History of the University of Notre Dame facts for kids

The University of Notre Dame is a famous university in Indiana, USA. It was started on November 26, 1842, by Father Edward Sorin. He was a priest from the Holy Cross group and was also the first president. At first, it was only for boys, built on land given by the local Catholic Bishop. Today, many Holy Cross priests still work at the university, including its president. Notre Dame became very well-known in the early 1900s because of its amazing Fighting Irish football team. A legendary coach named Knute Rockne helped them become famous. The university grew a lot between 1952 and 1987 under President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh. He made the university's programs and reputation much stronger. In 1972, women were first allowed to study there as regular students.

Contents

Starting the University

In 1839, the Bishop of Vincennes, Right Rev. Célestine Guynemer de la Hailandière, was worried. He saw that there wasn't enough Catholic education in his area. So, he asked Rev. Basil Moreau, the leader of the Congregation of Holy Cross, for help. He wanted a priest and four brothers to start a school.

Once enough money was collected, Father Moreau chose a young and energetic priest, Rev. Edward Sorin. Father Sorin left France on August 8, 1841, with six brothers. They traveled across the ocean and arrived in New York. After a few days, they set off for Indiana. They reached Bishop Hailandière in Vincennes on October 8.

The Bishop gave Father Sorin and his brothers a church and a farm in Montgomery, Indiana. Life on the farm was hard because they didn't have much money. The winter was also very harsh. The men were all French and not used to American farming. Father Sorin and the Bishop also had disagreements about money.

In early 1842, Father Sorin started thinking about building a college. There was already a college in Vincennes, but it didn't last long. Father Sorin first thought of building the college at St. Peter's. But the Bishop disagreed, saying it wasn't part of the original plan. However, the Bishop said he wouldn't mind a college elsewhere. He just wanted to make sure the brothers could still do their teaching duties.

Near the end of October 1842, the Bishop offered Father Sorin some land. This land was far away in northern Indiana, close to Michigan. It was a mostly unsettled area.

The Land's History

This land, about 524 acres, was bought between 1830 and 1832. It was purchased by Rev. Stephen Badin, who was the first priest ordained in the United States. He came to the area in 1830 to work with the Potawatomi tribe. Chief Leopold Pokagon had invited him.

Father Badin bought the land from the government and private owners. He was joined by Father Louis Deseille in 1833. They both served the Potawatomi community. These communities were important in resisting the forced removal of Native Americans in the 1830s.

In 1836, Father Badin sold the land to Simon Bruté and left the mission. Father Deseille died soon after. He was replaced by Benjamin Petit. Father Petit also opposed the removal of the Potawatomi. He joined them on the Trail of Death in 1838. This was a difficult forced march through Illinois and Missouri into Kansas. Father Petit became very ill from the march and died soon after.

After the Potawatomi left and Father Petit died, the land went back to the Bishop. In 1840, the Bishop offered it to another priest, Ferdinand Bach. He hoped Bach would build a college there, as Father Badin had wanted. Bach bought more land, but then decided he couldn't do the project. So, he returned everything to the Bishop. That's how, in 1842, the Bishop offered the 524 acres to Father Sorin.

After thinking it over with the brothers, Father Sorin accepted the land. The Bishop's condition was that he had to start a college within two years.

Arriving at Notre Dame

On November 16, Father Edward Sorin traveled to the chosen site. He was with seven Holy Cross brothers. The rest of the group stayed at St. Peter's to continue teaching. This was as promised to the Bishop.

Only two of the seven brothers had come from France with Sorin. The other five had joined them in Indiana. On the afternoon of November 26, 1842, Sorin arrived in South Bend. At that time, South Bend was just a small village. He went to the home of Alexis Coquillard, a French-American trapper.

That same afternoon, Father Sorin and the Brothers went to see the land. It was covered in snow, making the winter forest look softer. The only buildings on the land were Father Stephen Badin's old Log Chapel. This chapel had been used for Native American missions and as a church for local Catholics. There was also a house for an interpreter named Charron and his wife, and a small shed.

Father Sorin wrote a joyful letter about their arrival to his leader, Rev. Basil Moreau. He said:

Everything was frozen, and yet it all appeared so beautiful. The lake, particularly, with its mantle of snow, resplendent in its whiteness, was to us a symbol of the stainless purity of Our August Lady, whose name it bears; and also of the purity of soul which should characterize the new inhabitants of these beautiful shores. Our lodgings appeared to us-as indeed they are-but little different from those at St. Peter's. We made haste to inspect all the various sites on the banks of the lake which had been so highly praised. Yes, like little children, in spite of the cold, we went from one extremity to the other, perfectly enchanted with the marvelous beauties of our new abode. Oh! may this new Eden be ever the home of innocence and virtue!

The next day, November 27, they officially took possession of the land. This is why there's some confusion about the exact founding date of Notre Dame. Both November 26 and 27 have been mentioned as the official date.

Early Years and Growth

Father Sorin and his brothers faced a big challenge. They had very little money, about $370. They needed to serve the local Native American tribes and the few white Catholic families. At the same time, they had to start a college within two years.

St. Joseph County was small back then, with only about 6,500 to 7,500 people. South Bend had less than 1,000 residents. There were only about twenty Catholic families, and people in the area were often against Catholics.

Sorin and his seven brothers traveled 250 miles north during a very harsh winter. They arrived in South Bend on November 26, 1842. They were welcomed by Alexis Coquillard. The next day, they officially took over the property.

First Buildings and Challenges

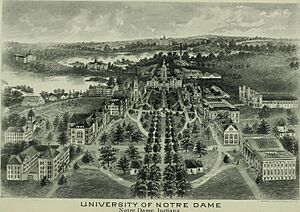

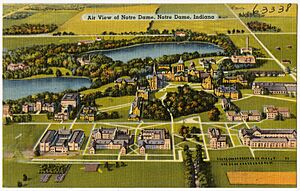

The property had only three buildings: a log chapel, a small two-story house, and a shed. Only 10 of the 524 acres were cleared for farming. Sorin noted that the soil was good for growing wheat and corn. The land had two small lakes. The snow and marshy areas might have made it look like one big lake to Sorin. This is why he named the mission "Notre Dame du Lac," meaning "Our Lady of the Lake."

Their most urgent need was warm places to live for themselves and for the brothers still in St. Peter's. They decided to build a second log cabin. Since they had no money, they asked the people of South Bend for donations or help. With local support, they gathered timber and built the walls. Sorin and the brothers finished the roof and the cabin on March 19, 1843.

Sorin focused on building a proper college. This was the condition for getting the land from Bishop Hailandière. Sorin had planned for an architect to come and start building a main building. But the architect didn't show up. So, Sorin and the brothers built Old College. This was a two-story brick building used as a dormitory, bakery, and classrooms. It helped house the growing community.

More members of the Holy Cross group arrived from St. Peter's and France in 1843. Badin's log chapel became a carpenter's shed and home for the Brothers. The 1843 cabin became a chapel and home for the Sisters.

Opening the College

With Old College ready, the university officially opened in the fall of 1843. Five students enrolled at first, with seven more joining later. Sorin based the school on the French "collège" model. This combined two years of high school and four years of college.

The early classes focused on reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and geography. More advanced subjects were also taught, like Latin, Greek, French, mathematics, public speaking, botany, drawing, music, and zoology. Tuition was $100 per year for full-time students. Orphans also received an education. They learned manual trades like carpentry and farming from the Brothers. By the 1844–1845 school year, about 40 students were attending.

In August 1843, the architect finally arrived. Sorin then started building the first Main Building. It was completed in 1844 and made larger in 1853. This building was the entire college until a bigger Main Building was built in 1865.

Notre Dame started as a primary and secondary school. But it quickly received its official college charter from the Indiana General Assembly on January 15, 1844. The school was officially named the University of Notre Dame du Lac. This means University of Our Lady of the Lake.

Even though Notre Dame was only for boys, the all-girls Saint Mary's College was founded nearby in 1844. More students came to Notre Dame, and the first degrees were given out in 1849. The university also added new buildings for students and teachers to live, study, and eat.

Overcoming Challenges

Notre Dame faced many difficulties in its early years. Fires were common and caused a lot of damage. In 1849, a school for manual labor was completely destroyed. In 1855, the original log cabins burned down.

A nearby farmer built a dam that caused water to back up. This created a swampy area around the Notre Dame lakes. This swamp led to outbreaks of diseases like malaria and cholera. Father Sorin believed the swamp was the cause. In 1855, after two more deaths from disease, Sorin convinced the farmer to sell him the land with the dam. But the farmer left before finishing the deal. Angry, Sorin sent brothers to tear down the dam by hand. The farmer quickly completed the sale. The marsh was drained, the land dried up, and the diseases disappeared.

In 1857, Rev. Basil Moreau, the founder of the Holy Cross group, visited Notre Dame. With each new president, new academic programs were offered. New buildings were also constructed. The first Main Building was replaced by a larger one in 1865. This new building held the university's offices, classrooms, and dorms. In 1873, a library collection was started. By 1879, it had 10,000 books.

The university's charter was updated by the Indiana General Assembly on March 8, 1873.

The Great Fire of 1879

On April 23, 1879, the entire Main Building, including its library, was destroyed by a fire. Luckily, the nearby church was saved. The school closed right away, and students were sent home.

The library collection was rebuilt and placed in the new Main Building. Around the time of the fire, a Music Hall opened. This hall, later called Washington Hall, hosted plays and musical shows.

After the fire, William Corby, who was the university's president, promised that Notre Dame would reopen for the fall semester. Father Sorin was determined to rebuild and continue the university's growth. It is said that the 65-year-old Sorin walked around the ruins. He looked determined and told everyone to go into the church with him.

Growing Stronger

The presidency of Thomas E. Walsh (1881–1893) focused on making Notre Dame's academics better. Many students came for business courses and didn't graduate. He started a "Belles Lettres" program. He also invited important thinkers like Maurice Francis Egan to campus.

Washington Hall was built in 1881 as a theater. The Science Hall (now LaFortune Student Center) was built in 1883 for science programs and labs. Sorin Hall was the first dorm on campus with private rooms for students. This was a new idea at the time.

During Walsh's time, Notre Dame started its football program. The Law School, founded in 1869, was reorganized. Its new building was later named after William J. Hoynes, who led the Law School for many years.

Rev. John Augustine Zahm was in charge of the Holy Cross group in the U.S. from 1898 to 1906. He wanted to modernize Notre Dame. He built new buildings and added to the art gallery and library. He also pushed for Notre Dame to become a research university. However, his leaders thought he was expanding too quickly and causing too much debt.

Andrew Morrissey, president from 1893 to 1905, wanted to keep the school smaller. During his time, the Grotto was built. More additions were made to Sorin Hall, and the first gymnasium was built. By 1900, over 700 students were enrolled.

The idea of becoming a research university was later supported by John W. Cavanaugh. He improved educational standards. He attracted many smart scholars and added new courses like chemical engineering. During his presidency, Notre Dame also became a strong force in football. In 1917, Notre Dame gave its first degree to a woman. However, many female students didn't attend until 1972.

James A. Burns became president in 1919. He continued Cavanaugh's work and made big academic changes. He adopted an "elective system," allowing students more choice in their classes. This helped the school meet national standards. Notre Dame continued to grow, adding more colleges and programs. By 1921, with the addition of the College of Commerce, Notre Dame had five colleges and a law school.

On October 15, 1919, Éamon de Valera, an important Irish leader, visited Notre Dame. He spoke in Washington Hall about Ireland's cause. He said it was "the happiest day since coming to America."

Between the World Wars

Notre Dame kept growing, adding more colleges, programs, and sports teams. By 1921, it had grown from a small college to a university with five colleges and a professional law school. The university continued to expand with new dorms and buildings under each president.

Knute Rockne and Football Success

Knute Rockne became the head football coach in 1918. Under his leadership, the Notre Dame team had an amazing record. They won 105 games, lost only 12, and tied 5 times. In his 13 years, the team won three national championships. They also had five seasons where they didn't lose any games. They won the Rose Bowl in 1925. Famous players like George Gipp and the "Four Horsemen" played for him. Knute Rockne has the highest winning percentage in college football history.

Rockne's last game as coach was on December 14, 1930. He led a team of Notre Dame all-stars against the New York Giants. This game raised money for unemployed and needy people in New York City.

The success of Notre Dame football showed the growing importance of Irish Americans and Catholics in the 1920s. Catholics cheered for the team, especially when they beat schools that represented the Protestant establishment. Because Notre Dame was a leading Catholic institution, it sometimes faced anti-Catholic feelings.

Presidents O'Donnell and O'Hara

Charles L. O'Donnell (1928–1934) and John Francis O'Hara (1934–1939) helped the university grow in size and academics. They brought many famous thinkers and writers to campus. O'Hara also focused on expanding the graduate school.

New buildings included Notre Dame Stadium, the law school building, and the Rockne Memorial. Many new dorms and engineering buildings were also built. This fast growth cost over $2.8 million. Much of this money came from football earnings. O'Hara strongly believed that the Fighting Irish football team could show the public Notre Dame's ideals. He said, "Notre Dame football is a spiritual service because it is played for the honor and glory of God and of his Blessed Mother."

World War II Impact

World War II was a very important time for the university. Before the United States joined the war, the campus had 3,500 students. Only a few military programs existed. But everything changed after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered the war. Many students joined the military, and enrollment dropped to only 750 students. This caused a big loss of money for the university. Donations from alumni also stopped. Father Hesburgh said the university was in danger of closing.

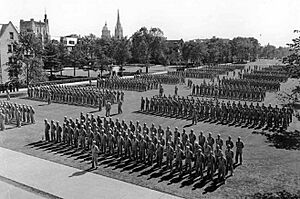

The situation improved when President Hugh O’Donnell offered Notre Dame's facilities to the Navy. In January 1942, the Navy decided to start a training program at Notre Dame. About 1,200 officer trainees arrived in April 1942. They lived in dorms, ate in the South Dining Hall, and took classes. By the time the program ended in November 1945, over 10,000 officers had graduated.

Starting in July 1943, Notre Dame also hosted another Navy training program. Trainees took classes with Notre Dame professors. Between these programs, more than 25,000 Navy officers trained at Notre Dame from 1941 to 1946. These programs increased the student population to 3,500-4,000. This kept Notre Dame financially stable during the war. Because of this, Notre Dame is sometimes called "Annapolis West." As a thank you, Father Hesburgh promised to keep the Naval Academy on the football schedule forever. The yearly Notre Dame-Navy football game is still a special tradition.

Post-War Years

After the war, President John J. Cavanaugh (1946–1952) worked to improve academic standards. He also reorganized the university's management. Student enrollment quadrupled, and graduate student enrollment grew five times. Cavanaugh also established new research institutes. He oversaw the construction of new science halls, dorms, and the Hall of Liberal Arts. This was made possible by a large donation. He also created advisory councils, which are still important for the university today.

The Hesburgh Era: 1952–1987

Rev. Theodore Hesburgh was president for 35 years (1952–1987). During his time, the university changed dramatically. The yearly budget grew 18 times larger. The university's savings grew 40 times larger. Research funding increased 20 times. Student enrollment almost doubled, and the number of teachers more than doubled. The number of degrees given out each year also doubled.

On October 18, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Notre Dame. He talked about segregation, discrimination, and the civil rights movement. The event was organized by Hesburgh and attracted a large, diverse crowd of 3,000 to 3,500 people.

Welcoming Women Students

In the mid-1960s, Notre Dame and Saint Mary's College started a program. Students could take classes not offered at their own school. This brought more women to Notre Dame, where some women were already in graduate programs.

University leaders explained that having both male and female students was becoming normal. It also allowed Notre Dame to attract more very bright students. Two of the male dorms were changed to house the new female students in the first year. The first female student to transfer from St. Mary's College graduated in 1972 with a bachelor's degree in marketing.

Modern Era

Malloy Era: 1987–2005

Under President Edward Malloy (1987–2005), Notre Dame's reputation, faculty, and resources grew quickly. He added over 500 professors. The academic quality of students improved greatly. The number of minority students more than doubled. The university's savings grew from $350 million to over $3 billion. The yearly budget rose to over $650 million. Research funding also increased. Notre Dame's most recent fundraising campaign raised $1.1 billion. This was the largest in the history of Catholic higher education.

Jenkins Era: 2005–Present

Currently, Notre Dame is led by Rev. John I. Jenkins. He became the 17th president on July 1, 2005. In his first speech, Jenkins said he wanted the university to be a leader in research. He also wanted to connect faith with studies.

COVID-19 Pandemic Impact

Since early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected Notre Dame. On February 28, 2020, the university stopped its study abroad program in Rome. On March 11, 2020, Notre Dame announced it would stop all in-person classes. Online classes began on March 23, 2020.

In May 2020, the university said in-person classes would restart in Fall 2020. Notre Dame resumed in-person teaching in August 2020. It briefly stopped later that month due to a rise in cases. But it returned to in-person classes by early September.

The Fall 2020 semester had many changes. The Notre Dame Fighting Irish football team joined the Atlantic Coast Conference for that season. Students returned to school two weeks early and did not have their usual fall break. The university put in place mandatory testing, contact tracing, and quarantine rules.

In October 2020, President Jenkins tested positive for COVID-19. He had attended a White House ceremony without wearing a mask. This led to mixed reactions from students and teachers.

Students felt a lot of stress during the fall semester. A survey showed that over two out of five students felt moderate to severe stress. By the end of Fall 2020, 15% of undergraduate students at Notre Dame had been diagnosed with COVID-19.

In Spring 2021, Notre Dame continued in-person classes. Large student gatherings were a challenge. In March 2021, Notre Dame announced it had enough vaccine doses. This meant all students could be vaccinated before the end of the semester.

University Presidents

The President of the University of Notre Dame is the leader of the university. They are chosen by the Board of Trustees.

The president must be a priest from the Congregation of Holy Cross. The first president was the university's founder, Rev. Edward Sorin. Many presidents have also been alumni or professors at the university.

- Edward Sorin, C.S.C. (1842–1865)

- Patrick Dillon, C.S.C. (1865–1866)

- William Corby, C.S.C. (1866–1872 and 1877–1881)

- Auguste Lemmonier, C.S.C. (1872–1874)

- Patrick Colovin, C.S.C. (1874–1877)

- Thomas E. Walsh, C.S.C. (1881–1893)

- Andrew Morrissey, C.S.C. (1893–1905)

- John W. Cavanaugh, C.S.C. (1905–1919)

- James A. Burns, C.S.C. (1919–1922)

- Matthew J. Walsh, C.S.C. (1922–1928)

- Charles L. O’Donnell, C.S.C. (1928–1934)

- John Francis O’Hara, C.S.C. (1934–1940)

- Hugh O’Donnell, C.S.C. (1940–1946)

- John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C. (1946–1952)

- Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. (1952–1987)

- Edward Malloy, C.S.C. (1987–2005)

- John I. Jenkins, C.S.C. (2005–2024)

- Robert A. Dowd, C.S.C. (2024-present)

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |