Australian House of Representatives facts for kids

Quick facts for kids House of Representatives |

|

|---|---|

| 48th Parliament of Australia | |

Commonwealth Coat of Arms

|

|

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

|

Milton Dick, Labor

Since 26 July 2022 |

|

|

Leader of the House

|

Tony Burke, Labor

Since 1 June 2022 |

|

Manager of Opposition Business

|

Alex Hawke, Liberal

Since 28 May 2025 |

| Structure | |

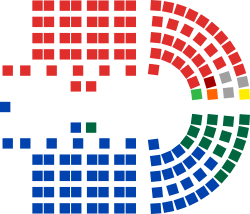

| Seats | 150 |

|

|

|

Political groups

|

Government (77) Labor (77) |

|

Length of term

|

3 years |

| Elections | |

| Full preferential voting | |

|

Last election

|

3 May 2025 |

|

Next election

|

By 20 May 2028 |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| House of Representatives Chamber Parliament House Canberra, Australian Capital Territory Australia |

|

The House of Representatives is like one of the two main teams in Australia's Parliament. It's often called the "lower house," and the other team is the Senate, or "upper house." Together, they make up Australia's law-making body. The rules for how the House of Representatives works are written in the Australian Constitution.

Members of the House of Representatives are usually elected for up to three years. However, elections often happen sooner than that. Since the 1970s, elections for both the House and the Senate have usually taken place at the same time.

People elected to the House of Representatives are called "Members of Parliament" (or "MPs"). Those in the Senate are called "Senators." In Australia's system of government, the political party that can show it has the support of most MPs in the House of Representatives forms the government. The leader of this party becomes the Prime Minister.

Currently, there are 150 members in the House of Representatives. Each member represents a specific area, called an "electoral division" or "electorate." The number of members can change a little over time as the population grows or shifts, leading to new boundaries for these electorates. For example, there were 151 members for the 2022 Australian federal election, but 150 seats were contested in the 2025 election.

When people vote for their MP, they use a system called "full preferential voting." This means voters rank all the candidates in order of their preference, from their favorite to their least favorite. This system helps make sure the winning candidate has the support of more than half the voters in their area.

Contents

Understanding Australia's House of Representatives

The Constitution of Australia created the House of Representatives in 1900 when Australia became a united country. The House is led by the Speaker. Members are elected from specific geographic areas called "electorates."

To make sure everyone's vote counts fairly, laws require that electorates within each state have roughly the same number of voters. In 2022, each seat had about 117,000 voters on average. However, smaller states are guaranteed at least five seats in the Constitution, even if their population is smaller. This means states like Tasmania might have more seats than their population alone would suggest. Electorate boundaries are redrawn regularly to keep voter numbers balanced.

The Constitution also says that the total number of seats in the House of Representatives should be almost double the number of Senators. This rule, called the "nexus provision," helps keep a balance of power between the two houses of Parliament. It ensures that the Senate, which represents the states equally, maintains its importance compared to the House, which represents people based on population.

The House of Representatives and the Senate have similar powers when it comes to making laws. Both houses must agree for a law to pass. However, laws about money (like taxes or spending) must start in the House of Representatives. This means the party with the most members in the House usually forms the government.

The Governor-General invites the leader of the party (or group of parties) with the most support in the House to become the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister then chooses other elected members from both the House and the Senate to become ministers. These ministers are in charge of different government departments.

The main job of the opposition party in the House is to question the government's plans and laws. They try to hold the government accountable by asking questions during "question time" and during debates.

Because of Australia's voting system, one party or group of parties almost always has a clear majority in the House. This makes it easier for the government to pass its laws there. In the Senate, however, it's more common for no single party to have a majority, so votes there are often more closely watched.

The House of Representatives chamber has green furnishings, similar to the British Parliament. In the new Parliament House (opened in 1988), the green was made lighter, like the leaves of a eucalyptus tree. The seating is shaped like a horseshoe, which is a mix of the traditional opposing benches and the curved seating found in many other countries' parliaments.

Australian parliamentary debates can sometimes be quite lively, with members often speaking passionately. The Speaker's job is to keep order and make sure everyone follows the rules.

How Members are Chosen: Australia's Voting System

Since the 1919 election, Australia has used "full preferential voting" to elect members of the House of Representatives. This system was introduced to ensure that the winning candidate has the support of more than half of the voters in their electorate.

Here's how full preferential voting works for the House of Representatives:

- Voters must write the number "1" next to their favorite candidate. This is called their "first preference."

- Then, voters must number all the other candidates on the ballot paper with "2," "3," and so on, in order of their preference. If a voter doesn't number every candidate, their vote might be considered "informal" (spoiled) and won't count.

- First, all the "1" votes are counted. If a candidate gets more than half of these first preference votes, they win!

- If no candidate gets more than half of the "1" votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is removed from the count.

- The votes for the removed candidate are then given to the voter's next preferred candidate (their "2" vote).

- This process continues, removing the candidate with the fewest votes and re-allocating their preferences, until one candidate has more than half of the votes.

After all the preferences are counted, it's possible to see how votes were shared between the two main political groups, usually the Coalition parties and the Australian Labor Party. This is called the "two-party-preferred" vote.

The House and the Government: How Decisions are Made

The Governor-General officially appoints and removes the "Ministers of State" who run government departments. In practice, the Governor-General follows a tradition where the government is formed by the party or group of parties that has the most members in the House of Representatives. The leader of this group becomes the Prime Minister.

A smaller group of the most important ministers forms the Cabinet. Cabinet meetings are private and are where big decisions and policies are discussed. While the Constitution doesn't officially recognize the Cabinet, its decisions are very important. They are later formally approved by the Federal Executive Council, which is Australia's highest official executive body.

A minister must be a member of either the House of Representatives or the Senate when they are appointed, or become one within three months. This rule ensures that ministers are accountable to the Parliament.

Teamwork in Parliament: Understanding Committees

Besides the main debates in the chamber, the House of Representatives also has many committees. These committees look into specific topics or proposed laws that the main House sends to them. They allow all MPs to ask questions of ministers and government officials. They also conduct investigations, study policies, and examine new laws.

Once a committee finishes its work, its members write a report. This report is then presented to Parliament and includes what they found and any suggestions they have for the government.

Parliamentary committees have important powers. One key power is being able to ask people to come to hearings to share information and documents. If someone tries to stop a committee's work, or refuses to answer questions or provide documents, they could be found in "contempt of Parliament." This means they have disrespected the Parliament.

Everything said in committee meetings is recorded and protected by "parliamentary privilege." This means that committee members and witnesses are safe from legal action for anything they say during a hearing. Written information given to a committee is also protected.

There are different types of committees:

- Standing committees are permanent. They check new laws, government budgets, and how departments are performing.

- Select committees are temporary. They are set up to investigate specific issues.

- Domestic committees manage the House's own affairs, like how it handles new laws or issues of parliamentary privilege.

- Legislative scrutiny committees examine laws and rules to see how they affect people's rights.

- Joint committees include members from both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Federation Chamber: A Second Place for Debates

The Federation Chamber is like a second debating room for the House of Representatives. It handles topics that are usually less controversial. However, it can't start new laws or make final decisions on them. It helps the main House by discussing things at the same time.

The Federation Chamber was created in 1994 (originally called the Main Committee) to help the House manage its workload. It's designed to be less formal, needing only three members to be present: the Deputy Speaker, one government member, and one non-government member. For a decision to be made in the Federation Chamber, everyone must agree. If there's any disagreement, the issue goes back to the main House for a vote.

Because it's a part of the House, the Federation Chamber can only meet when the main House is also meeting. If there's a vote in the main House, members in the Federation Chamber must go back to the main chamber to cast their vote. The Federation Chamber is located in one of the Parliament House committee rooms, set up to look like a smaller version of the main House chamber.

Election Results Explained

See also

In Spanish: Cámara de Representantes de Australia para niños

In Spanish: Cámara de Representantes de Australia para niños

- Australian House of Representatives committees

- Canberra Press Gallery

- Chronology of Australian federal parliaments

- Clerk of the Australian House of Representatives

- List of Australian federal by-elections

- List of longest-serving members of the Parliament of Australia

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Australian Parliament who represented more than one state or territory

- Speaker of the Australian House of Representatives

- Women in the Australian House of Representatives

- Browne–Fitzpatrick privilege case, 1955