Potawatomi Trail of Death facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Potawatomi Trail of Death |

|

|---|---|

| Part of Indian removal | |

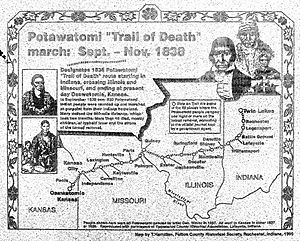

Map of the trail route: The tribe traveled from Twin Lakes, Indiana, arriving in Osawatomie, Kansas two months later.

|

|

| Location | United States |

| Date | September 4 - November 4, 1838 |

| Target | Potawatomi |

|

Attack type

|

Population transfer, Ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | 40+ |

| Assailants | United States |

| Motive | Expansionism |

The Potawatomi Trail of Death was a sad and difficult journey in 1838. About 859 members of the Potawatomi nation were forced by soldiers to leave their homes in Indiana. They had to move to new lands in what is now eastern Kansas.

The long march started at Twin Lakes, Indiana (near Plymouth, Indiana) on September 4, 1838. It ended near Osawatomie, Kansas, two months later. The journey was about 660 miles (1,062 km) long and took 61 days. Sadly, more than 40 people died along the way, most of them children. This was the largest forced relocation of Native Americans in Indiana's history.

The Potawatomi had given up their lands in Indiana to the government through several agreements between 1818 and 1837. However, Chief Menominee and his group at Twin Lakes refused to leave. Even after the deadline of August 5, 1838, they stayed. The Indiana governor, David Wallace, told General John Tipton to gather a local group of 100 volunteers. Their job was to make the Potawatomi leave the state.

On August 30, 1838, Tipton's group arrived unexpectedly at Twin Lakes. They surrounded the village and gathered the Potawatomi for their move to Kansas. Father Benjamin Marie Petit, a Catholic missionary, joined his people on this hard journey. They traveled from Indiana, across Illinois and Missouri, into Kansas. There, the Potawatomi were placed under the care of Father Christian Hoecken at Saint Mary's Sugar Creek Mission. This was the true end point of their march.

A historian named Jacob Piatt Dunn first called this event "The Trail of Death" in his 1909 book, True Indian Stories. In 1994, the states of Indiana, Illinois, and Kansas declared it a Regional Historic Trail. Missouri did the same in 1996. By 2013, there were 80 markers along the route. These markers are placed every 15 to 20 miles, showing where the group camped each day. Special highway signs in Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas also mark the path.

Contents

Why the Potawatomi Were Forced to Move

The Potawatomi are a group of people who speak the Algonquian language. They used to live in areas from northern Wisconsin and Michigan down to Lake Erie. This included parts of northern Illinois, north central Indiana, and southern Michigan. Even though the Miami people had lived in Indiana for a long time, the Potawatomi were also seen as traditional owners of the land.

Agreements and Land Changes

During the War of 1812, the Potawatomi sided with the British. They hoped to stop American settlers from moving onto their lands. After the war, they lived peacefully with their white neighbors. Around 1817, about 2,000 Potawatomi lived along rivers and lakes in northern Indiana. At this time, the state and federal governments wanted to open up northern Indiana for European American settlers.

Through several agreements with the U.S. government between 1818 and 1828, the Potawatomi gave up large parts of their land in Indiana. In return, they received yearly payments, goods, and some reservation lands within the state. Some tribal members also received their own pieces of land in northern Indiana.

The Indian Removal Act

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act was passed. This law allowed the government to offer land in the West to Native American tribes. In exchange, the government would buy their lands east of the Mississippi River. The main goal of this act was to make Native American tribes in the East move to lands west of the Mississippi River. Other tribes already lived in those western areas. This law especially targeted the Five Civilized Tribes in the Southeast. It was also used for other tribes living east of the Mississippi, including some near the Great Lakes.

In October 1832, the Potawatomi signed three more agreements. These agreements, made near the Tippecanoe River in Indiana, gave the government most of their remaining lands in northwestern and north central Indiana. They received payments, small reservation lands in Indiana, and some land for individuals. The government also agreed to help the Potawatomi if they decided to move. These agreements reduced the Potawatomi's reservation lands in Indiana, including land along the Yellow River.

Chief Menominee's Resistance

One agreement, signed on October 26, 1832, set up Potawatomi reservation lands within Indiana and Illinois. This was for groups led by chiefs like Menominee. Chief Menominee's group at Twin Lakes, Indiana, would later be forced to leave these lands in 1838.

More pressure from government negotiators, especially Colonel Abel C. Pepper, led to more agreements. From 1834 to 1837, the Potawatomi gave up all their remaining reservation lands in Indiana. In 1836 alone, they signed nine agreements. These were sometimes called the "Whiskey Treaties" because whiskey was given to encourage signatures. Under these agreements, the Potawatomi agreed to sell their Indiana land and move west within two years.

A key agreement that led to the forced move from Twin Lakes was made at Yellow River on August 5, 1836. Under this agreement, the Menominee Reserve was given to the government. The Potawatomi agreed to move west of the Mississippi River within two years. In return, they would get $14,080 for their 14,080 acres of land, after debts were paid.

However, Chief Menominee and seventeen members of his group refused to be part of these talks. They did not believe the agreement was valid for their land. On November 4, 1837, Chief Menominee and other Potawatomi sent a formal protest to General John Tipton. They claimed their signatures on the 1836 agreement were fake, or that people who didn't represent the tribe had signed. There was no record of a reply. They also sent protests to President Martin Van Buren and Secretary of War Lewis Cass, but the government did not change its mind.

By 1837, some Potawatomi groups had already moved peacefully to their new lands in Kansas. By August 5, 1838, the deadline to leave Indiana, most Potawatomi had gone. But Chief Menominee and his group at Twin Lakes still refused. The next day, Colonel Pepper held a meeting at Menominee's village. He explained that the Potawatomi had given up their land and had to move. Chief Menominee replied through an interpreter:

My brother, the President is fair, but he listens to young chiefs who have lied. When he knows the truth, he will leave me alone. I have not sold my lands. I will not sell them. I have not signed any agreement, and will not sign any. I am not going to leave my lands, and I do not want to hear anything more about it.

After this meeting, tensions grew between the Potawatomi and white settlers who wanted the land. Some settlers worried about violence and asked Indiana governor David Wallace for protection. Governor Wallace then told General John Tipton to gather 100 volunteers to force the Potawatomi off their land.

Reverend Louis Deseille, a Catholic missionary at Twin Lakes, said the 1836 Yellow River agreement was a trick. He argued that "this band of Indians believe that they have not sold their reservation and that it will remain theirs as long as they live and their children." Because he supported the Potawatomi, Colonel Pepper ordered Father Deseille to leave the mission. Father Deseille went to South Bend, Indiana, but died there on September 26, 1837. His replacement, Reverend Benjamin Marie Petit, arrived in November 1837. After a few months, Father Petit accepted that the Potawatomi would be forced to move. He received permission to join his people on their difficult march to Kansas in 1838.

The Forced Relocation Begins

On August 30, 1838, General Tipton and his volunteer soldiers arrived unexpectedly at the Potawatomi village at Twin Lakes. An elderly woman, Makkahtahmoway, Chief Black Wolf's mother, was so scared by the soldiers' gunshots that she hid in the woods for six days. She had an injured foot and couldn't walk. Another Native American found her and brought her to South Bend.

When Tipton arrived, he reportedly called a meeting at the village chapel. He held the Potawatomi chiefs so they couldn't leave. Father Petit, who was in South Bend at the time, later said that the Potawatomi were taken by surprise. Tipton reported that some Potawatomi were already near the chapel when he arrived. But he admitted they were not allowed to leave until they agreed to give up their land.

Between August 30 and September 3, 1838, Tipton's soldiers surrounded Menominee's village. They gathered the remaining Potawatomi and prepared for their move to Kansas. The names of 859 Potawatomi family heads and individuals were recorded. The soldiers also burned the crops and destroyed about 100 structures in the Potawatomi village. This was done to stop them from trying to return. Father Petit closed the mission church. He wrote to his family on September 14, 1838, "It is sad, I assure you, for a missionary to see a young and vigorous work expire in his arms."

The Difficult Journey West

The journey from Twin Lakes, Indiana, to Osawatomie, Kansas, began on September 4, 1838. It covered about 660 miles (1,062 km) over 61 days. Conditions were often hot, dry, and dusty. The group of 859 Potawatomi also included 286 horses, 26 wagons, and 100 armed soldiers. During the trip to Kansas, 42 people died, 28 of them children. This was the largest forced Native American relocation in Indiana's history.

Journals, letters, and newspaper stories from that time describe the route, weather, and living conditions. People who were there, like John Tipton, Father Petit, and Judge William Polke, wrote about their daily experiences. Tipton led the soldiers as the group's escort. Judge Polke, from Rochester, Indiana, was the government agent in charge of the group. Father Petit held religious services and cared for the sick and dying. A doctor, Dr. Jerolaman, joined the group in Logansport, Indiana. Other local doctors sometimes visited the camps.

The March Across States

On September 4, the march to Kansas began. Three chiefs, Menominee, Makkatahmoway (Black Wolf), and Pepinawa, were treated as prisoners. They were forced to ride in a wagon with armed guards. Father Petit managed to get them released from the wagon in Danville, Illinois, after promising they wouldn't try to escape.

Father Petit later described the group's march in a letter on November 13, 1838:

The order of march was as follows: the United States flag, carried by a soldier; then one of the main officers, next the baggage carts, then the carriage, which was used for the Indian chiefs. Then one or two chiefs on horseback led a line of 250 to 300 horses ridden by men, women, and children in a single line. On the sides of the line were the soldiers, hurrying those who fell behind, often with harsh words. After this group came 40 baggage wagons filled with luggage and Native Americans. The sick were lying in them, roughly shaken, under a canvas which, far from protecting them from dust and heat, only kept air away from them. Several died this way.

Early Days in Indiana

On the first day, September 4, 1838, the group traveled 21 miles (34 km). They camped at Chippeway village on the Tippecanoe River, north of Rochester. They camped for a mile around William Polke's house. On the second day, 51 sick people were left behind at Chippeway. The group marched single file down Rochester's Main Street, with soldiers watching them. A ten-year-old boy, William Ward, followed them, wanting to go with his friends, but his mother brought him home. They reached Mud Creek in Fulton County, where an infant died. This was the first death of the journey.

By the third day, September 6, they reached Logansport, Indiana. The camp was described as "a scene of sadness; on all sides were the sick and dying." The group stayed in Logansport until September 9. About 50 sick and elderly people, along with their caregivers, were left there to recover. Most were well enough to rejoin the group in a few days. During this part of the journey, the group traveled along the Michigan Road. On September 10, the march continued from Logansport. They traveled along the north side of the Wabash River, passing through Pittsburg, Battle Ground, and Lafayette. They reached Williamsport, Indiana, on September 14. Two or more people died almost every day. Their last camp in Indiana was by a "dirty-looking stream" near the Indiana-Illinois state line.

Journey Through Illinois and Missouri

On September 16, the group entered Illinois and camped at Danville. Four more Potawatomi died there and were buried. Father Petit joined the group at Danville and traveled with them to Kansas. He cared for the sick and helped with their religious needs. Tipton wrote that Father Petit "made a very good change in the behavior and hard work of the Indians." Father Petit described his arrival:

On Sunday, September 16, I saw my Christians, under a hot midday sun, in clouds of dust, marching in a line, surrounded by soldiers who were rushing them.... Nearly all the children, weak from the heat, had become completely tired and sad. I baptized several who were newly born – happy Christians, who with their first step passed from earthly exile to the heavenly home."

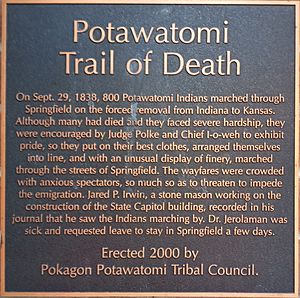

After Danville, the group traveled 6 miles (10 km) to Sandusky Point (now Catlin, Illinois). They rested there from September 17 to 20. On September 20, General Tipton left fifteen soldiers with the group and returned to Indiana. Judge Polke then led the Potawatomi the rest of the way to their new land. Between September 20 and October 10, the Potawatomi traveled through the Illinois prairie. They passed through towns like Monticello, Decatur, and Springfield. They crossed the Illinois River by ferry at Naples. On October 10, the group left Illinois and crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri on steam-powered ferry boats from Quincy, Illinois.

According to Father Petit, "After arriving in Missouri, we hardly had any sick." The Native Americans were allowed to hunt for wild animals to add to their food. As they marched through Missouri, the Potawatomi passed through many towns, including Palmyra, Paris, and Lexington. At Lexington, they crossed the Missouri River.

Arrival in Kansas

On November 2, the group crossed the north fork of the Blue River into Kansas. They camped at Oak Grove. On November 3, they reached Bull Creek, near Bulltown (now Paola, Kansas). The group finally reached the end of their journey on the western bank of the Osage River, at Osawatomie, Kansas, on November 4, 1838.

After traveling 660 miles (1,062 km), the Potawatomi were placed under the care of the local Native American agent and Reverend Christian Hoecken. Out of the 859 people who started the journey, 756 Potawatomi survived. 42 were recorded as having died, and the rest escaped.

Judge Polke and the soldiers who went with the Potawatomi to Kansas began their return trip to Indiana on November 7–8, 1838. Father Petit, who was very weak from the hard journey, started his return trip to Indiana on January 2, 1839. He was too ill to continue and died in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 10, 1839, at age 27. His death was partly due to the difficulties of the journey.

Life After the Trail

The Potawatomi, also known as the Mission Band, stayed in eastern Kansas for ten years. In March 1839, they moved about 20 miles (32 km) south to the Sugar Creek mission in Linn County, Kansas. In 1840, more Potawatomi from Indiana arrived to settle on the Kansas reservation. The next year, on April 15, 1841, Chief Menominee died and was buried in Kansas. He never returned to Indiana.

In 1848, the Potawatomi moved further west to St. Marys, Kansas, about 140 miles (225 km) northwest of Sugar Creek. They stayed there until the Civil War. In 1861, the Potawatomi of the Woods Mission Band were offered a new agreement. This agreement gave them land in Oklahoma. Those who signed this agreement became Citizen Band Potawatomi because they were given U.S. citizenship. Their main office today is in Shawnee, Oklahoma. After the Civil War, the Potawatomi spread out. Many moved to other reservations in Kansas and Oklahoma. A reservation for the Prairie Band Potawatomi is in Mayetta, Kansas. The state of Kansas named Pottawatomie County, Kansas, after the tribe.

Not all Potawatomi from Indiana moved to the western United States. Some stayed in the East, while others went to Michigan. There, they became part of the Huron and Pokagon Potawatomi groups. A small group joined about 2,500 Potawatomi in Canada.

Remembering the Trail

In the years since 1838, many groups have placed special markers along the route. These markers honor those who marched to Kansas and remember those who died. In 1994, the Trail of Death was named a Regional Historic Trail by the states of Indiana, Illinois, and Kansas. Missouri did the same in 1996. By 2003, there were 74 markers along the route.

Key Locations and Markers

- Twin Lakes, Indiana: The march began here on September 4, 1838.

- A statue of Chief Menominee was put up in 1909 near Twin Lakes. It was the first statue to a Native American built because of a state or federal law.

- A large rock with a metal plaque marks the site of the Potawatomi's log chapel and village. This marker was dedicated in 1909.

- Rochester, Indiana: On September 4, 1838, the Potawatomi passed through Chippeway village, north of Rochester. About 50 very sick people were left here. On September 5, they marched down Rochester's Main Street.

- A large rock with a metal plaque was put up in 1922 by the Daughters of American Revolution.

- A memorial to Father Benjamin Petit is at the Fulton County Museum in Rochester.

- Logansport, Indiana: From September 6 to 9, the group camped near Logansport. Many were sick, and four children died.

- A historical marker for the Potawatomi camp was placed in 1988 at Logansport Memorial Hospital.

- Battle Ground, Indiana: The group camped west of Battle Ground on September 12.

- A plaque and map on a large rock at the Tippecanoe Battlefield Museum were placed by Girl Scout Troop 219 in 1996.

- Lafayette, Indiana: The group traveled west past Lafayette and camped near LaGrange on September 13, 1838.

- A metal plaque on a large rock marks the campsite at LaGrange, a village that no longer exists.

- Danville, Illinois: On September 16, 1838, the group camped near the Indiana-Illinois state line. Two small children died.

- A Trail of Death marker was placed in Ellsworth Park.

- Catlin, Illinois: (known as Sandusky Point in 1838) On September 17, the group traveled 6 miles (10 km) to Sandusky Point, where they stayed until September 20.

- A marker is on the grounds of the Catlin Historical Museum.

- Springfield, Illinois: The Potawatomi men were promised tobacco if they looked good walking through Springfield. Two children died overnight here.

- A marker on Oak Crest Road was put up by the Springfield chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1995.

- Jacksonville, Illinois: On October 1, 1838, they reached Jacksonville. A child fell from a wagon and was badly hurt.

- A Trail of Death marker is in Foreman Grove Park.

- Naples, Illinois: From October 3 to 4, the group spent 9 hours crossing the Illinois River by ferry. Two children died while they were camped across the river from Naples.

- Quincy, Illinois: For three days (October 8-10), the group camped near Quincy. They crossed the Mississippi River on a steam-powered ferry to Missouri. Three children died here.

- A marker was dedicated in Quincy's Quinsippi Island Park on September 15, 2003.

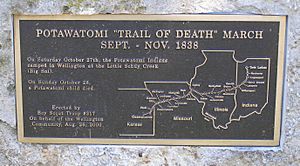

- Wellington, Missouri:

- A Trail of Death marker was placed in the town square by a local Boy Scout troop in 2000.

- Osawatomie, Kansas: The journey ended here on November 4, 1838.

- A marker honoring Father Benjamin Petit is at St. Philippine Duchesne Park, the site of the Potawatomi's Sugar Creek Mission. It was dedicated on September 28, 2003.

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |