John Harrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Harrison

|

|

|---|---|

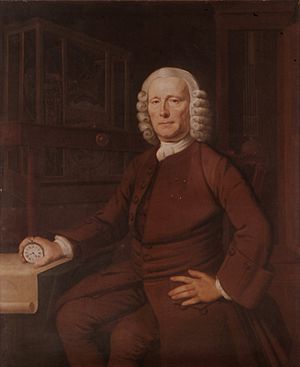

Thomas King's 1767 portrait of John Harrison, located at the Science and Society Picture Library, London

|

|

| Born | 3 April [O.S. 24 March] 1693 Foulby, near Wakefield, West Riding of Yorkshire, England

|

| Died | 24 March 1776 (aged 82) London, England

|

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Bimetallic strip Gridiron pendulum Grasshopper escapement Longitude by chronometer Marine chronometer |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1749) Longitude rewards (1737 & 1773) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Horology & Carpentry |

John Harrison (born April 3, 1693 – died March 24, 1776) was a super clever English carpenter and clockmaker. He taught himself everything he knew! He invented the marine chronometer, which is a special clock that could keep perfect time at sea. This invention solved a huge problem: how to figure out a ship's exact east-west position, called longitude, while sailing.

Harrison's amazing invention changed navigation forever. It made long sea journeys much safer. Before him, many ships got lost or crashed because they couldn't tell their exact location. This problem was so important that the British government offered a huge prize of up to £20,000 (a massive amount of money back then!) to anyone who could solve it. This prize was part of the 1714 Longitude Act. Even though Harrison solved the problem, he had a tough time getting the full prize because of some political issues.

Harrison showed his first design in 1730. He spent many years making better versions, creating new technologies for keeping time. He eventually focused on what he called "sea watches." The Board of Longitude helped him by supporting his work and testing his designs. Towards the end of his life, he finally got the recognition and money he deserved from Parliament. In 2002, a BBC poll even named him one of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Contents

Early Life and Clever Inventions

John Harrison was born in Foulby, a small village in Yorkshire, England. He was the first of five children. His stepfather was a carpenter at a nearby estate called Nostell Priory.

Around 1700, John's family moved to Barrow upon Humber. John followed in his father's footsteps as a carpenter. In his free time, he loved to build and fix clocks. There's a story that when he was six, he had smallpox and was given a watch to play with. He spent hours listening to it and studying its tiny moving parts. This showed his early fascination with how things worked!

He also loved music and became the choirmaster for the church in Barrow.

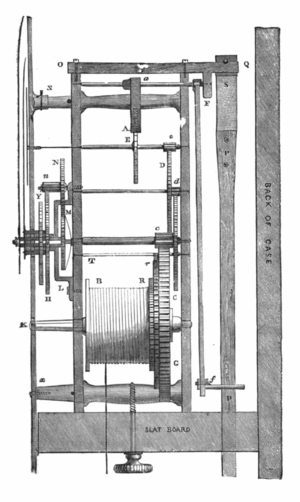

John built his first tall clock in 1713 when he was 20. The whole inside of the clock was made of wood! Three of his early wooden clocks still exist today. One is in the Science Museum in London, another is also there, and a third is at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire. The Nostell clock even has clear sides so you can see the wooden gears working!

John Harrison got married twice. First to Elizabeth Barret in 1718, and after she passed away, he married Elizabeth Scott in 1726.

In the early 1720s, Harrison was asked to build a new turret clock for a place called Brocklesby Park. This clock still works today! Like his other clocks, it had wooden parts made from oak and lignum vitae. But this clock also had new features to keep time even better, like the grasshopper escapement. This was a special part that helped control the clock's movement.

Between 1725 and 1728, John and his brother James, who was also a skilled carpenter, made at least three very accurate tall clocks. These clocks also used wooden parts. During this time, John invented the gridiron pendulum. This pendulum was made of different metals (brass and iron) that expanded and shrunk in opposite ways when the temperature changed. This meant the pendulum stayed the same length, making the clock much more accurate! Many people think these clocks were the most accurate in the world at that time.

Harrison was a genius at improving clocks. He also invented the "grasshopper escapement." This part helped release the clock's power step-by-step. It had almost no friction and didn't need oil, which was a big deal because oils back then weren't very good and could mess up the clock.

A famous clockmaker named George Graham helped Harrison a lot with money and advice. The Astronomer Royal, Edmond Halley, introduced them. This support was very important for Harrison, as he sometimes found it hard to explain his ideas clearly.

The Big Problem: Finding Longitude

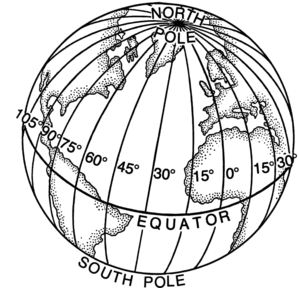

Imagine a map of the Earth with lines going from the North Pole to the South Pole. These lines are called longitude lines. They tell you how far east or west a place is from a special starting line called the prime meridian. Knowing your longitude was super important for sailors, especially when they were close to land. If they didn't know their exact east-west position, they could easily crash their ship after a long journey. In Harrison's time, trade and sailing were growing fast, so avoiding shipwrecks was a huge deal!

Many ideas were suggested to find longitude at sea. One common idea was to compare the local time on the ship with the known time at a reference place, like Greenwich in England. This meant you needed a clock that could keep perfect time, no matter what.

Harrison decided to solve the problem directly by building a super reliable clock. But this was incredibly difficult! The clock had to work perfectly even with changes in temperature, pressure, or humidity. It also had to stay accurate for a long time, resist salty air, and keep ticking on a constantly moving ship. Many smart scientists, like Isaac Newton, thought it was impossible to build such a clock. They preferred other methods, like using the moon's position.

Harrison's First Sea Clocks

Before Harrison, another clockmaker named Henry Sully tried to make a clock for finding longitude in the 1720s. His clock worked well only when the sea was calm. Harrison's clocks, though much bigger, were similar in some ways.

In 1730, Harrison designed his own sea clock to try for the Longitude prize. He went to London to get help with money. He showed his ideas to Edmond Halley, who then sent him to George Graham, a top clockmaker. Graham was so impressed that he lent Harrison money to build a model of his "Sea clock." Harrison used wooden wheels and his special "grasshopper" escapement. Instead of a pendulum, he used two linked weights that swung back and forth.

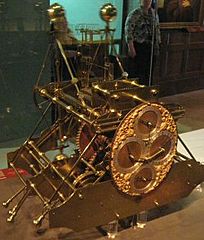

It took Harrison five years to build his first sea clock, known as H1. He showed it to members of the Royal Society, who told the Board of Longitude about it. The Board thought it was good enough for a real test at sea. In 1736, Harrison sailed to Lisbon on a ship called HMS Centurion.

The clock lost some time on the way there, but it worked very well on the way back! The captain and sailing master of the ship praised Harrison's design. The master said his own calculations had put the ship 60 miles off course, but Harrison's clock had correctly predicted their true location.

This wasn't the long trip across the Atlantic that the Board wanted, but they were impressed. They gave Harrison £500 to keep working. By 1737, Harrison had moved to London and started building H2, a smaller and stronger version. By 1741, H2 was ready. But Britain was at war, and the clock was too important to risk it falling into enemy hands. Harrison then stopped working on H2 because he found a big problem with its design. He realized that the ship's movements could affect the clock's accuracy. This made him decide to use round balance wheels in his next clock, H3.

The Board gave him another £500, and Harrison spent 17 years working on H3. Even with all his effort, H3 didn't work exactly as he wanted. The problem was that Harrison didn't fully understand how the springs in the clock worked, which affected its accuracy. However, building H3 taught him a lot. He invented two important things during this time: the bimetallic strip (used in thermometers) and the roller bearing (used to make things move smoothly).

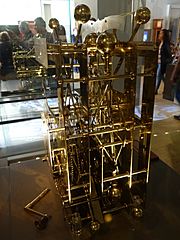

- Harrison's first three marine timekeepers

The Amazing Sea Watches

After 30 years of trying different methods, Harrison was surprised to find that some smaller watches made by another clockmaker, Thomas Mudge, were just as accurate as his huge sea clocks. This was partly because of a new, stronger steel that had become available.

Harrison then realized that a small watch could actually be accurate enough for the job. And a watch would be much easier to use on a ship than a giant clock! So, he decided to redesign the idea of a watch based on good scientific rules.

The "Jefferys" Watch

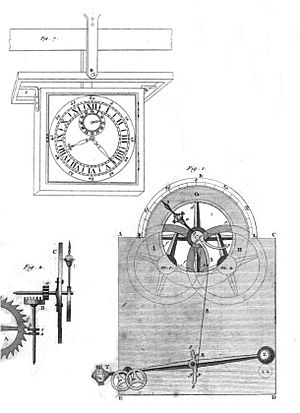

In the early 1750s, Harrison designed a very precise watch for himself. It was made by a watchmaker named John Jefferys. This watch had a new type of escapement and was the first to adjust for temperature changes. It also had a tiny "fusee" that allowed the watch to keep running even while it was being wound. These features made the "Jefferys" watch work very well. Harrison used these ideas for his next two timekeepers.

H4: The Masterpiece

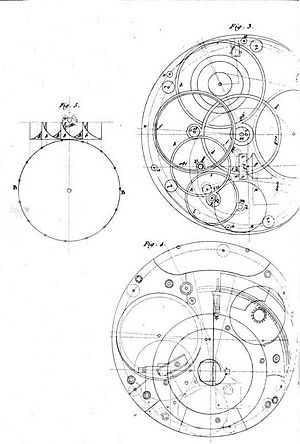

Harrison's first "sea watch," now known as H4, was his greatest work. It looked like a very large pocket watch. It was about 5.2 inches (13 cm) across and was signed by Harrison himself, dated 1759.

The inside of H4 was very complex for its time. It had a coiled steel spring that powered it for 30 hours. It also had a special part called a "maintaining power" that kept the watch running even when it was being wound. The tiny parts of its escapement were made of diamond, which was amazing for that time! The watch ticked five times per second. It also had a special "compensation curb" that used a bimetallic strip to adjust for temperature changes.

This first watch took six years to build. The Board of Longitude decided to test it on a voyage from Portsmouth, England, to Kingston, Jamaica. Harrison, who was 68 years old, sent his son, William, with the watch on HMS Deptford in 1761.

When the ship reached Jamaica, after correcting for a small initial error, the watch was only 5 seconds slow compared to the known longitude of Kingston. This meant an error of only about one nautical mile! William Harrison returned to England in 1762 with the good news.

Harrison senior expected to get the £20,000 prize. But the Board thought the accuracy might have been just luck. They also felt that a clock that took six years to build wasn't practical enough. The Harrisons were very upset and demanded their prize. The issue eventually went to Parliament, which offered £5,000 for the design. The Harrisons refused, but they eventually had to agree to another test trip to Bridgetown, Barbados.

During this second test of H4, another method for finding longitude was also being tested: the Method of Lunar Distances, which used the moon's position. Again, H4 proved to be incredibly accurate, keeping time to within 39 seconds. This meant an error of less than 10 miles (16 km) in longitude! The moon method was also good, but it needed a lot of hard work and calculations.

At a meeting in 1765, the Board heard the results, but they still thought H4's accuracy was just luck. The matter went back to Parliament, which offered Harrison £10,000 upfront. He would get the rest once he shared his design with other clockmakers so they could copy it. Meanwhile, H4 had to be given to the Astronomer Royal for long-term testing on land.

Unfortunately, Nevil Maskelyne had become the Astronomer Royal and was also on the Board of Longitude. He gave a negative report about H4, saying its accuracy was just a coincidence. Because of this, Harrison's watch failed the Board's requirements, even though it had succeeded in two sea trials!

Harrison started working on his second "sea watch" (H5) while H4 was being tested. He felt the Board was holding his watch "hostage." After three years, he had had enough. Harrison felt very unfairly treated and decided to ask King George III for help. The King was very annoyed with the Board. King George himself tested H5 at the palace between May and July 1772. After ten weeks of daily checks, he found it was accurate to within one-third of a second per day!

King George then told Harrison to ask Parliament for the full prize, threatening to speak to them himself if they didn't listen. Finally, in 1773, when he was 80 years old, Harrison received £8,750 from Parliament for his amazing work. He never got the official £20,000 prize, which was never actually given to anyone. He passed away just three years later.

In total, Harrison received £23,065 for his work on chronometers. This gave him a good income for most of his life. He became very wealthy by the end of his life.

Captain James Cook used a copy of H4, called K1, on his second and third voyages. Cook's ship logs are full of praise for the watch. The maps he made of the southern Pacific Ocean using it were incredibly accurate. Another copy, K2, was used by Lieutenant William Bligh on HMS Bounty, but it was taken by Fletcher Christian during the famous mutiny.

At first, these chronometers were very expensive. But over time, their cost dropped. While the moon method was also used, chronometers became the main way to find longitude in the 19th century.

Harrison's accurate timekeeping device led to the much-needed precise calculation of longitude. This made his invention a key part of the modern age. Later, other clockmakers like John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw made chronometers simpler and cheaper to produce in large numbers.

By the early 1800s, sailing without a chronometer was considered very risky. Using a chronometer saved lives and ships. Insurance companies and common sense made sure that this device became a universal tool for sea travel.

Death and Tributes

John Harrison died on March 24, 1776, when he was 82 years old. He was buried in the graveyard of St John's Church, Hampstead, in London, along with his second wife and son. His tomb was fixed up in 1879.

Harrison's last home was at 12, Red Lion Square in London. There's a blue plaque on a building there that remembers him. A special memorial was also put up for Harrison in Westminster Abbey on March 24, 2006. This finally recognized him alongside other famous clockmakers buried there. The memorial shows a meridian line to highlight his invention of the bimetallic strip thermometer.

In 2008, the Corpus Clock in Cambridge was unveiled. It's a modern clock that pays tribute to Harrison's work. It even has a part that looks like a grasshopper, just like Harrison's "grasshopper escapement."

In 2014, a train was named John 'Longitude' Harrison in his honor. On April 3, 2018, Google celebrated his 325th birthday with a special Google Doodle on its homepage. In February 2020, a bronze statue of John Harrison was put up in Barrow upon Humber.

Harrison's Legacy

After World War I, Harrison's amazing timepieces were found again at the Royal Greenwich Observatory by a retired naval officer named Rupert T. Gould.

The clocks were in very bad shape, and Gould spent many years fixing and restoring them. He was the first to call them H1, H2, H3, H4, and H5. Gould wrote a famous book called The Marine Chronometer in 1923, which told the whole story of chronometers and Harrison's work. This book is still the most important book about marine chronometers.

Today, the restored H1, H2, H3, and H4 clocks can be seen at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. H1, H2, and H3 still work! H4 is kept stopped because it needs oil to run, and running it would cause wear and tear. H5 is owned by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers and is displayed at the Science Museum, London.

In his later years, John Harrison also wrote about musical tuning and how to make bells. He had some very interesting ideas about music and sound.

One of his boldest claims was that he could build a land clock that would be incredibly accurate – losing only one second in 100 days! People at the time made fun of him for this idea. Harrison drew a design for such a clock, but he never built it himself. However, in 1970, a clockmaker named Martin Burgess studied Harrison's plans and decided to build the clock. He made two versions, called Clock A and Clock B.

Clock B was eventually acquired by Donald Saff and sent to the National Maritime Museum for study. In 2015, Clock B was tested for 100 days at the Royal Observatory. It lost only 5/8 of a second! This proved that Harrison's design was brilliant. Even though this modern clock used materials Harrison didn't have, it showed his idea was sound. Guinness World Records has even called Martin Burgess's Clock B the "most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free air."

In Books, TV, and Music

In 1995, a book called Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time was written by Dava Sobel. It became a popular bestseller and told the story of Harrison's work. An illustrated version came out in 1998.

The book was made into a TV series called Longitude in 1999. It starred Michael Gambon as Harrison and Jeremy Irons as Gould. The book was also featured in a PBS show called Lost at Sea: The Search for Longitude.

Harrison's sea timekeepers were a big part of a 1996 Christmas TV special of the British comedy show Only Fools And Horses. In the story, a fictional watch by Harrison was found and sold for a huge amount of money.

There are also songs and music pieces inspired by John Harrison. The song "John Harrison's Hands" was written by Brian McNeill and Dick Gaughan. Composer Peter Graham wrote a piece called Harrison's Dream about Harrison's long journey to create an accurate clock.

Works

- (in en) Principes de la montre. Avignon: veuve François Girard & François Seguin. 1767. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=617949.

See also

In Spanish: John Harrison para niños

In Spanish: John Harrison para niños

- History of longitude

- Lunar distance (navigation)

- Marine chronometer

- The Island of the Day Before – Umberto Eco

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |