Housecarl facts for kids

A housecarl (called húskarl in Old Norse) was a special kind of soldier or bodyguard in medieval Northern Europe. They were not slaves but free men who worked for a lord or king.

This idea started with the Norsemen in Scandinavia. It came to Anglo-Saxon England in the 11th century when the Danes conquered the area. Housecarls were highly trained and paid full-time soldiers. In England, the king's housecarls did many jobs, both fighting and helping to run the country. They famously fought alongside King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings.

Contents

What Does "Housecarl" Mean?

The word "housecarl" comes from the Old Norse term húskarl. This literally means "house man." The word karl is similar to the Old English word churl, which meant a free man or peasant.

Sometimes, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle used the word hiredmenn for all paid warriors, including housecarls. It also mentioned butsecarls and lithsmen. It is not fully clear if these were types of housecarls or different groups of fighters.

Free Workers and Bodyguards

At first, the Old Norse word húskarl simply meant "manservant." This was different from the húsbóndi, who was the "master of the house." Housecarls were free men, not slaves. They chose to work for someone else.

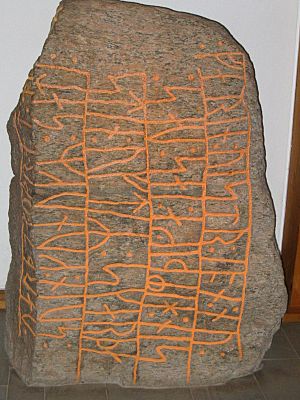

Over time, "housecarls" began to mean "retainers" or "bodyguards." These were men who served a lord or king in his special group of fighters. This meaning can be seen on old stones like the Turinge stone. It talks about housecarls remembering their leader who fought in battle. This shows that housecarls were soldiers who served someone important.

King's Men in Norway

In Norway, housecarls were part of the king's special group called the hirð. This group had been around since the 800s. Old texts like the Heimskringla and the Konungs skuggsjá (King's Mirror) show the strong link between a king and his housecarls.

If someone killed a king's man, there was a special fine. This was one benefit of joining the king's service. In return, housecarls were expected to get revenge if their leader was killed.

A poet named Sigvatr Þórðarson called the housecarls of King Olaf II of Norway heiðþegar. This means "gift-receivers" or "pay-receivers." This suggests they were free men who served a king and received gifts or payment for their service. We know that in the 1060s, royal housecarls were paid with Norwegian coins.

Danish Kings' Housecarls: The Heimþegar

Several runestones in Denmark use the term heimþegi. This means "home-receiver," suggesting someone who was given a house by another. These heimþegar were very similar to housecarls. They served a king or lord and received gifts, like homes, for their service. Some historians believe heimþegi was just a local Danish word for húskarl.

Historians think that the soldiers at the Danish fort of Trelleborg might have been royal housecarls. Kings Svein Forkbeard and Cnut the Great might have used these royal housecarls to protect the country.

One of the Hedeby stones, the Stone of Eric (DR 1), was put up by a royal retainer for his friend. It says:

Thurlf, Sven's retainer [heimþegi], put up this stone for Erik his friend, who died when the warriors were around [besieging Hedeby]. He was a commander, a very brave warrior.

"Sven" here was likely King Svein Forkbeard. Another stone, the Skarthi stone (DR 3), was put up by King Svein himself for his retainer, Skarði.

When Danish kings like Svein Forkbeard and Cnut the Great ruled England, they created a group of royal housecarls there. These housecarls had rules that mixed Norse traditions with church laws. Even after the Danish kings lost England, housecarls continued in Denmark. However, by the late 1100s, housecarls in Denmark likely changed into a new type of noble class. These nobles no longer lived at the king's court.

Housecarls in England

The term "housecarl" came to England when Svein Forkbeard and Cnut the Great conquered it. Cnut's housecarls were very disciplined bodyguards. It is not clear if all of Cnut's housecarls were from Scandinavia. Some historians believe many of them were English.

Housecarls were just one type of paid soldier in England before the Norman Conquest. Other paid groups included lithsmen and butsecarls, who were skilled in both land and sea fighting. Sometimes, foreign warriors also served important English lords. For example, some old records call Earl Tostig's men hiredmenn, while others call them hus karlas. This suggests "housecarl" could also mean a mercenary or retainer, not just a royal bodyguard. It also helped tell them apart from the unpaid local army called the fyrd.

How Royal Bodyguards Were Organized

According to a Danish historian from the 1100s, Svend Aggesen, Cnut's housecarls followed a special set of rules called the Witherlogh. This group or guild was organized in a Scandinavian way. However, the legal rules in the Witherlogh came mostly from church law or Anglo-Saxon laws.

The Witherlogh set out how housecarls should behave. For example, they sat at the king's table based on their fighting skill and noble background. If they did something wrong, like not taking good care of another housecarl's horse, they could be moved to a lower seat. After three such mistakes, they would sit at the very lowest place. No one was allowed to talk to them, but others could throw bones at them.

Killing another housecarl meant being declared an outlaw and sent away. Treason was punished by death and losing all property. Arguments between housecarls were settled by a special court called the Huskarlesteffne, with the king present. However, we only know about the Witherlogh from Svend Aggesen's writing, which was more than 100 years after Cnut's time. So, we cannot be completely sure how accurate it is.

Pay, Land, and Social Role

A special tax was collected to pay the royal housecarls in coins. One historian, Saxo Grammaticus, said they were paid every month. Because they received wages, some people see housecarls as a type of mercenary. Other old texts call them "men receiving wages" or "paid men."

Housecarls were not forced to serve forever. There was only one day a year, New Year's Eve, when they could leave the king's service. On this day, Scandinavian kings usually gave gifts to their retainers.

Not many housecarls received land from the king. By 1066, the Domesday Book shows only 33 housecarls who owned land, and these lands were small. So, it seems that English landowners did not lose their property to give land to the king's housecarls. However, some of Cnut's housecarls were quite wealthy. For example, the Abbotsbury Abbey was founded by one of them or his wife.

Administrative Duties

In times of peace, royal housecarls also had some administrative jobs. They acted as the King's representatives. For example, in 1041, there was a revolt in Worcester against a very high tax. Two of King Harthacnut's housecarls, who were collecting taxes, were killed during this revolt.

Military Role and Importance

There are different ideas about what Cnut's housecarls were exactly. Some sources say Cnut kept 3,000 to 4,000 men in England as his bodyguards. One idea is that these men were his housecarls, forming a well-trained, professional standing army for the king. However, another idea is that there was no large, standing royal army in England in the 11th century.

This debate affects how we see housecarls. Were they an elite fighting group? Some historians, like Charles Oman, believed that housecarls at Hastings had strong team spirit. This idea comes from Svend Aggesen's description of Cnut's housecarls following a strict code.

More recently, historian Nicholas Hooper has questioned this. He thinks housecarls were not very different from Saxon thegns. He believes they were mainly retainers who received land or pay, but not necessarily a standing army. Hooper suggests that while housecarls might have had better training and equipment than the average soldier, they were not always a clearly defined military elite.

Another idea is that the royal housecarls were a smaller group of household troops, partly based at the king's court. During the time of Edward the Confessor, a group of sailors and soldiers called lithsmen were paid wages and possibly based in London. Some believe these lithsmen were the main standing army, with housecarls as a smaller, secondary force.

One reason to doubt the existence of a large standing army of housecarls is that when a revolt happened in 1051, no such army was used to quickly stop it.

Harold Godwinson's Housecarls: Stamford Bridge and Hastings

By the late 11th century in England, there might have been as many as 3,000 royal housecarls. As King Harold Godwinson's personal troops, housecarls were vital to his army at Hastings. Even though they were a smaller part of Harold's army, their better equipment and training meant they could strengthen the local militia, or fyrd.

The housecarls were placed in the center of the army, around Harold's standard. They were also likely in the front lines of both sides, with the fyrdmen behind them. In the Battle of Hastings, these housecarls fought bravely even after Harold died. They kept their promise to him until the very last man was killed.

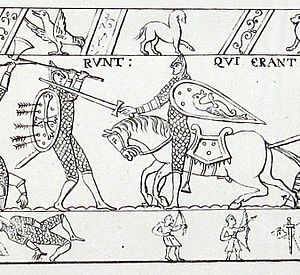

The Bayeux Tapestry shows housecarls as foot soldiers wearing mail armor and conical nasal helmets. They are shown fighting with large, two-handed long axes.

See also

- Comitatus

- Druzhina

- Hird

- Leidang

- Yeomen of the Guard

- Thingmen

Images for kids

-

Runestone U 330, one of the Snottsta and Vreta Runestones in Uppland, Sweden. It mentions Assurr/Ôzurr, the housecarl of the owner of the Snottsta estate.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |