History of the Aromanians facts for kids

The Aromanians are a group of people who live in the Balkans. They speak the Aromanian language, which is similar to Romanian. For a long time, they have been known as Vlachs. They have a rich history, living in different countries like Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, and North Macedonia.

Contents

Who Are the Aromanians?

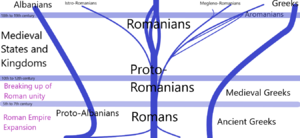

In the Middle Ages, Aromanians were called Vlachs. This was a common name for people in the Balkans who spoke languages similar to Latin. These Vlach people, especially in the southern Balkans, are thought to be descendants of ancient groups like the Thracians and Illyrians, mixed with people from the Roman Empire.

Many Vlachs moved to the mountains in Greece and other Balkan areas. They did this to escape invasions from groups like the Germanic tribes and Bulgars between the 5th and 7th centuries. Today, you can find Aromanians in Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, and North Macedonia. Romanians, another Vlach group, live in Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Serbia, and Hungary.

Aromanians traditionally worked as traders, shepherds, and craftsmen. Language studies show that the Aromanian language was spoken in the southern Balkans. This includes areas like Epirus, Macedonia, and Thrace. By the 10th century, it had separated from the larger language group that became Common Romanian.

Aromanian History Through the Ages

The Byzantine Era

The Byzantine Empire was a powerful state in the Middle Ages. In 980, Emperor Basil II gave control over the Vlachs in Thessaly to a leader named Nikulitsa.

Later, in 1066, the Vlachs had their first uprising against the empire. This was led by Nikoulitzas Delphinas. After the Byzantine Empire fell apart during the Fourth Crusade, the Vlachs created their own independent area. It was called "Great Wallachia".

A traveler named Benjamin of Tudela visited Thessaly in 1173. He wrote that the Vlachs lived in the mountains. They would come down to attack the Greeks. He also noted that "no Emperor can conquer them."

Another Vlach leader, Ivanko, created a small independent land. This was between the Maritsa and Struma rivers. He encouraged Vlachs to settle in these areas. Niketas Choniates wrote about a Vlach named Dobromir Chrysus. He also set up an independent area near the Vardar river.

Many historical writings mention "Great Wallachia" in Thessaly. There were also "Little Wallachia" and "Upper Wallachia" in other parts of Greece. These were some of the first Vlach states in the Balkans. After 1210, when Epirus took over Thessaly, the Vlachs became important soldiers. They fought against the Latin Crusaders and other rival states.

Life Under the Ottoman Empire

During the time of the Ottoman Empire, Aromanian culture and economy grew stronger. Many Vlachs moved to big cities. For example, the city of Moscopole became one of the largest in the Balkans. It had about 60,000 people. At that time, Athens was a small village with only 8,000 people.

Moscopole had its own printing press and schools. It even had running water and a sewer system. Aromanians had some freedom for their religion and culture. They were part of the Greek Orthodox Millet. A "millet" was a special group for non-Muslims in the Ottoman Empire. They were allowed to carry weapons and paid a small tax to the Ottomans.

However, in 1778, Moscopole was almost completely destroyed by the troops of Ali Pasha. This event, along with their Orthodox Christian faith, led many Vlachs to fight against Ottoman rule. They played a big part in the wars and revolutions that created the modern countries they live in today. These countries include Albania, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Greece.

Many Aromanians became important in early Greek politics. This was because they were part of the Greek Orthodox Millet. They often learned Greek in schools and churches. So, the Ottomans saw them as Greeks. For example, Patriarch Athenagoras, a famous religious leader, was born in Ottoman Epirus and seen as Greek.

But some Vlachs wanted to keep their own language and customs. There was a strong effort to make them speak Greek. This started in the 18th century. A Greek missionary named Cosmas of Aetolia taught that Aromanians should speak Greek. He said it was "the language of our Church." He also opened many Greek schools. Some Greek clergy even called the Aromanian language "worthless" and "repulsive."

The Awakening of Aromanian Identity

The 1800s were a time of change for Aromanians. Ideas from the French Revolution spread across Europe. These ideas were about nationhood, equality, and human rights. In Transylvania, Aromanians connected with Romanian thinkers. This led to a period called the National Awakening of Romania.

During this time, important Aromanian figures emerged. One was Gheorghe Roja, who wrote about Romanians and Vlachs. He also tried to create a written language for "Macedo-Romanians." Another was Mihail G. Boiagi, who published a grammar book for the Aromanian language in 1813. He believed Aromanians had a right to use their mother tongue.

In 1865, Dimitrie Cozacovici helped print a Romanian grammar book. This book was meant to help open the first Romanian school in Macedonia.

Romanian Support for Aromanian Schools

Around 1860, nearly 100 Romanian schools opened in Ottoman areas like Macedonia and Albania. This idea came from Aromanians living in Bucharest, Romania. A group of Aromanians, including D.D. Cozacovici, started the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society. This group had support from Romanian leaders. Even the Prime Minister and the head of the Romanian Orthodox Church were members.

One key figure in the Aromanian awakening was Apostol Margarit. He was from Avdela in southern Macedonia. In 1862, he started teaching in the Aromanian language in a school in Klissoura. The Greek bishop of Kastoria tried to close the school, but failed. Margarit was even attacked twice.

More Vlach schools were founded in Macedonia. A Vlach high school opened in Bitola in the 1880s. Before the Balkan Wars, there were 6 high schools and 113 primary schools teaching in Aromanian. The Greek Church saw these schools with suspicion. In 1880, Greek fighters attacked villages where priests used Aromanian in church.

In 1903, the Aromanian group Society Farsharotu was founded in the United States. A very important day for Vlachs was May 23, 1905. On this day, the Sultan officially recognized the Vlachs. He said they had the right to have their own schools and churches. This was called the Ullah millet ("Vlach millet").

After this, Greek bishops and armed groups attacked Aromanians. They wanted to stop them from using their new rights. In 1905, a Vlach abbot was murdered. Villages were attacked, and the school in Avdela was burned down. This led to protests in Bucharest and a break in relations between Romania and Greece.

The day the Sultan's decree was announced, May 23, 1905, is now celebrated as Aromanian National Day. Romania continued to support these schools until 1948, when the communist government stopped all links.

George Padioti, an Aromanian writer, described one of the last church services in Aromanian. It was in February 1952. The priest, Costa Bacou, held the service in Aromanian. But he was not allowed to do it again because he refused to use Greek.

Some Greek historians say that Aromanians who went to Romanian-sponsored schools were victims of Romanian propaganda. They suggest these schools taught children that they were Romanians.

The Vlachs were recognized as a separate group in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. But they became part of Greece only in 1881. This happened when Thessaly and part of Epirus were given to Greece. Many Vlachs wanted to stay in the Ottoman Empire, but they could not. Most Aromanians became part of Greece in 1913 after the First Balkan War.

Around this time, Western observers started writing about Aromanians. Writers like Rebecca West and Sir Charles Eliot mentioned them. Osbert Lancaster visited Greece in 1947. He described the Vlachs as nomads, often shepherds. He noted they were often fairer and harder working than Greeks. He also said they were "not Greek at all but a race of nomads."

Between the World Wars and World War II

The years between World War I and World War II were important for Aromanian history. Many Aromanians moved away in the early 1900s. One reason was Greece's policy of settling many Greeks from Asia Minor after 1923. Also, Romania offered land and benefits to Aromanians to settle in its new province of Dobruja. Today, about 25% of Dobruja's population has Aromanian roots.

During World War II, Italy occupied Greece. Some Aromanians saw this as a chance to create a "Vlach homeland." This short-lived state was called the Principality of Pindus. But it did not last long after Italy left the war in September 1943.

Aromanians in Greece Today

Today, it has been over 50 years since the last Aromanian schools and churches closed. The old term "Vlachos" is sometimes still used in a negative way by Greeks.

After the military government in Greece fell in 1974, local groups formed. They wanted to save the Aromanian language and culture. These groups never got government support. The Aromanian language was never taught in Greek schools. It was often seen as a common, less important language. This led many Aromanian parents to discourage their children from learning it. They wanted to avoid discrimination. Today, there is no public education or media in Aromanian.

In 1997, the Council of Europe looked into the situation of Aromanians. They said the Greek government should help protect their culture. They also suggested supporting education in Aromanian. But many Greek Vlachs do not want the language in schools. They see it as creating a divide between them and other Greeks. For example, a former education minister suggested a trial program for Aromanian language education. Aromanian mayors and groups rejected it.

However, a small number of Aromanians do support these efforts. In 1998, the Greek President Costis Stephanopoulos visited Metsovo. He encouraged Aromanians to speak and teach their language so it would not be lost. Still, there are no schools or churches teaching or holding services in Aromanian today.

Many Aromanians see themselves as both Vlachs and Greeks. But a small group in remote villages in the Pindus mountains see themselves as completely separate from Greeks. In these areas, older generations still speak Aromanian and follow their own customs.

The debate continues with different views. Some Vlachs in Greece say they are happy with their dual identity. But some outside Greece point to cases like Sotiris Bletsas. He was arrested in Greece in 1995 for sharing materials about language minorities. He was first found guilty but later cleared.

See also

- Aromanian language

- Aromanian question

- Vlachs

Images for kids