Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic facts for kids

Hyperinflation is when prices for goods and services rise extremely fast. It happened to the German currency, the German Mark, between 1921 and 1923, especially in 1923. Germany's money had already lost a lot of value during World War I. This was because the German government paid for the war by borrowing money. By 1918, Germany owed 156 billion marks.

After the war, this huge debt grew even more. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 made Germany pay 50 billion marks in reparations. These payments were in cash and in goods like coal and timber.

The inflation got worse after the war. In August 1921, Germany's central bank started buying foreign money with German paper money at any price. They said this was to pay reparations. The German Mark became a little stable in early 1922. But then, hyperinflation exploded. By December 1922, one US dollar was worth 7,400 marks. This continued into 1923. By November 1923, one US dollar was worth an incredible 4,210,500,000,000 (over 4 trillion) German marks.

To fix this, Germany created a new currency called the Rentenmark. This money was backed by special bonds. Later, the Rentenmark was replaced by the Reichsmark. The government also stopped the national bank from printing more paper money.

By 1924, the currency was stable again. Germany also started paying reparations under the Dawes Plan. Because the value of the mark had dropped so much, many debts were wiped out. Some debts, like mortgages, were revalued. This meant lenders could get some of their money back.

Hyperinflation caused a lot of problems inside Germany. Experts still argue about what caused this hyperinflation. They especially debate how much the reparations payments were to blame.

Contents

Why It Happened

Money Problems During World War I

To pay for the huge costs of World War I, Germany stopped linking its money to gold in 1914. This is called the gold standard. Unlike France, which raised taxes to pay for the war, Germany decided to pay for the war by borrowing money.

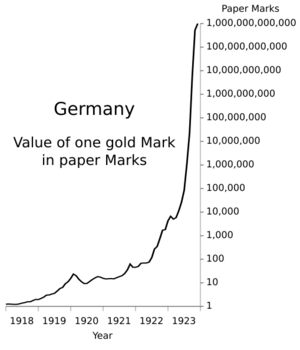

The government thought they would win the war. They planned to make the defeated Allies pay them back. They hoped to take over rich industrial areas and get cash payments from other countries. This was similar to what happened after Germany won against France in 1870. Because of this plan, the German mark slowly lost value against the US dollar. It went from 4.2 marks per dollar in 1914 to 7.9 marks per dollar by 1918. This was an early sign of the extreme inflation that came after the war.

Germany lost the war, so this plan failed. The new government, called the Weimar Republic, was left with huge war debts. They owed 156 billion marks in 1918. The problem got worse because they kept printing money without enough goods or resources to support it.

The famous economist John Maynard Keynes wrote about this in 1919. He said that governments printed money when they couldn't get enough from loans or taxes.

Inflation Right After World War I

The value of German money kept falling after World War I. By late 1919, Germany had signed the Treaty of Versailles. This treaty made Germany pay a lot of money to the Allied powers. They had to pay in cash and in goods like coal and timber. By then, 48 paper marks were needed to buy one US dollar.

In May 1921, the total amount Germany had to pay was set at 132 billion gold marks. This was part of the London Schedule of Payments. Germany had to make quarterly payments.

The German currency was fairly stable in the first half of 1921. One dollar was worth about 90 marks. Germany's factories and industries were mostly fine after the war. This put Germany in a better economic spot than France or Belgium.

Germany made its first payment of one billion gold marks in June 1921. Allied officials were in charge of customs in western Germany to make sure payments were made. After this first payment, most Allied officials left. Only small cash payments were made for the rest of 1921 and 1922.

From August 1921, the head of the Reichsbank, Rudolf Havenstein, started buying foreign money with marks at any price. This made the mark lose value even faster. German officials said this was to get foreign money for reparations. But British and French experts believed Germany was trying to ruin its own currency. They thought Germany wanted to avoid paying reparations and making budget changes. Records later showed that delaying currency and budget changes was seen as helpful. Even though hyperinflation was bad for the economy, it helped the German government. It greatly reduced the value of Germany's war debts, which were owed in paper marks.

In the first half of 1922, the mark stabilized at about 320 marks per dollar. Meetings were held to find a solution. One meeting in June 1922 was organized by US banker J. P. Morgan, Jr.. But no good solution was found. Inflation then turned into hyperinflation. By December 1922, the mark fell to 7,400 marks per US dollar. The cost of living went up 17 times in just six months.

In January 1923, France and Belgium sent troops to occupy the Ruhr valley. This was Germany's main industrial area. They did this because Germany failed to deliver coal reparations for the 34th time. About 900 million gold marks in reparations were collected this way.

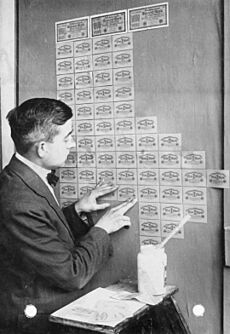

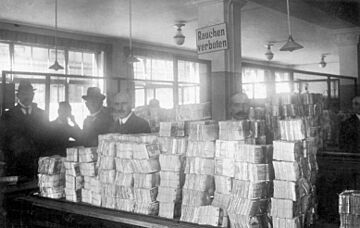

The German government told workers in the Ruhr to resist passively. This meant they should do nothing to help the French and Belgians. This was like a general strike. The government paid these striking workers by printing more and more banknotes. This flooded Germany with paper money, making hyperinflation even worse.

Hyperinflation in Action

Imagine a loaf of bread in Berlin. At the end of 1922, it cost about 160 Marks. By late 1923, that same loaf of bread cost 200,000,000,000 (200 billion) Marks!

By November 1923, one US dollar was worth an unbelievable 4,210,500,000,000 (over 4 trillion) German marks.

Fixing the Money

The hyperinflation crisis made economists and politicians look for a way to make German money stable again. In August 1923, an economist named Karl Helfferich suggested a new currency. He called it the "Roggenmark" (rye mark). It would be backed by bonds linked to the price of rye grain. But this plan was rejected because the price of rye changed too much.

Agriculture Minister Hans Luther then suggested a plan using gold instead of rye. This led to the creation of the Rentenmark (mortgage mark). It was backed by bonds linked to the market price of gold. These gold bonds were set at the same value as the pre-war gold marks. Rentenmarks could not be exchanged for actual gold. They were only linked to the gold bonds. This plan was approved in October 1923. A new bank, the Rentenbank, was set up by Hans Luther.

After November 12, 1923, when Hjalmar Schacht became the currency commissioner, Germany's central bank (the Reichsbank) was not allowed to print any more government money. This meant no more paper marks were printed. The Rentenmarks were allowed to be used for business, but their printing was carefully controlled. The Rentenbank did not lend money to the government or to people trying to make quick profits. This was because Rentenmarks were not official legal money.

On November 16, 1923, the new Rentenmark was introduced. It replaced the old, worthless paper marks. Twelve zeros were removed from prices. So, if something cost 1,000,000,000,000 (1 trillion) old marks, it now cost 1 Rentenmark. Prices became stable again.

When the head of the Reichsbank died, Schacht took his place. By November 30, 1923, there were 500 million Rentenmarks in use. This grew to 1.8 billion Rentenmarks by July 1924. The old paper marks were still used, but their value kept falling.

On August 30, 1924, a new money law allowed people to exchange 1 trillion paper marks for one new Reichsmark. The Reichsmark was worth the same as a Rentenmark. By 1924, one dollar was equal to 4.2 Rentenmark.

Getting Value Back

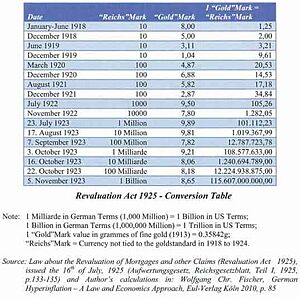

Eventually, some debts were brought back. This was to help people who had lent money before the hyperinflation. A rule in 1925 brought back some mortgages at 25% of their original value in the new money. This was like making them worth 25 billion times their value in the old paper marks. This only applied if the mortgages had been held for at least five years. Some government bonds were also brought back at 2.5% of their value. These would be paid after reparations were finished.

Mortgage debts were brought back at much higher rates than government bonds. Bringing back some debts and restarting taxes in a struggling economy caused many businesses to go bankrupt.

One important part of fixing hyperinflation is "revaluation." This means restoring the value of money that has lost its worth. The German government had to decide between ending hyperinflation quickly or letting problems continue. They argued that they needed to be fair to both those who owed money and those who were owed money.

The government mainly used the US dollar exchange rate and the wholesale price index to figure out the "true" price level during the inflation. They wanted to find the value of the "Goldmark" (the mark before the war).

Finally, a law in 1925 set the conversion rate between the paper mark and the gold mark. This law covered the period from January 1, 1918, to November 30, 1923. The extreme inflation ended the idea that "a mark is worth a mark." This meant the face value of money was no longer always its true value.

This law was challenged in Germany's highest court, the Reichsgericht. But on November 4, 1925, the court ruled that the law was constitutional. This case set an important example for how courts could review laws in Germany.

What Caused It?

Historians and economists don't fully agree on what caused German hyperinflation. They especially debate if reparations payments were the main cause.

The Treaty of Versailles set a large debt for Germany. The London Schedule of Payments in May 1921 set it at 50 billion marks. These payments were partly in goods like coal and timber, and partly in gold and cash. From June 1921 until 1924, Germany made only small cash payments. However, they continued some payments in goods. For example, in November 1921, Germany only paid 13 million gold marks out of 300 million due.

Germany's leaders claimed that they had no gold left. They said inflation happened because they tried to buy foreign money with German money to make cash reparations payments. This would make the German mark lose value quickly.

British and French experts believed German leaders were purposely causing inflation. They thought Germany wanted to avoid paying reparations and making budget changes. Later records showed that tax reform and currency stabilization were delayed in 1922-23. This was done hoping that reparations would be reduced. Allied analysis showed that Germany was printing money to keep taxes low. They also spent a lot of money, and money was leaving Germany quickly. Reparations payments continued fully from 1924 to 1931 without hyperinflation returning. Inflation also helped the German government pay off its huge war debts with money that was worth very little.

One thing historians agree on is that printing money for striking workers in the Ruhr made hyperinflation worse. These workers were refusing to deliver reparations to the Allies. The occupation of the Ruhr also caused Germany's production to drop.

No matter the reason for the mark's falling value, it caused prices to rise very fast. This made it more expensive for the German government to operate. They couldn't raise taxes because taxes would be paid in the ever-falling German currency. So, they printed more money or issued bonds. This put more German marks into the market, making the currency's price fall even more. When Germans realized their money was losing value fast, they tried to spend it quickly. This faster spending made prices rise even faster, creating a vicious cycle.

The government and banks faced a tough choice. If they stopped inflation, there would be immediate bankruptcies, job losses, strikes, hunger, and possibly even revolution. If they continued inflation, they would fail to pay their foreign debts. In the end, trying to avoid both problems failed, and Germany faced both.

What Happened Next

The hyperinflation in Germany in the early 1920s was not the first time this happened. But it has been studied the most by experts. Many strange economic behaviors seen during hyperinflation were first written down during this time. These include prices and interest rates rising incredibly fast. Also, people stopped using cash and bought things like land or gold instead.

Since this hyperinflation, German money policy has always focused on keeping the currency strong. This idea even affected how Germany handled the European sovereign debt crisis. Many Germans mix up the Weimar Republic hyperinflation with the Great Depression. They see them as one big economic crisis with both rising prices and many people losing jobs.

The worthless, hyperinflated marks became popular collector's items in other countries. In 1924, a newspaper estimated that more of these old notes were in the US than in Germany.

Businesses changed how they worked during the crisis. They focused on what was most important to keep running. At first, they changed how they sold and bought things. They also changed how they reported money and used more non-money information. As inflation got faster, people were moved to the most important jobs, especially those dealing with paying workers. Some accounting systems broke down, but new ideas also appeared.

See also

- Andreas Hermes

- Zero stroke

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |