History of geodesy facts for kids

The history of geodesy is all about how people figured out the shape and size of our planet, Earth. It started way back in ancient times and really grew during the Age of Enlightenment, a period when new ideas and scientific discoveries were booming.

For a long time, many people thought the Earth was flat, like a pancake, with the sky as a big dome over it. But smart thinkers eventually noticed clues that suggested Earth was actually round. For example, during a lunar eclipse, the Earth's shadow on the Moon is always round. Also, as travelers went south, they saw the North Star appear lower in the sky. These observations helped people realize Earth was a sphere.

Contents

Ancient Greek Discoveries

Early Ideas About Earth's Shape

The first written records about a spherical Earth come from ancient Greek sources. We don't know exactly how they first thought of it, but it might have been from travelers. People noticed that as they moved around the Mediterranean Sea, especially between the Nile Delta and Crimea, the stars they could see in the sky changed. This suggested a curved surface.

Some historians also think that ancient Phoenician sailors might have had an idea of a round Earth. These skilled sailors were said to have sailed all the way around Africa around 610–595 BC. The historian Herodotus wrote about this journey, mentioning that the sailors saw the Sun on their right side when sailing clockwise around Africa. This detail makes modern historians think the story is true. It's possible this amazing journey inspired the idea of a spherical Earth, first mentioned by the philosopher Parmenides.

Early Greek philosophers had different ideas. Homer thought Earth was a flat disc. Anaximenes believed it was rectangular. But others, like Pythagoras (who was a mathematician), might have thought it was a perfect sphere. By the 5th century BC, most respected Greek writers believed the world was round.

Plato's View of a Round Earth

Plato (427–347 BC) was a famous Greek philosopher. He studied mathematics and, like Pythagoras, taught his students that Earth was a sphere. He didn't explain how he knew this, but he said, "My conviction is that the Earth is a round body in the centre of the heavens." He even imagined that if you could fly high above the clouds, Earth would look like a colorful ball.

Aristotle's Proofs for a Spherical Earth

Aristotle (384–322 BC) was one of Plato's best students. He provided strong reasons why Earth must be a sphere. He noticed that certain stars visible in Egypt and Cyprus could not be seen in northern areas. This could only happen if the Earth's surface was curved. He also pointed out that the shadow Earth casts on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is always round.

Aristotle also believed that all parts of Earth naturally pull towards the center, forming a sphere. He estimated the Earth's circumference to be about 74,000 km (45,000 miles), which was much larger than the actual size (about 40,000 km).

He also divided the world into five climate zones: two cold zones near the poles, two mild zones, and a hot zone near the equator. Aristotle's ideas about a spherical Earth at the center of the universe (geocentric model) were very influential for many centuries.

Archimedes and Fluid Surfaces

Archimedes, a brilliant Greek mathematician, also contributed to understanding Earth's shape. He showed that the surface of any still fluid, like water, forms a sphere. He used this idea to support the belief that Earth itself is a sphere.

Eratosthenes Measures Earth's Size

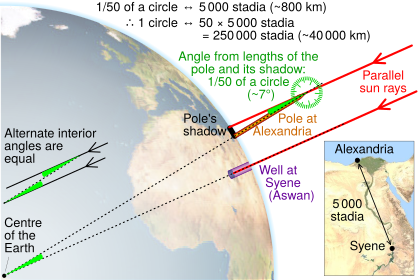

Around 240 BC, a Greek astronomer named Eratosthenes (276–194 BC) made a very clever estimate of Earth's circumference. He lived in Alexandria, Egypt. His method was lost, but a simplified version was described by Cleomedes.

Eratosthenes knew that in the city of Syene (modern Assuan), the Sun was directly overhead at noon on the summer solstice (the longest day of the year). This meant a vertical stick would cast no shadow. In Alexandria, which was north of Syene, a stick would cast a shadow at the same time. He measured the angle of this shadow to be about 7 degrees.

He knew the distance between Syene and Alexandria was about 5,000 stadia (an ancient unit of length). Since 7 degrees is about 1/50th of a full circle (360 degrees), he multiplied 5,000 stadia by 50 to get Earth's circumference: 250,000 stadia. If one stadium was about 157.5 meters, his result was about 39,375 km, which is very close to the actual circumference of about 40,075 km!

Interestingly, 1,700 years later, Christopher Columbus studied Eratosthenes' work. But he chose to believe other maps that showed Earth was much smaller. If Columbus had trusted Eratosthenes' accurate measurements, he might not have tried to sail west to Asia, because he wouldn't have had enough supplies for such a long journey.

Other Greek Thinkers

Seleucus of Seleucia (around 190 BC) also believed Earth was spherical and even thought it orbited the Sun, like Aristarchus of Samos had suggested.

Another Greek scholar, Posidonius (c. 135–51 BC), also tried to measure Earth's size. He used the star Canopus, which was barely visible from Rhodes but hidden in most of Greece. He estimated the angle and, using the distance from Alexandria to Rhodes, calculated a circumference of 240,000 stadia. Later, his estimate was changed to 180,000 stadia. These different estimates were used by Claudius Ptolemy in his maps.

Ancient India's Contributions

Ancient Indian astronomers also developed their own ideas about the Earth. While some early texts don't survive, their accurate predictions of the Moon and Sun's movements suggest they made careful observations.

Aryabhata's Spherical Earth Model

The Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata (476–550 CE) was a very important figure. In his book Āryabhaṭīya, written in Sanskrit, he described Earth as spherical and stated that it rotates on its own axis from west to east.

He explained why heavenly bodies seem to move from east to west: "Just as a passenger in a boat moving downstream sees the stationary (trees on the river banks) as traversing upstream, so does an observer on earth see the fixed stars as moving towards the west at exactly the same speed (at which the earth moves from west to east)."

Aryabhata also estimated Earth's circumference. He gave it as 4967 yojanas. If one yojana is about 8 km, his estimate was around 39,736 km, which is very close to the actual equatorial circumference of 40,075 km.

Roman Empire's Understanding

The idea of a spherical Earth slowly spread. In the West, the Romans learned about it from the Greeks. Many Roman writers, like Cicero and Pliny, mentioned Earth's roundness as a known fact. Pliny even thought it might be slightly imperfect, "shaped like a pinecone."

Strabo and Seafarers' Observations

The geographer Strabo (c. 64 BC – 24 AD) suggested that sailors probably had the first real evidence that Earth wasn't flat. They noticed that when a ship sailed away, its lower parts disappeared first, and then the mast and sails. Also, elevated land or lights were visible from farther away than lower ones. This showed the curvature of the sea.

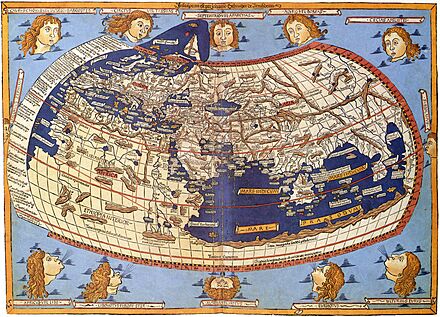

Claudius Ptolemy's Detailed Maps

Claudius Ptolemy (90–168 AD), who lived in Alexandria, was a very important astronomer and geographer. In his major work, the Almagest, he gave many reasons for Earth's spherical shape. He noted that when a ship sails towards mountains, they seem to "rise from the sea," meaning they were hidden by the curved surface. He also argued that Earth is curved both north-south and east-west.

Ptolemy also created an eight-volume book called Geographia, which was a huge collection of what was known about Earth. He assigned coordinates (like latitude and longitude) to many places, creating a grid for the globe. His maps showed the known world stretching from the Canary Islands in the Atlantic Ocean all the way to China. He knew he only had information about about a quarter of the globe.

Late Antiquity and Early Christianity

By Late Antiquity, the idea of a spherical Earth was generally accepted by scholars, including early Christian thinkers. While a few early Christian scholars, like Lactantius, questioned it based on a literal reading of the Hebrew Bible, most learned Christians, like Augustine of Hippo, knew Earth was spherical. The idea of a flat Earth mostly disappeared by the 7th century.

Writers like Macrobius and Martianus Capella (both 5th century AD) discussed Earth's circumference, its central place in the universe, and how seasons differ in the northern and southern hemispheres.

Islamic World's Advancements

Islamic astronomy built upon the Greek idea of a spherical Earth. Muslim mathematicians developed spherical trigonometry, a type of math used for calculations on curved surfaces. This was important for finding the distance and direction to Mecca (the Qibla), which Muslims face during prayer.

Caliph Al-Ma'mun's Measurement

Around 830 CE, the Caliph al-Ma'mun ordered a group of Muslim astronomers and geographers to measure the distance of one degree of latitude. They did this by measuring the distance traveled north or south on flat desert land until the angle of the North Pole changed by one degree. Their estimate for Earth's circumference was very close to modern values, around 40,248 km.

Al-Farghānī and Columbus's Error

Al-Farghānī (also known as Alfraganus) was a Persian astronomer who helped measure Earth's diameter for Al-Ma'mun. His estimate for a degree was much more accurate than Ptolemy's. However, Christopher Columbus later mistakenly used Alfraganus's measurement as if it were in Roman miles instead of Arabic miles. This made him think Earth was much smaller than it actually was, which encouraged his famous voyage.

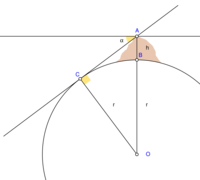

Al-Biruni's Clever Method

Abu Rayhan Biruni (973–1048) developed a new and clever way to measure Earth's circumference. Instead of needing two locations, he used trigonometric calculations from the top of a mountain. He measured the angle of the horizon from the mountain peak and, knowing the mountain's height, he could calculate Earth's curvature. This method allowed a single person to measure Earth's size from one spot. He estimated Earth's radius to be about 6,339.6 km, which is very close to the actual value.

Medieval Europe's Knowledge

Greek Influence in Europe

In medieval Europe, the knowledge of Earth's spherical shape continued through Greek texts, and through writers like Isidore of Seville and the Venerable Bede. As learning grew in medieval universities, this idea became more widely known.

The spread of this knowledge was gradual, often linked to the spread of Christianity. For example, the first evidence of a spherical Earth in Scandinavia comes from a 12th-century translation of a book called Elucidarium. Many writers from Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages knew Earth was spherical.

Early Medieval European Views

Bishop Isidore of Seville (560–636) wrote in his encyclopedia that Earth was "round." While his exact meaning has been debated, many scholars believe he meant spherical.

The monk Bede (c. 672–735) clearly stated in his book The Reckoning of Time that Earth was round. He wrote, "We call the earth a globe... For truly it is an orb placed in the centre of the universe; in its width it is like a circle, and not circular like a shield but rather like a ball." His book was widely copied, meaning many priests learned about Earth's sphericity.

High and Late Medieval Europe

During the High Middle Ages, European knowledge of astronomy grew, partly from learning shared by Islamic scholars.

Johannes de Sacrobosco (c. 1195–c. 1256 AD) wrote an important astronomy book called Tractatus de Sphaera. It included clear proofs that Earth is spherical. Historians note that no one who studied at a medieval university believed Earth was flat.

Even in popular writings, like Dante's Divine Comedy (early 14th century), Earth is shown as a sphere. Dante discussed things like different stars being visible in the southern hemisphere and different time zones. This shows that the idea of a spherical Earth was well-known even outside of academic circles.

Early Modern Period Discoveries

Ming China's Understanding

In China, the scholar Shen Kuo (1031-1095) used observations of lunar and solar eclipses to conclude that celestial bodies were round. He explained that the Moon's phases (waxing and waning) showed it was a sphere reflecting sunlight. However, his ideas about Earth's shape didn't become widely accepted in China at the time.

In the 17th century, Jesuit missionaries from Europe, who were skilled astronomers, came to China. They successfully showed the Chinese that Earth was spherical, challenging the traditional Chinese belief that Earth was flat and square. A Chinese book from 1648 even showed a picture of Earth as a globe, stating that "the round Earth certainly has no square corners."

Sailing Around the World

The Age of Discovery, with voyages by explorers like Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan, provided more direct proof of Earth's size and shape.

The most direct proof came from the Magellan expedition, the first time anyone sailed all the way around the world. Led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, five ships left Seville in 1519. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean, sailed through the Strait of Magellan, and then crossed the Pacific. Magellan was killed in the Philippines, but his second-in-command, Juan Sebastián Elcano, continued the journey and returned to Seville in 1522, completing the circumnavigation.

While sailing around the world doesn't *only* prove Earth is spherical (it could be a cylinder, for example), combined with all the other evidence, Magellan's journey removed any remaining doubts in educated circles in Europe.

European Calculations of Earth's Shape

In the 17th century, new tools like the telescope and theodolite (for measuring angles) and logarithm tables (for calculations) allowed for more precise measurements of Earth.

In 1669–1670, Jean Picard performed the first modern measurement of a meridian arc (a line of longitude). Later, Gian Domenico Cassini and his son Jacques Cassini extended Picard's measurement. They found that the length of one degree of latitude in the northern part of their measurement was shorter than in the southern part. This suggested Earth was a prolate spheroid (taller than wide), which contradicted Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens's theories that Earth should be an oblate spheroid (wider at the equator, flattened at the poles) due to its rotation.

To solve this, the French Academy of Sciences sent two expeditions in the 1730s. One went to the far north (near the Arctic), and the other went to Ecuador (near the equator). Their measurements proved that Earth is indeed an oblate spheroid, wider at the equator and slightly flattened at the poles. This became the new standard shape for Earth.

In the 19th century, more precise surveys were done. The Struve Geodetic Arc, a chain of survey points nearly 3,000 km long across Scandinavia and Russia, was one of the most accurate projects of its time. It further refined the measurements of Earth's shape and size.

Modern Geodesy and Mathematics

The science of geodesy continued to advance with new mathematical tools. Carl Friedrich Gauss developed the method of least squares, which is used to find the best fit for data, helping to reduce errors in measurements. Friedrich Bessel also made important contributions, including studying the effect of gravity on pendulums to determine Earth's shape.

By the late 19th century, the International Association of Geodesy was formed. This group worked to create a single, accurate model of Earth's shape and gravity for the whole world. They also helped establish the metre as a worldwide standard unit of length. These efforts led to a much more precise understanding of our planet's true shape, which is not a perfect sphere, but a slightly irregular "potato-shaped" figure called a geoid.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la geodesia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la geodesia para niños

- Bedford Level experiment

- Figure of the Earth

- History of the metre

- History of cadastre

- History of cartography

- History of hydrography

- History of navigation

- History of surveying

- Paris meridian § History

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |