History of longitude facts for kids

The history of longitude is all about how people figured out how to find their exact east-west position on Earth. For a long time, knowing your north-south position (called latitude) was pretty easy using the sun or stars. But knowing your east-west position (longitude) was a huge challenge!

Imagine sailing across a vast ocean. If you don't know your longitude, you could miss your destination by hundreds of miles! This problem puzzled scientists, sailors, and mapmakers for centuries. They needed a way to tell the exact time at a known location (like Greenwich, England) while also knowing the local time where they were. The difference in these times would tell them their longitude.

Early on, people tried using events in the sky, like lunar eclipses, which happen at the same "absolute" moment for everyone on Earth. Later, they invented super-accurate clocks called chronometers. Today, we use amazing technology like satellite navigation (think GPS!) to find longitude with incredible precision.

Contents

Early Ideas About Longitude

The idea of using a grid system with latitude and longitude for maps goes way back to Eratosthenes in ancient Greece (around 200s BCE). He suggested a main line of longitude (called a prime meridian) going through cities like Alexandria.

Later, Hipparchus (around 100s BCE) used a system where the Earth was divided into 360 degrees, just like today. He also had a clever idea: if you could compare the local time of a lunar eclipse in two different places, you could figure out how far apart they were in longitude. This was a great idea, but ancient clocks weren't good enough to make it work accurately.

About 200 years later, Ptolemy created detailed maps using information from travelers. He even used special map designs to reduce distortion. However, his maps often showed places too far apart in longitude, partly because he thought the Earth was smaller than it actually is.

In ancient India, astronomers also knew about using lunar eclipses to find longitude. They had their own prime meridian through a city called Avantī (modern Ujjain).

Islamic scholars, who studied Ptolemy's work, also worked on this problem. In the 900s CE, a scholar named al-Battānī used lunar eclipses to find the longitude difference between two cities with good accuracy. Another scholar, Al-Bīrūnī, in the 1000s CE, developed a method using distances between places to calculate longitude differences. His results were much better than Ptolemy's.

In Europe, after the fall of the Roman Empire, much of this knowledge was lost for a while. But by the 1100s, people started using astronomical tables from Islamic scholars. They even used a lunar eclipse in 1178 to figure out longitude differences between cities like Toledo, Marseille, and Hereford.

By the 1400s and 1500s, with the start of the Age of Discovery, finding longitude became super important for sailors. Christopher Columbus tried to find his longitude during his voyages by watching lunar eclipses. But his results were often very inaccurate.

New Tools: Telescopes and Better Clocks

The 1600s brought two huge inventions that changed everything for longitude:

- The Telescope: In 1608, the refracting telescope was invented. Galileo quickly improved it and made amazing discoveries, like finding the moons of Jupiter. He realized these moons could act like a universal clock!

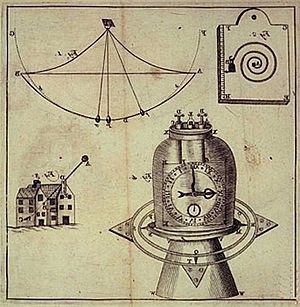

- The Pendulum Clock: In 1657, Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock. This was a massive leap in accuracy, making clocks about 30 times better than before. He hoped they could be used at sea, but the rocking motion of ships made pendulum clocks unreliable there. However, they were perfect for land-based observations.

These new tools opened the door for much more accurate ways to find longitude.

How Longitude Was Found

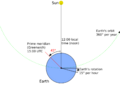

Almost all methods for finding longitude rely on the same basic idea: 1. Find the exact "absolute" time of an event that everyone on Earth sees at the same moment (like a specific star crossing the sky). 2. Compare that absolute time to the local time where you are. 3. Every hour of difference in time means a 15-degree change in longitude.

Here are some of the methods people tried:

Using Jupiter's Moons

After Galileo discovered Jupiter's four brightest moons in 1610, he suggested using their movements as a universal clock. If you knew exactly when a moon would disappear or reappear behind Jupiter (an "eclipse"), you could compare that to your local time.

Galileo even designed a special helmet called a celatone with a telescope to help sailors observe Jupiter's moons from a moving ship. But it was too hard to use at sea. On land, however, this method was very useful and accurate. Astronomers like Giovanni Domenico Cassini published detailed tables of Jupiter's moons, helping to map out countries like France more accurately.

Lunar Distances

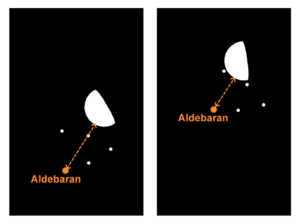

This method involves measuring the angle between the Moon and certain "fixed" stars. Because the Moon moves quite quickly across the sky (about half a degree per hour), a very accurate measurement of this angle could tell you the absolute time.

The challenge was that you needed extremely precise measuring tools and complex tables to account for the Moon's irregular orbit. Early attempts were not very accurate, but over time, this method became very important for navigation.

Chronometers: The Portable Clock

The idea of carrying a very accurate clock, set to the time of a known starting point, was first suggested in 1530 by Gemma Frisius. If you knew the time back home and your local time, you could easily find your longitude.

The problem was, clocks weren't good enough. They lost or gained too much time each day, especially on a rocking ship. This changed with John Harrison, a carpenter from Yorkshire, England. He spent over 30 years building incredibly accurate clocks, called marine chronometers, that could keep time perfectly at sea.

Harrison built five chronometers. His fourth one, H-4, was tested on a voyage to the West Indies in 1762 and met all the requirements for a huge prize offered by the British government. Even though he had to fight for it, Harrison eventually received his reward.

Governments Step In

Because finding longitude was so important for trade and naval power, European countries offered big prizes for a solution.

- Spain: Philip II of Spain offered a reward in 1567.

- Holland: Offered 30,000 florins in the early 1600s.

Neither of these early prizes led to a working solution.

In the late 1600s, France and Britain set up official observatories:

- Paris Observatory (1667): This observatory helped survey France. By using Jupiter's moons, they discovered that previous maps showed the French coastline too far west. King Louis XIV even joked that his astronomers had taken more territory from France than he had gained in all his wars!

- Royal Observatory, Greenwich (1675): This observatory was created specifically to solve the longitude problem. The first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, was tasked with mapping stars to help sailors find their way.

In 1714, the British Parliament passed the "Longitude Act", offering a massive prize (up to £20,000, a fortune at the time!) for a method that could determine longitude at sea within half a degree.

This prize led to two main solutions: 1. Lunar Distances: Tobias Mayer created accurate tables for the Moon's position. Nevil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal, then started publishing an annual nautical almanac in 1767. This book contained pre-calculated lunar distances, making it easier for sailors to use this method. This almanac became a worldwide standard and helped make the Greenwich Meridian (the line of longitude through Greenwich) an international reference point. 2. Chronometers: As mentioned, John Harrison's work finally made accurate sea clocks a reality.

Chronometers vs. Lunar Distances

For a while, both methods were used. Chronometers were very expensive at first, and lunar distance calculations were complicated.

- Lunar Distances: Were often used by land surveyors and explorers, as they didn't rely on expensive clocks. However, each calculation could take hours.

- Chronometers: Became more affordable and reliable over time. They were much simpler to use at sea. You just needed to know your local time and compare it to the chronometer's time.

Ships often carried several chronometers. Three chronometers were ideal because if one showed a different time, you could trust the two that agreed. This led to the saying: "Never go to sea with two chronometers; take one or three."

By the mid-1800s, chronometers had largely replaced lunar distances as the main way to find longitude at sea.

Longitude on Land: Telegraphs and Radio

On land, surveying continued to improve with chronometers. But a new invention, the telegraph, revolutionized longitude determination.

- Telegraphy: In the 1840s, people realized they could use the telegraph to send time signals instantly across long distances. This meant observatories far apart could synchronize their clocks with incredible accuracy. The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey used this "American Method" to map out the entire country. By 1902, the telegraphic network circled the globe, allowing for super-accurate longitude measurements everywhere.

- Wireless Methods: After Guglielmo Marconi invented wireless telegraphy (radio) in 1897, it became even easier to send time signals. By 1907, wireless time signals were being broadcast for ships at sea, allowing them to check and adjust their chronometers frequently.

After World War II, radio navigation systems like LORAN and Omega became common. These systems used radio signals from fixed beacons to help ships find their position, even in bad weather.

Today, we have satellite navigation systems like GPS. These systems use signals from satellites orbiting Earth to tell you your exact position (latitude, longitude, and even altitude) with amazing accuracy, anywhere on the planet. The centuries-long search for longitude has truly been solved!

Images for kids

-

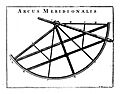

John Flamsteed's mural arc, used for precise observations.

-

Detail of a nautical chart of Paita, Peru, showing a telegraphic longitude determination from 1884.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la longitud para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la longitud para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |