History of Anglo-Saxon England facts for kids

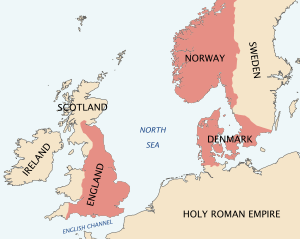

Anglo-Saxon England, also known as Early Medieval England, was a period in history from the 5th to the 11th centuries. It began after the end of Roman rule in Britain and lasted until the Norman conquest in 1066. During this time, different Anglo-Saxon kingdoms existed until they were united into the Kingdom of England in 927 by King Æthelstan. Later, in the 11th century, England became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire under Cnut the Great, which also included Denmark and Norway.

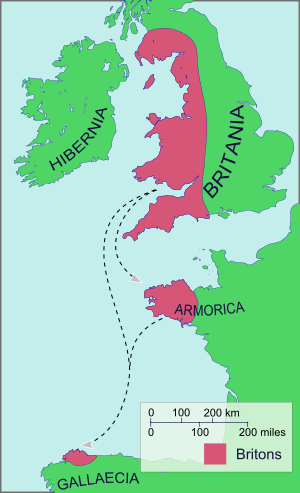

The Anglo-Saxons were groups of people who spoke Germanic languages. They moved to the southern part of Great Britain from nearby northwestern Europe. Their history starts after the Romans left Britain. It covers the time when Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were formed in the 5th and 6th centuries. These included seven main kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex.

The Anglo-Saxons became Christian in the 7th century. Later, they faced attacks from Vikings and saw Danish settlers arrive. England gradually became united under the rule of Wessex in the 9th and 10th centuries. This period ended with the Norman conquest by William the Conqueror in 1066.

Even after the Norman conquest, Anglo-Saxon identity continued. It became known as Englishry under Norman rule. Over time, Anglo-Saxons mixed with Celts, Danes, and Normans, forming the modern English people.

Contents

How Anglo-Saxon England Began

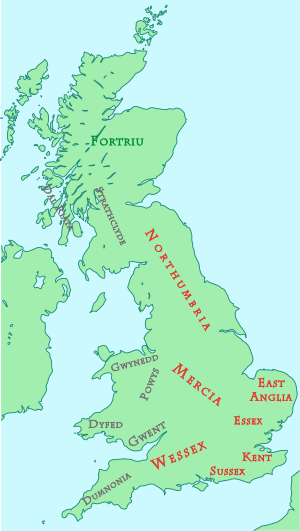

As the Roman Empire's control over Britain ended, the Roman army left. This left the Romano-British leaders with a big problem: attacks from raiders, especially the Picts on the east coast. To protect themselves, the Romano-British leaders hired Anglo-Saxon fighters, called foederati. They gave them land in return for their help.

Around 442, the Anglo-Saxons rebelled, possibly because they weren't paid. The Romano-British asked the Roman commander for help, but the Roman Emperor had already told them to defend themselves. This led to many years of fighting between the British and the Anglo-Saxons. The fighting slowed down around 500, when the British won a big victory at the Battle of Mount Badon.

Early Germanic Arrivals in Britain

Germanic people had been coming to Britain even before the Roman Empire fell. Some of the first were soldiers from the Batavian tribe, who were part of the Roman invasion force in AD 43. The Romans often added fighters from Germanic lands to their armies, including those in Britain. Graves of these soldiers and their families have been found in Roman cemeteries.

More Anglo-Saxons arrived after the Roman army left, hired to defend Britain. They also came during the Anglo-Saxon rebellion in 442. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were founded when small groups of invaders arrived by ship, fought the British, and took over their lands. However, historians still debate exactly what happened between the Roman departure and the Norman arrival.

British and Anglo-Saxon Co-existence

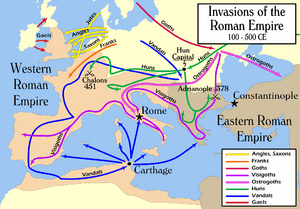

The arrival of Anglo-Saxons in Britain was part of a larger movement of Germanic peoples across Europe between 300 and 700 AD. This time is known as the Migration period. During this period, many Britons also moved to areas like Brittany and Normandy in modern-day France, and even to Galicia in Spain.

One traditional view was that Anglo-Saxons came in large numbers, fighting and pushing the British people to the western parts of the islands or across the sea. This idea came from writers like Bede, who wrote about the British being killed or enslaved. However, a more modern view suggests that the British and Anglo-Saxons lived side by side. For example, the Laws of Ine show that British people could be wealthy freemen, though they generally had a lower social status than Anglo-Saxons. Historians still discuss how many Anglo-Saxons migrated and whether they were a small group of leaders or a large number of people.

Early British resistance was led by a man named Ambrosius Aurelianus. The British won a "final" victory at the Battle of Mount Badon around 500 AD. This battle might have temporarily stopped the Anglo-Saxon movement. After this, there was a time of peace and wealth. But even so, the Anglo-Saxons took control of Sussex, Kent, East Anglia, and parts of Yorkshire. The West Saxons also started a kingdom in Hampshire around 520.

It took about 50 years for the Anglo-Saxons to make major advances again. During this time, the British were weakened by civil wars and unrest. The next big campaign against the British was in 577, led by Ceawlin, king of Wessex. His forces captured Cirencester, Gloucester, and Bath. But this expansion ended when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting among themselves. Ceawlin was replaced and later killed.

Kingdoms and Christianity (7th and 8th Centuries)

By 600 AD, new kingdoms and smaller territories were forming. A medieval historian, Henry of Huntingdon, came up with the idea of the Heptarchy. This term means "seven rules" and refers to the seven main Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Main Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

The four most powerful kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England were:

- East Anglia

- Mercia

- Northumbria, which included smaller areas called Bernicia and Deira

- Wessex

There were also other smaller kingdoms and territories.

At the end of the 6th century, Æthelberht of Kent was the most powerful ruler. His lands reached north to the Humber River. In the early 7th century, Kent and East Anglia were the leading kingdoms. After Æthelberht died in 616, Rædwald of East Anglia became the most powerful leader south of the Humber.

After Rædwald's death, Edwin of Northumbria expanded Northumbrian power. However, the Mercians, led by Penda, teamed up with the Welsh King Cadwallon ap Cadfan. They invaded Edwin's lands, defeating and killing him in 633. Their success was short-lived, as Oswald of Northumbria defeated and killed Cadwallon. But Penda fought Northumbria again and killed Oswald in 642.

Oswald's brother, Oswiu, eventually killed Penda. Mercia then spent the rest of the 7th and 8th centuries fighting the kingdom of Powys. This war reached its peak during the reign of Offa, who built a 150-mile-long dyke that formed the border with Wales. The power of Mercia ended in 825 when they were defeated by Egbert of Wessex.

Becoming Christian

Christianity had been present in Britain during Roman times. The Roman Emperor Constantine allowed Christianity in 313, and later it became the official religion of the Roman Empire. It's not clear how many Britons were Christian when the pagan Anglo-Saxons arrived.

Saint Patrick is famous for converting the Irish. A Christian Ireland then helped spread Christianity to the rest of the British Isles. Columba founded a religious community in Iona, Scotland. Then Aidan was sent from Iona to set up a church in Northumbria, at Lindisfarne, between 635–651. So, Northumbria became Christian through the Irish church.

Pope Gregory I sent Augustine in 597 to convert the Anglo-Saxons in the south. King Æthelberht of Kent gave Augustine land to build a church in Canterbury. Augustine baptized Æthelberht in 601 and continued his mission. Most of northern and eastern England had already been reached by the Irish Church. However, Sussex and the Isle of Wight remained mostly pagan until Saint Wilfrid converted them around 681–683.

It's hard to know exactly what "conversion" meant back then. Church writers often said a place was "converted" just because the local king was baptized, even if he didn't fully follow Christian practices or if his people didn't. When churches were built, they sometimes included both pagan and Christian symbols to appeal to the Anglo-Saxons.

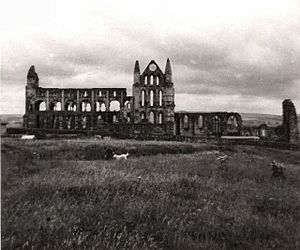

Even after Christianity was established, there were disagreements between those who followed Roman Christian practices and those who followed Irish practices. These arguments were about things like the date of Easter and how monks cut their hair. In 664, a meeting was held at Whitby Abbey, called the Whitby Synod, to decide these matters. Saint Wilfrid argued for the Roman ways, and Bishop Colmán for the Irish ways. Wilfrid's side won, and the Roman practices were adopted by the English church.

Viking Attacks and Wessex's Rise (9th Century)

Between the 8th and 11th centuries, raiders and settlers from Scandinavia, mainly Danes and Norwegians, attacked Western Europe, including Britain. These raiders were known as Vikings. The first raids in Britain happened in the late 8th century, mostly targeting churches and monasteries because they were rich. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that the holy island of Lindisfarne was attacked in 793. After a break, raids became more common around 835.

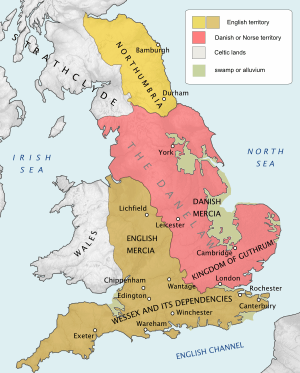

In the 860s, the Danes launched a full invasion instead of just raids. In 865, a large army arrived, which the Anglo-Saxons called the Great Heathen Army. Within ten years, almost all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell to the invaders: Northumbria in 867, East Anglia in 869, and most of Mercia by 877. Only the Kingdom of Wessex survived.

In March 878, the Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred, built a fortress in the marshes of Somerset. From there, he fought the Vikings. In May 878, he gathered an army and defeated the Viking army at the Battle of Edington. The Vikings retreated, and Alfred besieged them. Their leader, Guthrum, agreed to leave Wessex and be baptized. A peace treaty was signed, defining the areas ruled by the Danes (called the Danelaw) and by Wessex. Wessex controlled parts of the Midlands and the South, while the Danes held East Anglia and the North.

After his victory, Alfred changed Wessex into a kingdom ready for war. He built a navy, reorganized the army, and created a system of fortified towns called burhs. He often used old Roman cities for his burhs, rebuilding their defenses. To support these defenses and the army, he set up a tax system. These burhs protected Wessex from Viking attacks and also became important trading centers. A new wave of Danish invasions began in 891, lasting over three years. Alfred's defense system worked, and the Danes eventually gave up in 896.

Alfred is also remembered as a king who valued learning. He or his court started the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written in Old English, not Latin. Alfred himself translated many books.

England Becomes United (10th Century)

When Alfred died in 899, his son Edward the Elder became king. Alfred's son Edward and his grandsons Æthelstan, Edmund I, and Eadred continued to fight the Vikings. In Mercia, Æthelred ruled the western half and married Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd. When Æthelred died in 911, Æthelflæd, known as the "Lady of the Mercians," led the Mercian army. She worked with her brother, Edward the Elder, to take back Mercian lands from the Danes.

Edward and his successors expanded Alfred's network of fortified burhs, which helped them go on the attack. Edward recaptured Essex in 913. Edward's son, Æthelstan, took over Northumbria and made the Welsh kings submit to him. At the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, he defeated an alliance of Scots, Danes, and Vikings, becoming King of all England.

Some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, along with the British and settled Danes, did not like being ruled by Wessex. So, when a Wessex king died, there were often rebellions, especially in Northumbria. In 973, Alfred's great-grandson, Edgar, was crowned King of England and Emperor of Britain. His coins were marked "Edgar, King of the English." Edgar's coronation was a grand event, and many of its traditions were still used in the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953.

The Danish and Norse settlers in the Danelaw had a lasting impact. Even a hundred years later, they still saw themselves as "armies." More than 3,000 words in modern English have Scandinavian roots. Also, over 1,500 place-names in England are of Scandinavian origin. For example, names like Howe come from the Old Norse word haugr, meaning hill.

Danish Rule and Norman Conquest (978–1066)

Two years after his coronation, Edgar died young. He left two sons, Edward (the older) and Æthelred. Edward was crowned king, but three years later he was killed. So, Æthelred II became king in 978. He reigned for 38 years, but he earned the nickname "Æthelred the Unready" because he was not a strong ruler. A historian named William of Malmesbury, writing about 100 years later, criticized Æthelred, saying he just occupied the kingdom instead of governing it.

Around the time Æthelred became king, the Danish King Gormsson was trying to force Christianity on his people. Many of his subjects didn't like this, and his son, Sven, drove him out. These rebels, without a home, likely started the first new waves of raids on the English coast. The raids were so successful that Danish kings decided to join in.

In 991, the Vikings attacked Ipswich and landed near Maldon in Essex. The Danes demanded a ransom, but the English commander Byrhtnoth refused. He was killed in the Battle of Maldon, and the English were easily defeated. After this, the Vikings raided wherever they wanted, as the English offered little resistance. Even Alfred's system of burhs failed. Æthelred often hid from the raiders.

Paying the Danegeld

By the 980s, the kings of Wessex had strong control over the country's money. There were about 300 money-makers and 60 mints. Every few years, old coins were replaced with new ones. This system allowed the king to raise large amounts of money quickly. After the Battle of Maldon, Æthelred decided to pay the Danes a ransom, known as Danegeld, instead of fighting. A peace treaty was made to stop the raids. However, paying the Vikings only encouraged them to come back for more.

The Dukes of Normandy allowed Danish adventurers to use their ports for raids on England. This made relations between England and Normandy very tense. Eventually, Æthelred made a treaty with the Normans and married Emma, daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy, in 1002. This was an attempt to stop the link between the raiders and Normandy. Then, in November 1002, Æthelred ordered the killing of Danes living in England.

The Rise of Cnut

In 1013, Sven Forkbeard, King of Denmark, brought his fleet to England. He went north to the Danelaw, where the locals supported him. He then moved south, forcing Æthelred to flee to Normandy (1013–1014). However, Sven died suddenly in 1014. Æthelred returned to England and drove Sven's son, Cnut, back to Denmark.

In 1015, Cnut launched a new campaign against England. Edmund disagreed with his father, Æthelred, and fought on his own. Some English leaders supported Cnut, so Æthelred retreated to London. Æthelred died before fighting the Danish army, and Edmund became king. The Danish army surrounded London, but Edmund escaped and raised an army. Edmund's army defeated the Danes, but this success was short-lived. At the battle of Ashingdon, the Danes won, and many English leaders were killed. Cnut and Edmund agreed to split the kingdom: Edmund would rule Wessex, and Cnut the rest.

In 1017, Edmund died mysteriously, likely murdered by Cnut or his supporters. The English council confirmed Cnut as king of all England. Cnut divided England into earldoms, giving most to Danish nobles, but he made an Englishman, Godwin, earl of Wessex. Godwin later became part of the royal family. In 1017, Cnut married Æthelred's widow, Emma. Emma agreed to marry him if their children would be next in line for the English throne. Cnut already had two sons, Svein and Harold Harefoot, with another woman, but the church considered her his concubine, not his wife. Cnut and Emma had a son named Harthacnut.

When Cnut's brother, Harald II, King of Denmark, died in 1018, Cnut went to Denmark to secure his rule there. Two years later, Cnut also took control of Norway.

Edward Becomes King

Cnut's marriage to Emma caused problems with who would be king after his death in 1035. The throne was claimed by Ælfgifu's son, Harald Harefoot, and Emma's son, Harthacnut. Emma supported Harthacnut. Her son by Æthelred, Edward, tried to raid Southampton but failed, and his brother Alfred was murdered in 1036. Emma fled when Harald Harefoot became king of England.

When Harald Harefoot died in 1040, Harthacnut became king. He quickly became unpopular because he imposed high taxes. Edward was invited back from exile in Normandy to be Harthacnut's heir. When Harthacnut died suddenly in 1042, Edward (known as Edward the Confessor) became king.

Edward was supported by Earl Godwin of Wessex and married Godwin's daughter. This marriage was for convenience, as Godwin was thought to be involved in the murder of Edward's brother, Alfred. In 1051, Edward's relative, Eustace, arrived in Dover, and the people of Dover killed some of Eustace's men. When Godwin refused to punish them, the king, who was already unhappy with the Godwins, called them to trial. The Godwins fled rather than face trial. Norman stories say that Edward then offered the throne to his cousin, William, Duke of Normandy. However, Anglo-Saxon kings were chosen by a council, not by family inheritance, so this is unlikely.

The Godwins later threatened to invade England. Edward wanted to fight, but at a meeting, Earl Godwin surrendered and asked to clear his name. The king and Godwin made up, and the Godwins became the most powerful family in England after the king. When Godwin died in 1053, his son Harold became Earl of Wessex. Harold's brothers were given other earldoms. One brother, Tostig, was disliked in Northumbria for his harsh rule and was exiled. This caused a disagreement between Harold and Tostig.

Edward the Confessor's Death

On December 26, 1065, Edward became ill and fell into a coma. He woke briefly and asked Harold Godwinson to protect the Queen and the kingdom. Edward the Confessor died on January 5, 1066. Harold was declared king the next day and crowned on January 6, 1066.

Although Harold Godwinson took the crown, others claimed it. William, Duke of Normandy, Edward the Confessor's cousin, believed Edward had promised him the throne. The Normans also claimed that Harold had sworn a special oath of loyalty to William after being held prisoner in Normandy.

Harald Hardrada of Norway also claimed the English throne. His claim came through Cnut and his successors, and a pact between Harthacnut and Magnus, King of Norway.

Harold's estranged brother, Tostig, was the first to act. He traveled to Normandy to get help from William, but William wasn't ready. Tostig then sailed to Norway and successfully got help from Harald Hardrada. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says Tostig landed on the Isle of Wight in May 1066, raided the English coast, and then joined Hardrada.

Battles Before the Norman Conquest

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Tostig became Hardrada's helper. With about 300 longships, they sailed up the Humber estuary and landed at Riccall on September 24. They marched towards York and were met by English forces led by the northern earls, Edwin and Morcar, at Fulford Gate. The battle of Fulford on September 20 was very bloody. The English forces were defeated, but Edwin and Morcar escaped. The Vikings entered York, took hostages, and got supplies.

When Harold Godwinson heard the news in London, he quickly marched his army north. On September 25, he surprised Harald Hardrada and won a complete victory over the Vikings at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Harold allowed the survivors to leave in 20 ships.

William of Normandy Invades England

Harold was celebrating his victory at Stamford Bridge on September 26/27, 1066. Meanwhile, William of Normandy's invasion fleet set sail for England on the morning of September 27, 1066. Harold marched his army back to the south coast, where he met William's army at a place now called Battle, just outside Hastings. Harold was killed when he fought and lost the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066.

The Battle of Hastings almost completely destroyed the Godwin family. Harold and his brothers were killed on the battlefield. Tostig had been killed at Stamford Bridge. The Godwin women were either dead or childless.

William marched on London. The city leaders surrendered the kingdom to him, and he was crowned at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. It took William another ten years to fully control his new kingdom. He brutally crushed any opposition. In a very harsh process called the Harrying of the North, William ordered the destruction of the north, burning crops and poisoning the land. A chronicler said that over 100,000 people died of starvation. This was a huge number, about one in 20 people in England at the time.

By the time William died in 1087, most of England's Anglo-Saxon rulers were dead, exiled, or had become peasants. Only about 8 percent of the land was still under Anglo-Saxon control. Almost all Anglo-Saxon cathedrals and abbeys were torn down and rebuilt in the Norman style by 1200.

Images for kids

-

Escomb Church, a restored 7th-century Anglo-Saxon church. Church architecture and artefacts provide a useful source of historical information.

See also

In Spanish: Inglaterra anglosajona para niños

In Spanish: Inglaterra anglosajona para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |