Irish Mercantile Marine during World War II facts for kids

During World War II, Irish ships played a super important role. This time was called The Long Watch by Irish sailors. Even though Ireland was neutral (meaning it didn't pick sides in the war), its ships kept bringing in vital goods and sending out food, mostly to Great Britain.

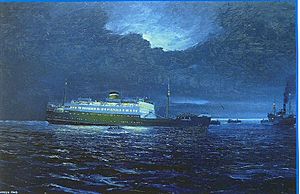

Irish ships sailed without weapons and usually alone. They showed they were neutral by using bright lights at night. They also painted the Irish tricolour flag and the word "EIRE" in big letters on their sides and decks. Even so, about 20 out of every 100 Irish sailors died. They were victims of a war that wasn't theirs. Both sides attacked them, but mostly the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Japan).

Often, Allied (Britain, USA, Soviet Union) convoys (groups of ships) didn't stop to rescue people. But Irish ships often answered SOS calls. They stopped to save survivors, no matter which side they were from. Irish ships bravely rescued 534 sailors during the war.

When World War II started, Ireland declared itself neutral. This period was known as "The Emergency" in Ireland. Ireland became more cut off than ever. Shipping had not been looked after since the Irish War of Independence. Foreign ships, which Ireland used a lot for trade, were harder to find. Neutral American ships would not even enter the "war zone."

In 1940, Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Éamon de Valera said that Ireland was almost completely blocked off. This was because of the fighting countries and Ireland's lack of ships.

Ireland grew more food than it needed. This extra food was sent to Britain. The Irish merchant ships made sure that Irish farm products and other goods reached Britain. They also made sure that British coal came to Ireland. Some foods like wheat, citrus fruits, and tea had to be imported. Ireland mostly relied on British oil tankers for fuel. At first, Irish ships sailed in British convoys. But they soon chose to sail alone, trusting their neutral markings. German respect for Ireland's neutrality changed from friendly to tragic.

The "cross-channel" trade between Ireland and Britain was the most important trade route for both countries. Irish ships also crossed the Atlantic Ocean. They followed a route set by the Allies. Ships on the "Lisbon-run" brought wheat and fruits from Spain and Portugal. They also carried goods that had been transferred from the Americas.

There were never more than 800 men serving on Irish ships at any one time during the war.

Why Ireland Needed Its Own Ships

After Ireland became independent in 1921, the government didn't really help develop its merchant navy. People said, "Our new leaders seemed to turn their backs upon the sea." Each year, the number of ships went down. In 1923, Ireland had 127 merchant ships. By 1939, at the start of World War II, this number had fallen to just 56 ships. Only 5% of imports came on Irish ships.

There were several reasons for this decline. These included the effects of the War of Independence, a policy of trying to be self-sufficient, the Great Depression, and a lack of money invested in shipping. Foreign ships, which Ireland had always relied on, were pulled out of service. Between April 1941 and June 1942, only seven such ships visited Ireland.

The Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) and the Irish Civil War (1921–1922) left Ireland's economy in a very bad state. Factories and roads were destroyed. Many businesses moved to other countries. It was often cheaper to transport goods by sea within Ireland. This was because the roads and railways were in poor condition. To use this chance, new small ships called "coasters" were bought in the 1930s. They were meant to sail between Irish ports. These small ships became very valuable once the war started. Many of these coasters were lost, especially on the "Lisbon run." This was a journey they were never meant to make.

The Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera, wanted Ireland to be self-sufficient. This meant making everything Ireland needed at home. He didn't want many foreign goods to be imported.

The worldwide Great Depression in the early 1930s didn't hit Ireland as hard. This was because Ireland was recovering from the civil war. Also, Irish industries were protected by taxes on foreign goods during the Anglo-Irish Trade War (1932–1938). Other countries' ships easily met Ireland's need for more sea transport. Foreign ships were used instead of keeping the Irish fleet strong. Banks didn't want to lend money to Irish businesses. They preferred to invest in British government bonds.

Even though the government supported many industries, it didn't support shipping. In 1933, de Valera's government started the Turf Development Board. Peat (turf) became Ireland's main fuel during the war years. It was stored up because imported coal was hard to get. In 1935, government workers warned de Valera about how a war would affect fuel imports. He ignored them.

In 1939, people in Ireland suddenly realized how important the sea was to their island country. But by then, Britain had already put limits on shipping because of the war. Historians say that not building up an Irish merchant navy in the 1930s made Ireland's supply problems worse during World War II.

War Begins: Choices for Irish Ships

When World War II started, Ireland declared itself neutral. At that time, Ireland had 56 ships. Another 15 were bought or rented during the war. Sadly, 16 Irish ships were lost. Before the war, most Irish-registered ships flew the British Red Ensign flag. British law required them to do so. But some, like the Wexford Steamship Company ships, always used the Irish tricolour.

When the war began, choices had to be made. The Irish government ordered all Irish ships to fly the tricolour. Some British ships were registered in Ireland. For example, some whaling ships were owned by a Scottish company but registered in Ireland. This was to use Ireland's whale hunting quota. These six whale catchers and two factory ships were transferred to British ownership and used by the British navy.

Some ships that could be called British also chose to fly the tricolour. The Kerrymore, registered to R McGowan of Tralee, was actually owned by Kelly Colliers of Belfast. Most of its crew lived in loyalist areas of Belfast. For six years, they sailed under the tricolour.

The British and Irish Steam Packet Company's Munster, which sailed between Dublin and Liverpool, flew the tricolour. But no flag could protect against mines. The Munster hit a mine near Liverpool and sank. Over 200 passengers and 50 crew were on board. A few hours later, they were all rescued by another ship. Four people were hurt, and one died later.

Other ferries, like Cambria, Hibernia, and Scotia, were Irish-registered. They sailed between Dún Laoghaire and Holyhead under the Red Ensign. Their British crews were surprised when the tricolour was raised. They went on strike and refused to sail. They only agreed when the ships were moved to British registration and the Red Ensign was put back. The Scotia sank during the Dunkirk evacuation, with 30 crew and 300 soldiers lost.

What Irish Ships Carried

| Farm Land Used for Crops | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 1.7 million acres | |||

| 1916 | 1.7 million acres | |||

| 1918 | 2.4 million acres | |||

| 1921 | 1.8 million acres | |||

| 1932 | 1.4 million acres | |||

| 1939 | 1.5 million acres | |||

| 1941 | 2.2 million acres | |||

| 1944 | 2.6 million acres | |||

| 1951 | 1.7 million acres | |||

| 1961 | 1.6 million acres | |||

| How Irish farming changed during World War I and World War II | ||||

Exports: Food for Britain

The main thing Ireland exported was farm produce to Britain.

In World War I, Ireland grew more food to help Britain. This happened again in World War II. In 1916, about 1.7 million acres were used for crops. This went up to 2.4 million acres in 1918. By 1932, it had dropped to 1.4 million acres.

The Anglo-Irish Trade War between Ireland and Britain started in 1932. Britain put a tax on Irish products. Cattle from the Irish Republic were taxed, but cattle from Northern Ireland were not. So, cattle were smuggled across the border. In 1934-35, about 100,000 cattle were "exported" this way. The Irish Department of Supplies even supported the smuggling. By then, Britain wanted to make sure it could get Irish food before another world war.

There were several agreements, like the "cattle-coal pact" of 1935. The Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement of 1938 ended the dispute. These agreements were good for Ireland.

| Item | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle, thousands | 702 | 784 | 636 | 307 | 616 | 453 | 445 | 496 |

| Beef, thousand tons | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 16.2 | 5.7 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 3.9 |

|

There was a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in 1941. |

||||||||

Under the "cattle-coal pact," the British set up a system to buy cattle. Prices before the war were good. As the war went on, market prices went up a lot. Cattle from Northern Ireland got better prices, so smuggling started again.

To meet the demand for food in World War II, the area of land used for crops grew. It went from 1.5 million acres in 1939 to 2.6 million acres in 1944. It's hard to say exactly how important Irish food exports were to Britain. This is because of smuggling, unreliable numbers, and wartime censorship. While Ireland's food production increased, British food imports decreased. For example, the UK imported 1.36 million tons of food in August 1941, but only 674,000 tons in August 1942.

| year | Ireland | Britain | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934/38 | 3,109 | 3,042 | 2,714 | 2,921 |

| 1946/47 | 3,059 | 2,854 | 2,424 | 1,980 |

Before and during World War II, Ireland exported more food than it imported. Irish people had a high-calorie diet. (However, poor people still faced real hardship.) Food was even given to war refugees in Spain. Ireland did need to import some foods, like fruits, tea, and wheat. Nearly half of Ireland's wheat came from Canada. Growing food in Ireland relied on imported fertilizer and animal feed. In 1940, 74,000 tons of fertilizer were imported. Only 7,000 tons arrived in 1941. Similarly, 5 million tons of animal feed came in 1940, falling to one million in 1941, and almost none after that.

Imports: What Ireland Needed

Even though Ireland had extra food, some foods couldn't be grown there because of the climate. Only small amounts of wheat were grown. The government ordered farmers to grow more crops. If they didn't plant wheat, their land could be taken away. In 1939, 235,000 acres of wheat were planted. By 1945, this had increased to 662,000 acres. But there was still not enough, and imports were needed.

Fights between smugglers and customs officers were common. In 1940, the "Battle of Dowra" happened on the border of counties Leitrim and Fermanagh. Customs crews stopped over a hundred men with donkey loads of smuggled flour. The smugglers didn't want to give up their goods. They used clubs, boots, stones, and fists in the fight. Most of the flour was destroyed, and some customs officers were hurt.

In early 1942, the Allies limited wheat deliveries to Ireland. In return, the Irish threatened to stop exporting Guinness beer. To the annoyance of the US Ambassador, Ireland received 30,000 tons of wheat. The Ambassador complained it was a waste of "a vital necessity for what Americans regard at the best as a luxury and at worst a poison."

By 1944–45, coal imports were only one-third of what they were in 1938-39. Oil supplies had almost stopped. The making of "town gas" from imported coal was so badly affected that rules were made to limit its use. These were enforced by the "Glimmer Man." Britain eased these rules from July 19, 1944.

There were plans to build an oil refinery in Dublin, but it was never finished. However, seven oil tankers were built in Germany for Inver Tankers Ltd. Each was about 500 feet long and could carry 500 tons. They were registered in Ireland.

Britain asked Ireland to take control of these tankers. Ireland said it was not its policy to take control of ships. Instead, it offered to transfer them to British registration. This happened on September 6, just three days after war was declared. Two days after the transfer, on September 11, 1939, while still flying the Irish tricolour, the Inverliffey was sunk. Even though Captain William Trowsdale said they were Irish, the German U-boat said they were sorry but would sink the Inverliffey. This was because it was carrying petrol to England, which the Germans saw as illegal goods.

The U-boat's next encounter with the Irish tricolour was less polite. The U-boat shelled the fishing trawler Leukos. All 11 crew members were lost. Inver Tankers lost its entire fleet during the war.

U-boat Encounters

Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, the commander of German U-boats, gave an order on September 4, 1940. It said which countries were fighting, neutral, or friendly. It specifically mentioned Ireland as neutral. The order ended by saying: "Ireland forbids warships in its waters. This rule must be strictly followed to protect Ireland's neutrality." However, these orders did not always protect Irish ships.

There were many meetings with U-boats, some friendly, others not. On March 16, 1942, the Estonian ship Irish Willow, leased to Irish Shipping, was stopped by a German U-boat. The U-boat signaled, "Send master and ship's papers." The Chief Officer, Harry Cullen, and four crew members rowed to the U-boat. He said his captain was too old for the boat. He also added that it would be Saint Patrick's Day in the morning. They were given a drink and a bottle of brandy to take back to Irish Willow. Later, Irish Willow bravely rescued 47 British sailors from another ship.

On March 20, 1943, another German U-boat stopped the Irish Elm. The sea was too rough for the Elms crew to row to the submarine. So, they talked by shouting. The Elms Chief Officer, Patrick Hennessy, said his home was Dún Laoghaire. The U-boat commander asked if "the strike was still on in Downey's," a pub near Dún Laoghaire harbour. (The Downey's strike had started in March 1939 and lasted 14 years.)

Sailing in Convoys

Irish and British officials worked together to rent ships. They also bought wheat, corn, sugar, animal feed, and petrol together. At the start of the war, Irish ships joined convoys. These were groups of ships protected by the Royal Navy. The idea was that this would offer protection and cheaper insurance. But this didn't always work out. So, Irish ships chose to sail alone.

Being able to insure ships, cargo, and crew is very important for shipping profits. Insuring Irish ships during "The Long Watch" was difficult. One big problem was that Irish ships usually didn't travel in convoys. Insurance companies like Lloyd's of London charged more to insure ships not in a convoy.

For example, the crew of the City of Waterford faced insurance problems. When this ship joined Convoy OG 74, the crew's lives were insured. The ship crashed with a Dutch tugboat and sank. The Waterfords crew was rescued by a British warship. Then they were moved to a rescue ship. This rescue ship was bombed two days later. Five of the City of Waterfords survivors died. When their families claimed life insurance, they were refused. This was because at the time of their death, they were not crew of the City of Waterford, but passengers on the other ship. Later, the Irish government started a payment plan for sailors lost or hurt on Irish ships. Irish Shipping also started its own insurance company, which made a good profit.

Two ships from the Limerick Steamship Company, Lanahrone and Clonlara, were part of the "nightmare convoy" OG 71. This convoy left Liverpool on August 13, 1941. As neutral ships, the Limerick ships had no blackout lights. The British convoy leader worried this would make the convoy easy to see at night. The vice admiral put the two Irish ships in the middle of the convoy to try and make them less visible.

On August 19, a Norwegian destroyer was sunk by a German U-boat. Three minutes later, another U-boat sank a British merchant ship. The Clonlara rescued 13 survivors from that ship. Two hours later, two more ships were sunk. Two days later, the Clonlara was sunk. Another British warship rescued 13 survivors (eight from Clonlara, five from the first ship). Eight merchant ships, two naval escort ships, and over 400 lives were lost in this convoy.

Five of the convoy's remaining merchant ships reached Gibraltar. Ten went back to neutral Portugal. This was seen as a "bitter act of surrender." In Lisbon, the Lanahrones crew went on strike. It was settled with extra life-rafts and better pay. The crew of the Irish Poplar was waiting in Lisbon. When the damaged ships from OG 71 arrived, the Irish Poplars crew decided to sail home alone.

These experiences and the Royal Navy's inability to protect merchant ships deeply affected all Irish ships. After this, they turned off their lights when sailing in Allied convoys. Ship owners, following their captains' advice, decided not to sail their ships in British convoys. By early 1942, this practice had stopped.

Captain William Henderson of the Irish Elm, returning from a trip across the Atlantic, reported being "circled by two German bombers." He said they "inspected closely but didn't bother" them. This made the crew feel very confident that their neutral markings protected them.

Important Trade Routes

Trade with Britain

This "cross-channel" trade was most of Ireland's trade. The ships varied greatly in age. The newest was Dundalk, built in 1937, and the oldest was Brooklands, built in 1859. The most important ships for Ireland were the ten coal ships. For Britain, the most important were the ships carrying livestock. At first, Germany respected Irish ships' neutrality. They even apologized for the first attack on the coal ship Kerry Head and paid for the damage. Losses mostly came from mines, not direct attacks. The Meath suffered this fate. While being checked by the British Naval Control Service, she hit a magnetic mine. Seven hundred cattle drowned, and both ships were destroyed.

In August 1940, Germany "demanded" that Ireland stop sending food to Britain. On August 17, 1940, Germany declared a large area around Britain a "war zone." It was believed that attacks on Irish ships and the bombing of Campile were to make this point clear. Lord Haw-Haw, a German radio broadcaster, threatened that Dundalk would be bombed if cattle exports to Britain continued. On July 24, 1941, George's Quay in Dundalk was bombed. Still, the trade continued.

The first attack after the German warning was on the schooner Lock Ryan. She was returning to Arklow when three German planes attacked her with machine guns and bombs. Luckily, Lock Ryan's cargo of china clay absorbed the blast. Although badly damaged, she survived. Germany admitted the attack but refused to pay for the damage. They said she was in "the blockaded area," where Ireland had been offered free passage but refused the terms. There were many attacks on ships in the cross-channel trade. In 1940, nine Irish ships were lost. This number might seem small compared to Allied losses, but it was a large part of the small Irish fleet.

There were rules about reporting ship attacks. Frank Aiken, the Minister in charge of censorship, changed this policy. He wanted Germany to know that the Irish public knew about the attacks, and "they don't like it." Deliberate attacks on cross-channel shipping stopped on November 5, 1941. Mines remained a constant danger.

The Iberian Trade: The Lisbon Run

In November 1939, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed a law that stopped American ships from entering the "war zone." This zone was a line from Spain to Iceland. Goods meant for Ireland were sent to Portugal. It was up to the Irish to pick them up there. This route was called the Iberian Trade or the Lisbon run.

Sailing from Ireland, the ships would carry farm products to the United Kingdom. There, they would unload their cargo, get fuel, pick up a British export (often coal), and take it to Portugal. In Portugal, usually Lisbon, Irish ships loaded the waiting American cargo. This might be fertilizer or farm machinery.

Sometimes the cargo wasn't there. It might have been delayed or lost at sea due to the war. In these cases, the Irish captains would load whatever cargo they could find and bring it back to Ireland. This might be wheat or oranges. Sometimes, they even bought their own cargo of coal. The Kerlogue was lucky to have a cargo of coal when two unknown planes attacked her with cannon fire. The shells got stuck in the coal instead of going through her hull. Britain denied being involved. But when the coal was unloaded, shell pieces made in Britain were found. The attackers were Polish planes from the British Royal Air Force.

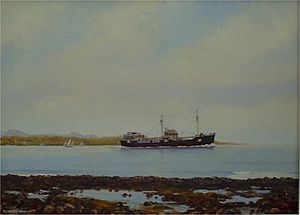

The Cymric was not so lucky. She disappeared in the same waters without a trace.

The Lisbon run was done by small ships called coasters. These ships were not designed for long trips across the deep sea. They were small and sat low in the water. They were meant to stay close to land and quickly get to a harbour if the weather turned bad. The Kerlogue has become a famous example of the Irish merchant navy during the Emergency. Only 335 tons and 142 feet long, the Kerlogue was attacked by both sides and rescued people from both sides. Her rescue of 168 German sailors, given her small size, was amazing.

From January 1941, British authorities required Irish ships to visit a British port. There, they had to get a "navicert." This visit sometimes proved deadly. It also added up to 1,300 miles to the journey. A ship with a "navicert" was allowed to pass freely through Allied patrols and get fuel. However, they would be searched. Irish ships on the "Lisbon run" carried UK exports to Spain and Portugal.

Atlantic Routes

Some British ships traded between Ireland and Britain. Other places were served by Irish and other neutral ships. A British politician, Philip Noel-Baker, told the British parliament that "no United Kingdom or Allied ship has been lost while carrying a full cargo of goods either to or from Eire on an ocean voyage." He added that "a very high proportion of imports from overseas sources into Eire... are already carried in ships on the Eire or on a neutral register." He also said, "The trade between Great Britain and Eire is good for both countries, and the risks to British seamen are small."

During the economic depression, the Limerick Steamship Company sold its two ocean-going ships. They were Ireland's last ships built for long ocean voyages. When the war started, Ireland didn't have a ship designed to cross the Atlantic. British ships were not available. American ships would only travel to Portugal. Ireland relied on other neutral countries. In 1940, several of these ships, from Norway, Greece, Argentina, and Finland, were lost. They were usually carrying wheat to Ireland. Soon, many of these nations were no longer neutral. Ireland had to get its own fleet.

Irish Shipping was formed. The Irish Poplar was Irish Shipping's first ship. It was bought in Spain after its crew had left it. Other ships were bought from Palestine, Panama, Yugoslavia, and Chile. Frank Aiken, an Irish government minister, arranged to rent two oil-burning steamships from the United States. Both were lost to U-boats. The Irish Oak was sunk in a controversial way by a German U-boat. All 33 crew members of the Irish Pine were lost when she was sunk by another U-boat.

Three ships from Estonia were in Irish ports when Estonia was taken over by the Soviet Union. Their crews refused to go back to the new Estonian government. The ships were sold to Irish Shipping. An Italian ship, Caterina Gerolimich, had been stuck in Dublin since the war started. After the fall of Italian Fascism, she was rented, repaired, and renamed Irish Cedar. When the war was over, she returned to Naples with food. This was a gift from Ireland to war-torn Italy.

The Irish Hazel was bought on June 17, 1941. She was 46 years old and needed a lot of repairs. She was "fit for nothing but the scrap yard." A British shipyard won the contract to fix her up. This work was finished in November 1943. Even though the Irish government paid for her purchase and repairs, she was taken by the British and renamed Empire Don. She was returned to Irish Shipping in 1945.

The Irish Shipping fleet brought in a lot of goods across the Atlantic. This included 712,000 tons of wheat, 178,000 tons of coal, 63,000 tons of fertilizer, 24,000 tons of tobacco, 19,000 tons of newsprint, 10,000 tons of timber, and 105,000 tons of other goods. The figures from other shipping companies have not survived.

After the War

When the war ended on May 16, 1945, Éamon de Valera said in his speech to the nation: "To the men of our Mercantile Marine who faced all the dangers of the ocean to bring us essential supplies, the nation is deeply grateful."

The Ringsend area of Dublin has a long history with the sea. When new houses were built there in the 1970s, some streets were named after ships that were lost. These included Breman Road, Breman Grove, Cymric Road, Isolda Road, Pine Road, Leukos Road, Kyleclare Road, and Clonlara Road.

The "Emergency Service Medal" for the "Mercantile Marine Service" was given to everyone who had served six months or longer on an Irish-registered ship during the Emergency.

On September 24, 2001, a monument with the Irish tricolour was put up in England. It remembers the crews lost on neutral Irish ships between 1939 and 1945. This was a "very significant gesture by our British friends" to honor all sailors who died in World War II, no matter their nationality.

In Dublin, a yearly event is held on the third Sunday of November to remember those who died at sea. The Cork event is on the fourth Sunday of November. The Belfast event is on the second Sunday of May.

Images for kids

-

Belfast Commemoration

On the second Sunday every May, an event is held to remember "those who have no grave but the sea," especially in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Ships

| Owner | Boat | Date Lost |

|---|---|---|

| Arklow Schooners | Agnes Craig | |

| Antelope | ||

| Cymric | 24 Feb 1944 | |

| de Wadden | ||

| Gaelic | ||

| Happy Harry | ||

| Harvest King | ||

| Invermore | ||

| J. T. & S. | ||

| James Postlethwaite | ||

| Mary B Mitchell | 20 Dec 1944 | |

| M E Johnson | ||

| Venturer | ||

| Windermere | ||

| City of Cork Steam Packet Company | Ardmore | 11 Nov 1940 |

| Innisfallen | 21 Dec 1940 | |

| Kenmare | ||

| British and Irish Steam Packet Company | Dundalk | |

| Kilkeny | ||

| Meath | 16 Aug 1940 | |

| Munster | 2 Feb 1940 | |

| Wicklow | ||

| Dublin Gas Company | Glenageary | |

| Glencree | ||

| Glencullen | ||

| T Heiton & Co | St Fintan | 22 Mar 1941 |

| St Kenneth | ||

| St Mungo | ||

| Irish Shipping | Irish Alder | |

| Irish Ash | ||

| Irish Beech | ||

| Irish Cedar | ||

| Irish Elm | ||

| Irish Fir | ||

| Irish Hazel | ||

| Irish Larch | ||

| Irish Oak | 15 May 1943 | |

| Irish Pine | 15 Nov 1942 | |

| Irish Plane | ||

| Irish Poplar | ||

| Irish Rose | ||

| Irish Spruce | ||

| Irish Willow | ||

| Limerick Steamship Co | Clonlara | 22 Aug 1941 |

| Kyleclare | 23 Feb 1943 | |

| Lanahrone | ||

| Luimneach | 4 Sep 1940 | |

| Maigue | 4 Jan 1940 | |

| Monaleen | ||

| Moyalla | ||

| Rynanna | 21 Jan 1940 | |

| Palgrave Murphy | Assaroe | |

| City of Antwerp | ||

| City of Bremen | 2 June 1942 | |

| City of Dublin | ||

| City of Limerick | 15 Jul 1940 | |

| City of Waterford | 19 Sep 1941 | |

| W. Herriott, Limerick | Kerry Head | 22 Oct 1940 |

| S. Lockington, Dundalk | Margaret Lockington | |

| R. McGowan & Sons, Tralee | Kerrymore | |

| P. Moloney & Co., Dungarvan | The Lady Belle | |

| L. Ryan, New Ross | Ellie Park | |

| J. Nolan, Skibbereen | Lock Ryan | 7 Mar 1942 |

| J. Creenan, Ballinacurry | Brooklands | |

| J. Rochford, Kilmore Quay | Crest | 17 Sep 1941 |

See also

- The Emergency (Ireland) - internal, national issues in World War II

- Irish neutrality during World War II - international relations

- MV Kerlogue - a famous example of neutral Irish ships in World War II.

- Battle of the Atlantic

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |