Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero

|

|

|---|---|

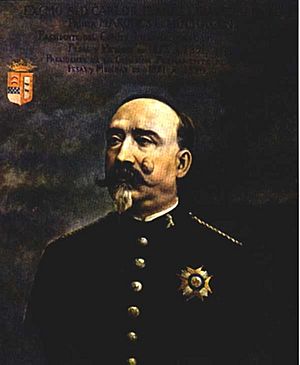

Portrait of Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero in 1881

|

|

| Born | 14 April 1825 Barcelona (Spain)

|

| Died | 28 or 29 January 1891 Nice (France)

|

| Resting place | Cimetière du Château in Nice |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Known for | President of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (1875–1891) |

| Awards | Poncelet Prize |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Geodesy, Geography, Metrology, Statistics. |

| Institutions | Instituto Geográfico Nacional (Spain)

International Association of Geodesy International Statistical Institute |

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero (born April 14, 1825 – died January 28 or 29, 1891) was a Spanish general and a brilliant scientist. He was known as a geodesist, someone who studies the Earth's shape and size. He played a huge role in spreading the metric system around the world. He even helped create the first official international standard for the metre! These standards were used until 1960.

He was born in Barcelona, Spain. His full name came from his parents' surnames, which were very similar. This is why he was often called Ibáñez or Ibáñez de Ibero. He was also known as the 1st Marquis of Mulhacén. He passed away in Nice, France. Because he died around midnight, his exact death date is sometimes listed as January 28th or 29th.

Contents

A Scientist and General

Mapping Spain and Measuring the Earth

Spain started using the metric system in 1849. The government wanted to create a detailed map of Spain. In 1853, Ibáñez was chosen to lead this important project.

He worked with his friend, Captain Frutos Saavedra Meneses, to design new tools. These tools were for measuring long distances very accurately. They improved on older methods by using a single measuring bar with tiny marks. They also found better ways to deal with temperature changes. Temperature can make materials expand or shrink, affecting measurements.

Ibáñez and Saavedra went to Paris to make their new measuring tool. It was called the Spanish Standard. This tool was so good that copies were made for other countries, like Egypt. In 1858, they used the Spanish Standard to measure a key distance in Spain. They did this with amazing precision for their time.

From 1865 to 1868, Ibáñez also mapped the Balearic Islands and connected them to the Iberian Peninsula. He invented an even faster measuring tool for this work. This new tool, called the Ibáñez apparatus, was later used in Switzerland.

In 1870, Ibáñez founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute. He led this institute until 1889. It was one of the largest geographic institutes in the world. It handled everything from mapping to statistics and weights and measures.

Connecting Continents: Measuring the Paris Meridian

Ibáñez's measuring tools were so important that copies were made for France and Germany. These tools helped with major mapping projects across Europe. One big project was extending the Paris meridian (an imaginary line from the North Pole to the South Pole, passing through Paris).

Earlier measurements of this meridian had some errors. So, in 1865, Spain joined France and Portugal to re-measure and extend it. From 1870 to 1894, Ibáñez and French scientists worked on this.

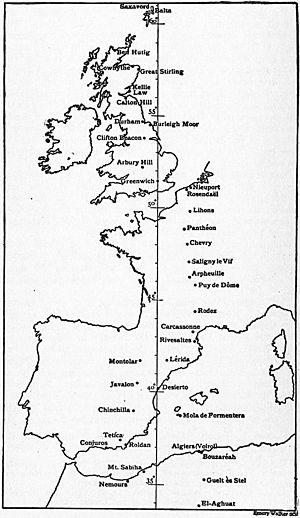

In 1879, Ibáñez and François Perrier connected the mapping networks of Spain and Algeria. This was a huge achievement! It meant they had measured a meridian arc stretching from Shetland (north of Scotland) all the way to the Sahara Desert.

This connection involved measuring across the Mediterranean Sea. They used mountain stations like Mulhacén and Tetica to observe triangles up to 270 kilometers long. This project helped scientists better understand the true shape of the Earth.

Working Together for a World Standard

In 1866, Spain, represented by Ibáñez, joined a group called the Central European Arc Measurement. This group later became the International Association of Geodesy. In 1867, they discussed creating an international standard for length. This was important so that measurements from different countries could be easily compared.

They suggested using the metre as the international standard. They also proposed creating an international commission for the metre. Ibáñez was a key part of these discussions.

In 1869, the French government invited countries to join the International Metre Commission. Spain accepted, and Ibáñez became president of its Permanent Committee in 1872. He represented Spain at the 1875 Metre Convention and the first General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1889.

He was also elected Chairman of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (1875–1891). For his work in spreading the metric system, he received the Légion d'Honneur. He also won the Poncelet Prize for his scientific contributions.

Ibáñez explained that the new international metre would be a physical object. It would no longer be based on the Earth's dimensions. Instead, it would be the main unit for a new international system of measurements.

The International Geodetic Association decided to create an international measuring tool. This tool would be used to measure new distances or re-measure old ones. It would be calibrated at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). This would ensure all measurements were based on the same standard.

The 1875 conference also discussed the best way to measure gravity. Gravity measurements help us understand the Earth's shape. They decided to use a special tool called a reversion pendulum.

Ibáñez became the first president of the International Association of Geodesy in 1887. Under his leadership, the association grew to include countries like the United States, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and Japan.

The progress in measuring tools (metrology) and gravity (gravimetry) changed geodesy. Scientists realized they needed one single unit for all measurements. This unit had to be accepted by all countries.

Scientists also learned about different types of errors in measurements. Some errors are random, and some are constant (systematic). Systematic errors are very important to avoid. They can make observations wrong in a consistent way. So, it was crucial to compare all measuring tools and pendulums with great precision. This would allow geodesists to link all the work from different nations.

In 1889, the General Conference on Weights and Measures met. They approved and distributed new, incredibly precise metre standards. These prototypes were made of a special platinum-iridium alloy. This material was chosen because it was hard, permanent, and resistant to chemicals. These qualities made it perfect for standards that needed to last for centuries.

The BIPM also worked on measuring temperature. This led to the discovery of special alloys like invar. The director of BIPM, Charles-Édouard Guillaume, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920 for this discovery. Invar wires made measuring long distances much faster and easier.

Later Life and Family

In 1889, Ibáñez had a stroke. He then resigned from leading the Institute of Geography and Statistics. He had directed it for 19 years.

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero married Jeanne Baboulène Thénié in 1861. They had a daughter. He later married Cécilia Grandchamp in 1878, and they had a son, Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero Grandchamp. After Ibáñez's death, his two children and Cécilia settled in Geneva, Switzerland.

His son, Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero Grandchamp, became an engineer and a doctor. He founded the Institute of Hispanic Studies in Paris in 1913. This institute is now part of Sorbonne University.

Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero's eldest daughter, Elena Ibáñez de Ibero, married a Swiss lawyer. The title of Marquis of Mulhacén passed to their son and then to their grandson.

His Lasting Impact

Carlos Ibáñez's work was part of a long effort to create a universal system of measurement. The metric system was designed to be "for all times, for all peoples."

Early measurements of the metre had some challenges. For example, the first measurements of the Paris meridian by French astronomers Delambre and Méchain had small errors. These errors were due to problems with their instruments and the Earth's irregular shape.

However, scientists like Ibáñez, using new methods like the "least squares method," helped to correct these errors. This method helps to find the best fit for data even when there are small measurement errors. This showed how important scientific methods and statistics were in geodesy. Ibáñez was one of the first members of the International Statistical Institute.

One of Ibáñez's most amazing achievements was connecting the mapping networks of Spain and Algeria across the Mediterranean Sea. Because of this, the Spanish government gave him the title of 1st Marquis of Mulhacén. This honored his brilliant work and how he raised Spain's standing among other nations.

Unfortunately, the Paris meridian was later replaced as the main reference line. In 1884, the International Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C. chose the Greenwich meridian as the world's prime meridian. Spain adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1901.

Later, new technologies like wireless telegraphy helped to unify time around the world. The International Time Bureau was created to manage this. Over time, the definition of the second also changed. It moved from being based on the Earth's rotation to being based on atomic clocks.

Today, the International System of Units (SI) is the modern form of the metric system. It is used in almost every country. It has seven basic units, including the metre for length and the second for time. These units are now defined by exact values of fundamental constants of nature. This means they are incredibly precise and universal, thanks to the pioneering work of scientists like Carlos Ibáñez.

See also

In Spanish: Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero para niños

In Spanish: Carlos Ibáñez de Ibero para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |