an expedition started in the Philippines. They sailed two modern catamarans. These boats were based on a Polynesian catamaran in the Auckland War Memorial Museum. The boats were built in the Philippines using modern materials. They had modern sails and ropes. The leader, James Wharram, said he used Polynesian navigation to sail along the coast of New Guinea. He then sailed to an island 150 miles away using modern charts. This showed that modern catamarans could follow the Lapita migration path. Unlike some other modern voyages, these catamarans were not towed or escorted by modern boats with GPS. They also had no motors.

In 2010, O Tahiti Nui Freedom, an outrigger sailing canoe, followed the migration path from Tahiti to China. It went through the Cook Islands, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomons, PNG, Palau, and the Philippines. The journey took 123 days.

In 2013, a modern, non-instrument voyage called Mālama Honua was launched. It traveled around the world, starting from Hilo, Hawaii. This was not a re-creation of an old voyage. Its goal was to share a message of conservation. "Mālama honua" means "to care for Earth" in Hawaiian. The journey was made on two vessels: the Hōkūle'a and the Hikianalia. Nainoa Thompson was part of the crew.

Images for kids

-

Antarctica and surrounding islands. The Auckland Islands are just south of New Zealand.

See also

In Spanish: Navegación polinesia para niños

In Spanish: Navegación polinesia para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |