International Bureau of Weights and Measures facts for kids

|

Bureau International des Poids et Mesures

|

|

|

|

Pavillon de Breteuil in 2017

|

|

| Abbreviation | BIPM (from French name) |

|---|---|

| Formation | 20 May 1875 |

| Type | Intergovernmental |

| Location |

|

|

Region served

|

Worldwide |

|

Membership

|

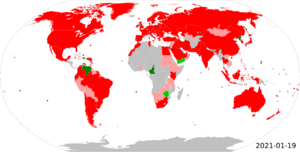

64 member states 37 associate states (see the list) |

|

Official language

|

French and English |

|

Director

|

Martin J. T. Milton |

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) is an organization that helps countries agree on how to measure things. It's like a worldwide referee for measurements! It works with 64 member countries to set standards for things like chemistry, radiation, and even time. The BIPM also helps manage the International System of Units (SI), which is the main system of measurement used around the world.

The BIPM's main office is in the Pavillon de Breteuil in Saint-Cloud, a town near Paris, France.

Contents

What Does the BIPM Do?

The BIPM's main job is to make sure that measurements are the same everywhere. This means that if you measure something in one country, it will be the same measurement in another country. This is super important for science, trade, and everyday life.

Here are some of the BIPM's key activities:

- Creating Guides for Units: They write official guides that explain the International System of Units (SI). This helps everyone understand how to use these units correctly.

- Scientific Research: The BIPM does scientific and technical work in its labs. This includes research in areas like chemistry, radiation, and how we measure time.

- Working Together: They help different countries and groups work together on measurement issues. They also connect with other organizations that support quality and standards.

- Helping Countries Learn: The BIPM has programs to teach and help countries improve their own measurement systems. This is especially helpful for countries that are still developing their science and technology.

- Information Hub: They have a special online library with lots of information and publications about international measurement.

The BIPM is also part of a bigger group called the International Network on Quality Infrastructure (INetQI). This group works to improve quality in areas like measurements, testing, and setting standards.

One very important role of the BIPM is keeping track of the world's time. They collect and combine official atomic time measurements from many countries. This helps them create a single, official time called Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which is used globally.

How the BIPM Is Organized

The BIPM is overseen by a group called the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM). This committee has eighteen members and usually meets twice a year.

Above the CIPM is the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM). This larger group meets in Paris about every four years. It includes representatives from all the member countries and observers from other associated countries. Both the CIPM and CGPM are often called by their French short names.

A Brief History of the BIPM

The idea for the International Bureau of Weights and Measures came about after the Metre Convention was signed in 1875. This happened after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). People realized that countries needed to agree on common ways to measure things.

The need for international standards became clear at the 1855 Paris Exposition. Scientists, especially those who studied the Earth's shape (geodesists), wanted a worldwide office for weights and measures. This led to the 1889 General Conference on Weights and Measures. At this meeting, official copies of the metre and kilogram standards were given to the countries that signed the Metre Convention.

When the metre was first chosen as a unit of length, scientists knew it wasn't exactly what its original definition said. Scientists like Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero worked on remeasuring parts of the Earth to make measurements more accurate. New math methods, like the least squares method, helped them deal with small errors in measurements.

Early Measurement Standards

In the 1800s, units of measurement were often based on unique physical objects. For example, the French standard for length was a special iron ruler called the Toise of Peru. The metre was officially defined by a platinum bar kept in the National Archives. Other copies of the metre were also made.

In 1855, a map of Switzerland that used the metre as its unit of length won a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle. This showed how useful the metre was.

A special measuring device, designed by Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, was shown at an exhibition. This device, called the Spanish Standard, was compared to other important measurement tools. It was very important to control the temperature during these comparisons to avoid errors.

These efforts showed how important scientific methods were for measurements. Scientists like Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero pushed for a worldwide system of measurements.

The Metre and the Struve Geodetic Arc

In 1858, a group in Egypt decided to buy new, precise measuring tools from France. The Spanish Standard was chosen as a model for these new Egyptian tools.

Later, in 1954, a long chain of measurements called the Struve Geodetic Arc was connected to another arc in Africa. This arc, which stretched from Norway to the Black Sea, involved many famous astronomers and scientists. They used copies of the Toise of Peru for their measurements.

These measuring tools often had two different metals, like platinum and brass, fixed together. This helped them account for how materials expand or shrink with temperature changes, making measurements more accurate.

Calls for a Global Standard

In 1866, the Metric Act of 1866 was passed in the United States, allowing the use of the metre. This helped lead to the metre being chosen as the international scientific unit of length.

Scientists realized that old standards, like the Toise of Peru, might be damaged or inaccurate. This was a big concern because if the main standard was unreliable, all copies made from it would also be unreliable.

The International Geodetic Association

The close link between measuring the Earth (geodesy) and setting measurement standards (metrology) meant that the International Association of Geodesy played a big role. This group wanted to combine measurements from different countries to figure out the Earth's exact shape.

They found that different countries used different units of length, which made it hard to compare their measurements. So, leaders like Adolphe Hirsch and Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero suggested choosing the metre as the main unit for geodesy. They also proposed creating an international prototype metre that would be very close to the original mètre des Archives.

In 1867, the International Association of Geodesy suggested adopting the metre and creating an International Metre Commission. This was the first step towards creating the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.

The International Metre Commission

In 1869, the Russian Academy of Sciences asked the French Academy of Sciences to work together to make the metric system used in all scientific work. This led to Napoleon III inviting countries to join the International Metre Commission.

The International Metre Commission met in Paris in 1870 and again in 1872. About thirty countries took part. They discussed whether to keep the existing metre standards or try to make new ones that perfectly matched the metre's original definition (one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator).

They decided to keep the existing standards as the official definition. This was important because changing the definition every time measurements improved would cause chaos. So, the Commission called for a new international prototype metre. This new metre would be as close as possible to the Mètre des Archives, and national standards could be compared to it.

In 1872, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero was chosen as president of the Permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission. In 1874, a large amount of platinum-iridium metal was cast to make new national prototype metres. However, there were problems with impurities in the metal. Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero worked with the French Academy of Sciences to push for the creation of a new International Bureau of Weights and Measures. This new bureau would have the scientific tools needed to redefine units as science advanced.

The 1875 Metre Convention and the Founding of the BIPM

The main goals of the 1875 conference were to replace the old metre and kilogram standards held by the French government. They also wanted to create an organization to manage these standards worldwide. The conference focused only on length and mass units.

Even though France had lost control of the metric system, they made sure that the new international headquarters would be in Paris. This was a way for France to keep an important role.

Key figures like Wilhelm Julius Foerster from Germany and Adolphe Hirsch from Switzerland helped make the Metre Convention happen. They pushed for a permanent International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Spain also strongly supported France in this outcome.

The Metre Convention was signed on May 20, 1875, in Paris. This officially created the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). It was placed under the supervision of the International Committee for Weights and Measures, with Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero as its first president.

The 1889 General Conference

In 1889, the General Conference on Weights and Measures met at the Pavillon de Breteuil, which is where the BIPM is located. At this meeting, they approved and distributed new, very precise prototype standards of the metre and kilogram to the member countries. This helped spread the metric system around the world.

Measuring temperature accurately was very important for length measurements. Scientists knew that even the presence of an observer could affect temperature readings. So, the countries also received special thermometers to ensure accurate length measurements. The new international prototype metre was a "line standard," meaning the metre was defined by the distance between two lines marked on the bar. This helped avoid problems with wear and tear that could happen with "end standards."

Comparing these new metre prototypes required special equipment and a way to define a consistent temperature scale. The BIPM's work on temperature led to the discovery of special metal alloys, like invar. Invar hardly changes length with temperature, which made measuring baselines much simpler. For this discovery, the BIPM's director, Charles Édouard Guillaume, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920. This Nobel Prize showed that metrology was becoming its own scientific field, separate from geodesy.

BIPM and Timekeeping

In 1987, the BIPM took over some of the important work of the International Time Bureau, which was closing down. This included maintaining accurate worldwide time.

Scientists discovered in 1936 that the Earth's rotation isn't perfectly steady. This meant that using the Earth's spin to tell time wasn't precise enough. In 1967, the second was redefined based on atomic clocks. This led to the creation of International Atomic Time (TAI). The BIPM then started setting up atomic clocks around the world. Today, there are more than 450 such clocks that the BIPM uses to keep time.

The 2019 Update of the SI

The International System of Units (SI), which is the modern version of the metric system, was updated in 2019. It is the official system of measurement in almost every country.

The SI system has seven basic units:

- Second (s) for time

- Metre (m) for length

- Kilogram (kg) for mass

- Ampere (A) for electric current

- Kelvin (K) for temperature

- Mole (mol) for amount of substance

- Candela (cd) for light intensity

Since 2019, the exact values of all SI units are defined by seven "defining constants." These are fundamental constants of nature, like the speed of light and the Planck constant. This makes the definitions of the units more stable and precise.

Directors of the BIPM

Here are the people who have led the BIPM since it was founded:

| Name | Country | Term | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilbert Govi | Italy | 1875–1877 | |

| J. Pernet | Switzerland | 1877–1879 | Acting director |

| Ole Jacob Broch | Norway | 1879–1889 | |

| J.-René Benoît | France | 1889–1915 | |

| Charles Édouard Guillaume | Switzerland | 1915–1936 | |

| Albert Pérard | France | 1936–1951 | |

| Charles Volet | Switzerland | 1951–1961 | Honorary director |

| Jean Terrien | France | 1962–1977 | |

| Pierre Giacomo | France | 1978–1988 | |

| Terry J. Quinn | United Kingdom | 1988–2003 | Honorary director |

| Andrew J. Wallard | United Kingdom | 2004–2010 | Honorary director |

| Michael Kühne | Germany | 2011–2012 | |

| Martin J. T. Milton | United Kingdom | 2013–present |

See also

In Spanish: Oficina Internacional de Pesas y Medidas para niños

In Spanish: Oficina Internacional de Pesas y Medidas para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |