Honora Sneyd facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Honora Sneyd

|

|

|---|---|

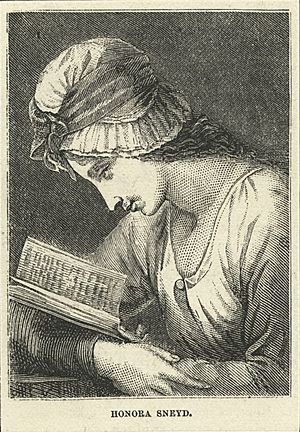

"Serena Reading", after George Romney

|

|

| Born | 1751 Bath, Somerset, Kingdom of Great Britain

|

| Died | 1 May 1780 (aged 28–29) Weston-under-Lizard, Staffordshire, Kingdom of Great Britain

|

| Resting place | Weston-under-Lizard, Staffordshire, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

Honora Edgeworth (born Honora Sneyd; 1751 – May 1, 1780) was an English writer and educator from the 1700s. She is known for her connections with famous writers and thinkers of her time, like Anna Seward and the Lunar Society. Honora also made important contributions to how children were educated.

She was born in Bath in 1751. After her mother passed away, she was raised by family friends, Canon Thomas Seward and his wife Elizabeth, in Lichfield, Staffordshire. There, she became very close friends with their daughter, Anna Seward.

Honora married Richard Edgeworth in 1773. She helped raise his children from his first marriage, including the famous writer Maria Edgeworth. Honora also had two children of her own. She worked with her husband to create new ideas for teaching children. These ideas led to books like Practical Education. Honora was also known for her strong beliefs about women's rights, especially about equality in marriage. She passed away in 1780 from tuberculosis.

Honora's Life Story

Early Years (1751–1773)

Honora Sneyd was born in Bath in 1751. She was the third daughter of Edward Sneyd and Susanna Cook. Her father was a soldier and had a job at the royal court. Honora was one of eight children. Her mother died in 1757 when Honora was only six years old. Her father found it hard to care for all his children. So, friends and family offered to help.

Living with the Seward Family (1756–1771)

Honora Sneyd moved in with family friends, Canon Thomas Seward and his wife Elizabeth. They lived in the Bishop's Palace in Lichfield, Staffordshire. The Sewards raised Honora as if she were their own child. She was like an adopted sister to their daughter, Anna Seward.

Anna Seward wrote about meeting Honora in her poem The Anniversary. Honora was first closer to Anna's younger sister, Sarah. But Sarah died in 1764 when Honora was thirteen. After Sarah's death, Anna became very close to Honora. Anna found comfort in her friendship with Honora. Honora's health was always delicate. She first showed signs of tuberculosis at fifteen, which later caused her death.

Honora's Education

In Lichfield, Honora Sneyd was taught by Canon Seward. He had modern ideas about female education. He even wrote a poem called The Female Right to Literature. Honora was described as smart and interested in science. From Anna, she also learned to love books and reading.

Honora was a talented student. She learned French and even translated a book by Rousseau for Anna. Canon Seward believed in educating girls, though not too freely. He taught them subjects like theology and math. They also learned to read, enjoy, write, and recite poetry. This was different from what girls usually learned back then.

The Seward home was a meeting place for many smart people. These included David Garrick, Erasmus Darwin, Samuel Johnson, and James Boswell. The children were encouraged to join in the conversations. This helped Honora learn even more.

Her Relationships

Honora Sneyd and Anna Seward lived together for thirteen years. They became very close friends. This friendship was important to Anna Seward's poems. Many people have discussed how close their friendship was.

Honora was known for being both smart and beautiful. Anna Seward and Richard Edgeworth both commented on this. When Honora was seventeen, she was briefly engaged to John André. Anna Seward had encouraged this relationship. However, their parents did not approve because of André's financial situation.

Around 1770, Thomas Day and Richard Edgeworth spent time at the Seward home. Both men were part of the Lunar Society. They both fell in love with Honora Sneyd. In 1771, Honora turned down Thomas Day's marriage proposal. Edgeworth said her letter was an "excellent answer" about men's rights. It also gave a "clear view of the rights of women."

Honora Sneyd had strong opinions about women's roles in marriage. She believed a husband should not control all of his wife's actions. She also thought that women did not need to stay hidden from society to be good wives. She wanted a marriage based on "reasonable equality." She told Day she would not change her life for his "dark and untried system."

In 1771, Honora's father moved to Lichfield. He brought his five daughters together there. Honora was nineteen. Anna was sad to see her friend leave. Thomas Day was upset by Honora's rejection. He then tried to marry Honora's younger sister, Elizabeth. But Elizabeth also said no.

Richard Edgeworth was very impressed by Honora. He wrote that her ideas were always fair. She spoke with "blushing modesty" but also with confidence. He found her graceful and beautiful. He felt she was the "picture of perfection." Edgeworth decided to move to France in 1771 to avoid his feelings for Honora.

Marriage to Richard Edgeworth (1773–1780)

Marriage and Move to Ireland (1773–1776)

Richard Edgeworth's first wife died in March 1773. She passed away ten days after giving birth to their fifth child. Edgeworth was in France at the time. When he heard the news, he went to London. He then went to Lichfield to propose to Honora Sneyd. She accepted right away.

Honora and Richard married at Lichfield Cathedral on July 17, 1773. Canon Thomas Seward performed the ceremony. Anna Seward was a bridesmaid. Soon after marrying, they moved to Edgeworthstown, Ireland. This was because of problems with Richard's family estates there.

Honora became a stepmother to Richard's four children. They ranged in age from seven months to nine years. These children included Maria Edgeworth, who later became a famous writer. Honora noticed that Maria, who was five, had some behavior issues. Honora believed in quick and firm discipline for children. She tried to apply this to the older children.

Maria Edgeworth was sent to boarding school in Derby in 1775. She later went to school in London after Honora died. Richard Edgeworth said the first two years were hard for Honora as a stepmother. Her relatives had even advised her not to take on the role.

Honora soon had her own children. Her daughter, Honora, was born in May 1774. She died at age sixteen. Her second child, Lovell, was born in June 1775. The Edgeworth children were raised using ideas from Rousseau, but changed by Honora and Richard.

Return to England (1776–1780)

After three years in Ireland, the family moved back to England in 1776. They settled in Northchurch, Hertfordshire. Honora and Anna Seward had stayed in touch through letters and visits.

In 1779, Honora Sneyd became ill with a fever. They consulted Erasmus Darwin, a famous doctor. He believed it was tuberculosis, which Honora had briefly had at age fifteen. He advised them not to return to Ireland. They sought advice from many doctors. But they only learned that her illness was incurable.

They eventually rented a house near Shifnal, Shropshire. This was closer to Honora's family and their friends. Honora made her will in April 1780.

Honora's Death

Honora Sneyd died from tuberculosis on May 1, 1780. She was at Bighterton, surrounded by her husband, her youngest sister Charlotte, and a servant. Honora was buried in the nearby Weston church. A plaque there remembers her life.

Honora Sneyd died within eight years of her marriage to Richard Edgeworth. She was about the same age as his first wife. The same disease had taken her mother's life. It would also take the life of her young daughter, Honora Edgeworth, and her younger sister, Elizabeth. At the time, people thought this was a weakness passed down in the family.

After Honora's death, Richard Edgeworth married her younger sister, Elizabeth Sneyd. He said this was Honora's dying wish. This marriage was seen as unusual by some. But it was done for the sake of the children.

Honora's Work

Practical Education Ideas

The Edgeworths worked together to create the idea of "Practical Education." This became a new way of thinking about teaching by the 1820s. Richard Edgeworth felt his first attempts to educate his eldest son had failed. So, he and Honora wanted to find better ways.

After their daughter Honora was born in 1774, the Edgeworths planned to write books for children. They were inspired by Anna Barbauld. Her book, Lessons for Children from two to three years old, was published in 1778. The Edgeworths used it with their daughters, Anna and Honora. They were amazed that the girls learned to read in six weeks.

Back in England, the Edgeworths were closer to the smart people of the Lunar Society. Richard and Honora decided to design a plan for their children's education. They read many books on childhood education. These included works by Locke, Hartley, and Priestley. Then, they watched how children behaved. They used these observations to create their own "practical" system.

Honora Sneyd started writing detailed notes about the Edgeworth children. These notes became the conversations in their final book. Richard and Maria Edgeworth said Honora believed education should be like a science experiment. She thought past failures were from following theory too much, not practice.

Honora and Richard applied new ideas from educational psychology to teaching. They saw that Barbauld's method worked because reading was made fun. Honora Sneyd came up with the title Practical Education for their work.

With her husband, Honora wrote the first version of Practical Education. It was a children's book called Practical education: or, the history of Harry and Lucy. It was started in 1778 and published in 1780. The book tells a simple story of parents and their two good children, Harry and Lucy. The children do chores and ask many questions. Their parents' answers teach them. The book showed nine ways of learning.

This book was meant to be part of a series. But the other parts were not written. The original plan was for many members of the Lunar Society to help. It was a big project to improve science and technical education. It also aimed to teach young children about morals and other subjects.

After Honora Sneyd's early death, her sister Elizabeth continued the work. She was Richard Edgeworth's third wife. The final version of the book was written by Richard and Maria Edgeworth. It was published in 1798. Maria later revised it as Early lessons. This project was a family effort that lasted over 50 years.

Richard Edgeworth noted that Honora was surprised that education theory had little proof. She wanted to use science to study child education. She kept a detailed record of children's reactions to new knowledge. She watched what questions children asked and how they solved problems. This work helped shape Richard Edgeworth's later writings on education. Honora Sneyd's ideas greatly influenced Maria Edgeworth's career as a children's writer.

Other Interests

Honora Sneyd was interested in science from an early age. This was because she met members of the Lunar Society. Richard Edgeworth was an inventor, and this interest drew him to her. After they married, she worked on his projects with him. He said she became an "excellent theoretic mechanick" herself.

Honora's Legacy

We mostly know about Honora Sneyd through the writings of others. These include Anna Seward and Richard Edgeworth. Honora Sneyd is often listed among the Bluestockings. These were educated upper-class women who valued learning over traditional female skills. They often formed close friendships with other women.

Her work on educational psychology was very important throughout the 1800s. Honora Sneyd's name is also linked to Anna Seward in discussions about female friendship.

Growing up with Canon Seward and the Lunar Society, Honora Sneyd and Anna Seward developed modern views on women's status. They believed in equality in marriage. Education for women was key to this. Honora married Richard Edgeworth believing they would be equal partners in his work. Anna and later Honora's stepdaughter, Maria Edgeworth, promoted these ideas. They were like early feminists in Britain. Today, Honora's stand on women's rights is remembered for her strong rejection of Thomas Day's ideas about the "perfect wife."

Anna Seward's will mentioned two pictures of Honora Sneyd. One was an engraving after George Romney, for which Honora had modeled as "Serena." The other was a small portrait drawn by John André. A special medallion of Honora was made by the Wedgwood factory in 1780. Honora Sneyd was the subject of many of Anna Seward's poems. Even after Honora married, Anna continued to write about her. Honora also appears as a character in a play about Major André and herself, called André; a Tragedy in Five Acts.

The plaque in St. Andrew's Church, Weston, where she is buried, reads: "In Memory of Honora, the second wife of Richard Lovell Edgeworth, Esq. of Edgeworthstown in Ireland. She was the daughter of Edward Sneyd, Esq. of Bishton in this county. She died on the 1st of May 1780, in the 29th year of her age. Her virtues and talents were equally distinguished. She was a woman of uncommon understanding, and of a most amiable disposition. Her life was a constant exercise of every social duty. Her death was a loss to all who knew her, and a source of deep sorrow to her family and friends. This monument is erected by her affectionate husband."

Images for kids

-

"Serena Reading", after George Romney

-

Anna Seward in 1799

-

Bishop's Palace, Lichfield

-

Richard Lovell Edgeworth in 1812

-

Maria Edgeworth in 1790

-

Jasper medallion of Honora Sneyd by Wedgwood in 1780, after an image by John Flaxman. Victoria and Albert Museum, London