Horace Silver facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horace Silver

|

|

|---|---|

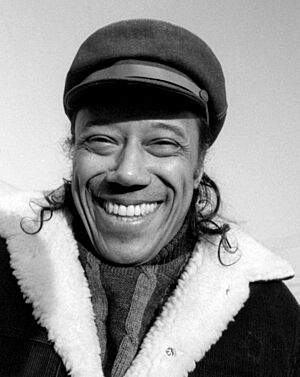

Silver by Dmitri Savitski, 1989

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | September 2, 1928 Norwalk, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | June 18, 2014 (aged 85) New Rochelle, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, hard bop, mainstream jazz, soul jazz, jazz fusion |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, arranger |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Years active | 1946–2004 |

| Labels | Blue Note, Silveto, Emerald, Columbia, Impulse!, Verve |

| Associated acts | Art Blakey, Junior Cook, Miles Davis, Art Farmer, Joe Henderson, Blue Mitchell, Hank Mobley |

Horace Ward Martin Tavares Silver (born September 2, 1928 – died June 18, 2014) was a famous American jazz musician. He was a talented pianist, composer, and arranger. He played a big role in creating the "hard bop" style of jazz in the 1950s.

Horace started playing the tenor saxophone and piano in school in Connecticut. His big chance came in 1950. A famous saxophonist named Stan Getz hired Horace's trio to tour with him. Soon, Horace moved to New York City. There, he became known for his unique bluesy piano playing and his original songs.

In the mid-1950s, he often played with other musicians. But his most important work was with the Jazz Messengers. He led this group with drummer Art Blakey. Their album Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers included Horace's first hit song, "The Preacher".

After leaving Blakey in 1956, Horace formed his own group. It was a quintet, meaning five musicians: tenor saxophone, trumpet, piano, bass, and drums. They recorded many albums for Blue Note Records. This made Horace even more popular. His most successful album was Song for My Father, recorded in 1963 and 1964.

In the early 1970s, Horace made some changes. He stopped touring with his group to focus on composing. He also started adding lyrics to his songs. He became very interested in spiritual ideas. These new songs, like The United States of Mind series, were not very popular. After 28 years, Horace left Blue Note Records. He started his own record label called Silveto. He toured less in the 1980s, earning money from his popular songs.

In 1993, he returned to major record labels. He released five more albums. Later, health problems caused him to stop performing in public. As a pianist, Horace Silver moved from bebop to hard bop. He focused on clear melodies instead of complex harmonies. His right hand played clean, often funny lines. His left hand played darker notes and chords with a steady, rumbling sound.

His songs also had catchy melodies. Many of his well-known tunes became jazz standards. These include "Doodlin'", "Peace", and "Sister Sadie". They are still played widely today. Horace Silver had a huge impact on jazz. He influenced other pianists and composers. He also helped many young jazz musicians who played in his bands over four decades.

Contents

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Horace Silver was born on September 2, 1928, in Norwalk, Connecticut. His mother, Gertrude, was from Connecticut. His father, John Tavares Silver, was from the island of Maio, Cape Verde. He moved to the United States when he was young. Horace's mother was a maid and sang in a church choir. His father worked for a tire company.

Horace started playing the piano when he was a child. He also took classical music lessons. His father taught him the folk music of Cape Verde. When Horace was 11, he decided he wanted to be a musician. This happened after he heard the Jimmie Lunceford orchestra.

His early piano influences included boogie-woogie and the blues. He also admired pianists like Nat King Cole, Thelonious Monk, and Bud Powell. He even learned from some jazz horn players. Horace finished St. Mary's Grammar School in 1943. In high school, he played tenor saxophone in the band and orchestra. He played local gigs on both piano and saxophone while still in school. Around 1946, he moved to Hartford, Connecticut. There, he got a regular job as a pianist in a nightclub.

Career Highlights and Success

The 1950s: A Rising Star

Horace Silver's big break came in 1950. His trio was playing with saxophonist Stan Getz at a club in Hartford. Getz liked Horace's band so much that he hired them for his tour. Getz also gave Horace his first chance to record music in December 1950. After about a year, Horace left Getz's band and moved to New York City.

In New York, he quickly became famous. People loved his original songs and his bluesy piano style. He played for short times with famous saxophonists Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins. Then he met alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson. Horace learned a lot about bebop jazz from him.

Horace made his first recording for Blue Note Records in 1952. He was the pianist for Lou Donaldson. Later that year, Blue Note offered Horace his own recording session. He recorded mostly his own songs. He stayed with Blue Note as a bandleader for the next 28 years.

Horace also played as a sideman (a musician who plays with a main artist). In 1953 and 1954, he played on albums by Sonny Stitt, Miles Davis, and others. In 1954, Down Beat magazine named him the "new star" piano player. He also played at the first Newport Jazz Festival.

The Jazz Messengers and His Own Quintet

In New York, Horace Silver and Art Blakey started the Jazz Messengers. This group was run by both of them. Their first two studio recordings were made in late 1954 and early 1955. They were released as Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers. This album included Horace's first hit song, "The Preacher".

These recordings helped define a new style of jazz called hard bop. This style mixed elements of blues, gospel, and R&B with bebop. Hard bop became very popular and helped Blue Note Records become a successful company.

Horace left the Jazz Messengers in May 1956. Soon after, he formed his own quintet. Club owners wanted to hire him because of his popular albums. The first members of his quintet included Hank Mobley on tenor saxophone and Art Farmer on trumpet.

The quintet, with different musicians over time, continued to record. This helped Horace become even more famous. He wrote almost all the music his band played. One of his songs, "Señor Blues", became very well-known. When performing, Horace was very energetic. He would crouch over the piano, sweating, with his hair brushing the keys, and his feet tapping.

After 1957, Horace focused mostly on his own band. For several years, his quintet included Junior Cook on tenor saxophone and Blue Mitchell on trumpet. Their first album was Finger Poppin' in 1959. In 1962, Horace toured Japan, which inspired his album The Tokyo Blues. By the early 1960s, Horace's quintet was very popular in jazz clubs. They also released singles like "Blowin' the Blues Away" and "Sister Sadie" for jukeboxes and radio.

The 1960s: Song for My Father and Beyond

In early 1964, Horace visited Brazil. This trip made him more interested in his family's heritage. That same year, he formed a new quintet. It featured Joe Henderson on tenor saxophone and Carmell Jones on trumpet. This band recorded most of Horace's most famous album, Song for My Father. This album was very successful, reaching No. 95 on the Billboard 200 chart in 1965. It was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.

Horace continued to record and change band members. Sometimes his band even expanded to six musicians. In 1966, his album The Cape Verdean Blues also charted. The album Serenade to a Soul Sister (1968) included lyrics, showing Horace's new interest in writing words for his music. His quintet, including saxophonist Bennie Maupin, toured parts of Europe in late 1968. They also recorded You Gotta Take a Little Love, one of his last quintet albums for Blue Note.

Later Career and Legacy

The 1970s and 1980s: New Directions

At the end of 1970, Horace stopped his regular band. He wanted to focus on composing and spend more time with his wife, Barbara Jean Dove. They had a son named Gregory. From the early 1970s, Horace also became very interested in spiritual ideas.

He started including lyrics in more of his songs. The first album with vocals was That Healin' Feelin' (1970). This album was not very popular. Blue Note Records agreed to release two more albums with vocals. These three albums were later put together as The United States of Mind.

Horace formed a new touring band in 1973. It included brothers Michael and Randy Brecker. Around 1974, Horace and his family moved to California. This was after their New York City apartment was robbed. Horace and Barbara divorced in the mid-1970s.

In 1975, he recorded Silver 'n Brass. This was the first of five "Silver 'n" albums. These albums added other instruments to his quintet. His band members continued to change, often featuring talented young musicians. One of these was trumpeter Tom Harrell.

Horace's last Blue Note album was Silver 'n Strings, recorded in 1978 and 1979. He had been with Blue Note for the longest time in the label's history. Horace said he left Blue Note because the new owners were not interested in promoting jazz. In 1980, he started his own record label, Silveto. He said it was "dedicated to the spiritual, holistic, self-help elements in music."

The 1980s and 1990s: Independent and Return to Labels

The first Silveto album was Guides to Growing Up in 1981. It featured readings from actor Bill Cosby. Horace said he toured less, only four months a year, to spend more time with his son. This meant he had to find new band members every year. He continued to write lyrics for his new albums. The song titles showed his spiritual and self-help ideas. For example, Spiritualizing the Senses (1983) included "Seeing with Perception" and "Moving Forward with Confidence".

His next albums were There's No Need to Struggle (1983) and The Continuity of Spirit (1985). By the early 1990s, Horace did not play at jazz festivals often. But he still received money from his popular songs.

In 1991, a musical work called Rockin' with Rachmaninoff was performed in Los Angeles. Horace wrote the music for it. After trying to make his independent label work for ten years, Horace stopped it in 1993. He then signed with Columbia Records. This meant he mostly released instrumental music again. His first album with Columbia, It's Got to Be Funky, was a rare big band album.

Horace became very sick soon after this album was released. He had a blood clot problem. But he recovered and recorded Pencil Packin' Papa in 1994. That year, he also played as a guest on Dee Dee Bridgewater's album Love and Peace: A Tribute to Horace Silver.

Horace Silver received a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters award in 1995. The next year, he was added to Down Beat magazine's Jazz Hall of Fame. He also received an honorary music degree from Berklee College of Music. He moved from Columbia to Impulse! Records. There, he made the album The Hardbop Grandpop (1996) and A Prescription for the Blues (1997). The Hardbop Grandpop was nominated for two Grammy Awards.

He was unwell again in 1997, so he could not tour to promote his records. His last studio recording was Jazz Has a Sense of Humor in 1998 for Verve Records. Throughout his career, Horace always recorded his own new songs for his albums.

Later Years and Passing

Horace Silver performed in public for the first time in four years in 2004. He played with an octet (eight musicians) at the Blue Note Jazz Club in New York. After this, he was not seen in public very often. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences gave him its President's Merit Award. In 2006, his autobiography, Let's Get to the Nitty Gritty: The Autobiography of Horace Silver, was published. An album from a 1958 concert, Live at Newport '58, was released in 2008. It reached the top ten on Billboard's jazz chart.

In 2007, it was announced that Horace Silver had Alzheimer's disease. He passed away from natural causes in New Rochelle, New York, on June 18, 2014, at the age of 85. His son survived him.

Horace Silver's Playing Style

Horace Silver's early recordings showed a "crisp, cheerful but slightly unusual style." It was unique enough to stand out from the more complex bebop jazz. Unlike other bebop pianists, he focused on simple, clear melodies. He also used short musical phrases that appeared and disappeared during his solos.

His right hand played clean lines. His left hand added bouncy, darker notes and chords in a steady, rumbling way. Horace always played with a strong, clear sound, like he was hitting the keys. His way of using his fingers was special. This made his piano playing unique, especially the blues parts.

The Penguin Guide to Jazz said that his style used "blues and gospel-tinged elements." It also had a "percussive attack" and a "generous good humor." This gave all his records an upbeat feeling. Horace often quoted parts of other songs in his own playing, which added to the humor.

Writer Thomas Owens noted that Horace's solos had short, simple phrases. He also used a "blue fifth" (a quick slide to a flattened note). He often used low, rhythmic chords. He also used blues and minor pentatonic scales. Music journalist Marc Myers said that Horace could make music sound exciting and uplifting. He did this by moving from dark, minor parts to bright, major chords.

When he played along with a saxophonist or trumpeter, Horace was also unique. He didn't just react to the soloist's melody. Instead, he played background patterns. These were like the musical phrases that saxophones or brass instruments play behind soloists in big bands.

Horace Silver's Compositions

Early in his career, Horace wrote new melodies over existing song structures. He also wrote many blues-based songs. These included "Doodlin'" and "Opus de Funk". "Opus de Funk" was a typical Horace Silver song. It had advanced musical structure but also a catchy tune and a strong beat. He was one of the first to mix gospel and blues sounds into jazz. This happened at the same time these sounds were appearing in rock 'n' roll and R&B.

Horace soon expanded his writing style. He wrote "funky groove tunes, gentle mood pieces, and Latin songs." He also wrote fast jam numbers and almost every other kind of hard bop song. An unusual song is "Peace". This ballad focuses on creating a calm mood rather than complex melodies. Owens noted that many of his songs did not use folk blues or gospel. Instead, they had very colorful melodies with rich, unusual harmonies. His songs and arrangements also made his quintet sound like a much larger band.

Horace himself said that he found inspiration everywhere. "I'm inspired by nature and by some of the people I meet," he said. "I'm inspired by my mentors. I'm inspired by various religious doctrines." He also said that many of his songs came to him just before he woke up. Others came from simply playing around on the piano. He would jump out of bed to record a melody before he forgot it. Then he would work on adding harmonies and a middle section to the tune.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Horace Silver was one of the most influential jazz musicians of his time. Grove Music Online describes his legacy in at least four ways:

- He helped create hard bop jazz.

- He used the classic quintet setup (tenor saxophone, trumpet, piano, bass, and drums).

- He helped develop many young musicians who became important players and bandleaders.

- He was a very skilled composer and arranger.

Horace also influenced other pianists. His first Blue Note recording as a leader "changed jazz piano," according to Marc Myers. Before him, most jazz piano was based on the fast and strong playing of Bud Powell. As early as 1956, Down Beat magazine said Horace's piano playing influenced many modern jazz pianists. This included Ramsey Lewis, Les McCann, Bobby Timmons, and even Cecil Taylor.

Horace Silver's legacy as a composer might be even greater than as a pianist. His songs, many of which are jazz standards, are still played and recorded all over the world. As a composer, he brought back the focus on melody. Critic John S. Wilson noted that jazz musicians had written very complex songs for a long time. But "Silver wrote originals that were not only actually original but memorably melodic." This helped bring back melodic creativity among jazz writers.

Discography

Images for kids

-

Silver by Dmitri Savitski, 1989

-

Silver in Berkeley, California, 1983

-

At the North Sea Jazz Festival in The Hague, 1985

See also

In Spanish: Horace Silver para niños

In Spanish: Horace Silver para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |