Homer Plessy facts for kids

Homer Adolph Plessy (born Homère Patris Plessy; March 17, 1863 – March 1, 1925) was an American shoemaker and activist. He is best known for his role in the important U.S. Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson. Plessy purposely broke a Louisiana law about racial segregation to create a test case. He wanted the Supreme Court to decide if these segregation laws were fair under the U.S. Constitution.

The Court decided against Plessy. This ruling created the "separate but equal" rule. It meant that states could have separate facilities for black and white people, as long as they were supposedly "equal." This rule allowed Jim Crow laws to continue for many years. It wasn't until 1954, with the Brown v. Board of Education case, that the Supreme Court began to overturn this idea.

Plessy was born a free person of color into a French-speaking Creole family. He grew up after the Civil War, when black children could go to integrated schools, black men could vote, and mixed-race marriages were legal. However, many of these rights were lost after 1877. In the 1880s, Plessy became involved in fighting for civil rights. In 1892, a group called the Comité des Citoyens asked him to challenge Louisiana's Separate Car Act. This law said black and white people had to use separate train cars.

On June 7, 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket for a "whites only" train car. He boarded the train and was arrested by a detective hired by the group. A judge named John Howard Ferguson ruled against Plessy. He said Louisiana had the right to control railroads within its borders. Plessy appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Four years later, in 1896, the Court ruled 7–1 against Plessy. This decision established the "separate but equal" rule, which supported Jim Crow laws until the 1950s and 1960s.

Contents

Homer Plessy's Early Life

Homer Plessy was born on March 17, 1863, in New Orleans, Louisiana. He was the second child in a French-speaking Creole family. His parents, Joseph Adolphe Plessy and Rosa Debergue, were both mixed-race free people of color. Many of his family members were skilled workers like blacksmiths, carpenters, and shoemakers.

Plessy's father died in 1869. In 1871, his mother married Victor M. Dupart, who worked for the U.S. Postal Service and was also a shoemaker. Plessy's stepfather was active in politics. He joined the Unification Movement of 1873, which worked for political equality and an end to discrimination.

Civil Rights in Louisiana

Plessy grew up during a time when black people in Louisiana had gained many new rights. Starting in 1868, black men could vote if they paid a poll tax. In 1869, the state started a racially integrated school system. Interracial marriage became legal in 1870. Also, more than 200 black men held elected positions in the 1870s.

However, many of these rights began to disappear after 1877. This was when U.S. federal troops left the former Confederacy. When white Democrats regained power, they cut funding for black public schools. The Louisiana Constitution of 1879 also ended integrated schools.

Plessy became a shoemaker, like his stepfather, and also a political activist. In the 1880s, he worked at a shoe-making business in New Orleans. In 1888, he married Louise Bordenave. They moved to Faubourg Tremé, a mixed-race neighborhood, in 1889.

His political involvement began in the 1880s. In 1887, he was vice-president of a group called the Justice, Protective, Educational, and Social Club. This group worked to improve public education in New Orleans. They wanted to make sure black schools received fair funding and had good teachers.

The Plessy v. Ferguson Case

Planning the Test Case

In 1890, Louisiana passed the Separate Car Act. This law required separate train cars for black and white people. A group of eighteen black, Creole, and white residents of New Orleans formed the Comité des Citoyens (Committee of Citizens). They wanted to challenge this law. Many members worked for The New Orleans Crusader, a black newspaper.

The group asked attorney Albion W. Tourgée for help. He agreed to take their test case to court. They wanted the courts to decide if Jim Crow laws were constitutional. Tourgée suggested finding a plaintiff who looked white but had some black ancestry. He hoped this would show how unclear the idea of "race" was under the law.

The group first chose Daniel Desdunes, a musician. On February 24, 1892, Desdunes bought a first-class ticket on a train going to Mobile, Alabama. He sat in a "whites only" car and was arrested. However, the case was dropped because the Separate Car Act didn't apply to trips between states.

So, the Comité des Citoyens needed to try again with a trip entirely within Louisiana. They chose Homer Plessy to be the plaintiff. The group contacted the East Louisiana Railroad, which was against the law. They also hired a private detective, Chris C. Cain, to arrest Plessy. This made sure Plessy would be charged with breaking the Separate Car Act.

On June 7, 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket for a train from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. He sat in the "whites only" car. The conductor told Plessy to move, but he refused. The conductor returned with Detective Cain. Cain and other passengers removed Plessy from the train. Plessy was arrested and taken to jail. The Comité des Citoyens quickly arranged for his release.

The Trial and Appeals

On October 28, 1892, Plessy appeared before Judge John Howard Ferguson. Plessy's lawyer, James Walker, argued that the Separate Car Act went against the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments. These amendments promised equal protection under the law. On November 18, Judge Ferguson ruled against Plessy. He said Louisiana had the right to control railroads within its state borders.

Walker then appealed to the Louisiana Supreme Court. In December 1892, this court supported Ferguson's ruling. Justice Charles Erasmus Fenner said that segregated schools had been found constitutional in Massachusetts in 1849. He noted that prejudice was not created by law and probably couldn't be changed by law.

Supreme Court Decision

On January 5, 1893, Plessy's lawyers asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. The Court agreed. Tourgée represented Plessy, with help from former Solicitor General Samuel F. Phillips. The case was heard on April 13, 1896.

Tourgée argued that Louisiana's law violated the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery. He also argued it violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment says no state can take away a citizen's rights or deny them "equal protection of the laws." Tourgée said segregation made black people feel inferior and gave them a second-class status.

On May 18, 1896, the Supreme Court ruled 7–1 against Plessy. The Court said Louisiana's train car segregation laws were constitutional. Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote the main opinion. He said the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to ensure legal equality, but not to stop social differences or force races to mix.

The Court also rejected Tourgée's idea that segregation made black Americans feel inferior. Justice Brown wrote that if segregation made black people feel inferior, it was "solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction on it." This meant the Court believed black people chose to see segregation as a sign of inferiority, rather than the law itself making them inferior.

Later Life and Legacy

After the Supreme Court ruling, Plessy's criminal trial continued in Louisiana. On February 11, 1897, he was found to have broken the Separate Car Act. He paid a $25 fine. The Comité des Citoyens group broke up soon after.

Homer Plessy later worked as a laborer, warehouseman, clerk, and insurance collector. He died on March 1, 1925. He was buried in Saint Louis Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans.

The Impact of Plessy v. Ferguson

The "Separate but Equal" rule from the Plessy case was a major part of American law for many years. It was finally overturned in 1954 by the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education. Later, the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation illegal. Even though the Plessy case was about trains, it became the legal basis for separate school systems for 58 years.

In 2009, Keith Plessy, a descendant of Homer Plessy, and Phoebe Ferguson, a descendant of Judge John Howard Ferguson, met. They created the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation. This foundation works to teach people about civil rights history.

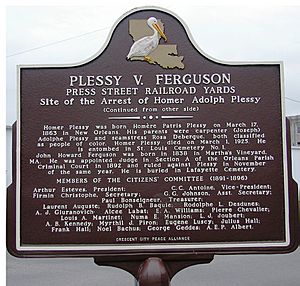

On February 12, 2009, a historical marker was placed in New Orleans where Homer Plessy was arrested in 1892. A part of Press Street was even renamed after Plessy in 2018.

On January 5, 2022, Homer Plessy received a pardon from John Bel Edwards, the Governor of Louisiana. This officially cleared him of his conviction.

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |