Ivaritji facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ivaritji

|

|

|---|---|

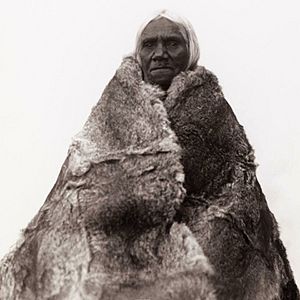

Ivaritji wearing a wallaby-skin cloak, photographed by Norman Tindale in 1928

|

|

| Born | c. 1849 Port Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

|

| Died | 25 December 1929 Point Pearce, South Australia, Australia

|

| Other names | Amelia Taylor, Amelia Savage |

| Occupation | Weaver, cook |

| Known for | Kaurna elder; last native speaker of the Kaurna language |

Ivaritji (born around 1849 – died December 25, 1929) was an important elder of the Kaurna people. The Kaurna are an Aboriginal Australian tribe from the Adelaide Plains in South Australia. She was also known as Amelia Taylor and Amelia Savage. Ivaritji was likely the last person of full Kaurna heritage. She was also the last known speaker of the Kaurna language before it was brought back to life in the 1990s.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Ivaritji's name has been spelled in different ways. Some spellings include Iparrityi, Iveritji, or Everety. In the Kaurna language, "Ivaritji" means "a gentle, misty rain."

Ivaritji's Early Life

Ivaritji was born in Port Adelaide, South Australia, in the late 1840s. Her father was Ityamai-itpina, a leader of the Kaurna people. Her mother was Tankaira from Clare, South Australia. Ivaritji's childhood name was "Itja mau." She had a younger brother named Wima and an older brother named James Phillips. Several other siblings died when they were very young.

Before Europeans arrived in the 1790s, there may have been thousands of Kaurna people. However, new diseases and changes to their way of life greatly harmed them. By the 1850s, only a few Kaurna people remained in the Adelaide area.

Moving to New Areas

As Adelaide grew with European settlers, the Kaurna tribe moved south. They went to the Clarendon district. There, they lived a semi-nomadic life, moving around the southern Adelaide Hills. They often traveled between places where they could get supplies, called ration depots.

Ivaritji's family became well-known in the region. Local white settlers called her parents "King Rodney" and "Queen Charlotte." They called Ivaritji "Princess Amelia."

Life with Adoptive Family

In the early 1860s, both of Ivaritji's parents died. She was then adopted by Thomas Daily and his wife. Thomas Daily was a schoolmaster in Clarendon. He also gave out supplies to Aboriginal people.

Ivaritji lived with them for several years. She learned to read and write in English. After some time, she left to rejoin other Aboriginal people.

Life at Missions

By the late 1800s, Ivaritji and some of the last Kaurna people moved to the Point McLeay Mission. There, Ivaritji worked as a cook for a reverend named George Taplin. For a while, she was married to George Taylor, an Aboriginal man from Kingston.

After working briefly as a house helper in Norwood, she moved again. She went to the Point Pearce Mission Station. She lived there for many years.

Marriage and Later Years

On December 20, 1920, Ivaritji married Charles John Savage. He was a man of African American descent. They married at the Holy Trinity Church in Adelaide.

Charles was not allowed to live at the Point Pearce Mission because he was not Aboriginal. So, the couple moved to Moonta. They lived in a small house on an Aboriginal Reserve called 'the Crossroads'.

The Chief Protector of Aborigines, William Garnet South, did not give them permission to use the 18 acres around their house. Instead, they were only allowed 1 acre. The rest was given to a white farmer. Later, Ivaritji received £1 rent each month from a farmer who grew crops on the land.

She added to Charles's pension and her own supplies by selling mats and baskets. She made these from old baling twine she found in nearby fields. People often saw her in Moonta, selling her handmade items to locals and visitors.

Final Days

In 1929, Ivaritji moved to a shared house on the Point Pearce reserve. She had been finding it hard to support herself. She could not get an age pension because she was considered a "full-blooded" Aboriginal person. This meant she was seen as a ward of the state under the laws at that time.

She became sick with pneumonia and died on Christmas Day 1929. She passed away at the Point Pearce hospital. Ivaritji did not have any children of her own. When she died, some people said she was the "last of her tribe." However, many descendants of her paternal aunt and other Kaurna people were still alive. Their descendants are still alive today.

Ivaritji's Lasting Impact

In her later years, many people interviewed and photographed Ivaritji. These included Daisy Bates, John McConnell Black, Herbert Basedow, and Norman Tindale. She shared many Kaurna words and place-names with them. She also shared details about Kaurna culture and the early history of Adelaide.

Her knowledge was so important that the Anthropological Society of South Australia paid for her to travel. They paid for her trip from Moonta to Adelaide in 1928 so she could be interviewed. Her knowledge was later used to help bring back the Kaurna language in the 1990s.

Whitmore Square in the Adelaide city centre was a popular meeting place for Aboriginal people. This was especially true in the 1930s and 1940s. In 2003, the square was given a second name in her honor: Iparrityi. Plans for a "Hotel Ivaritji" next to the square were approved in 2014. However, the project was stopped in 2021.

There is a special display about Ivaritji at the South Australian Museum. It is in the Australian Aboriginal Cultures gallery.

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |