Norman Tindale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Norman Tindale

|

|

|---|---|

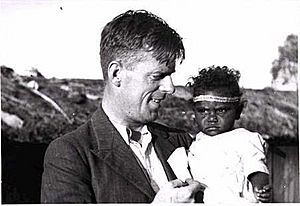

Tindale holding a child from Mona Mona Mission in Queensland, 1938

|

|

| Born |

Norman Barnett Tindale

12 October 1900 Perth, Western Australia, Australia

|

| Died | 19 November 1993 (aged 93) Palo Alto, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of Adelaide |

| Awards |

|

Norman Barnett Tindale (born October 12, 1900 – died November 19, 1993) was an important Australian scientist. He studied many things, including anthropology (the study of human societies and cultures), archaeology (the study of human history through digging up old sites), entomology (the study of insects), and ethnology (the study of cultures and their origins).

Contents

Life and Early Work

Norman Tindale was born in Perth, Western Australia, in 1900. When he was young, his family moved to Tokyo, Japan, where they lived from 1907 to 1915. His father worked there for the Salvation Army. Norman went to the American School in Japan.

In 1917, his family returned to Australia and moved to Adelaide. In 1919, he started working at the South Australian Museum as an entomologist. From a young age, Norman loved taking notes about everything he saw. He would organize these notes before bed, a habit he kept his whole life. This helped him create a huge collection of notes for future generations.

Around this time, Tindale lost sight in one eye because of a gas explosion. This happened while he was helping his father with photographic processing. Even with this injury, he continued his studies. He published many scientific papers on insects, birds, and human cultures before he earned his science degree from the University of Adelaide in 1933.

Exploring Aboriginal Cultures

Tindale's first trip to study human cultures happened in 1921–1922. He mainly wanted to collect insects for the museum. But he also became very interested in the indigenous people he met, from the Cobourg Peninsula to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

He spent six months with a missionary, Hubert E. Warren, exploring areas for a new mission. He then spent nine more months near the Roper River. Tindale wrote detailed reports about the Warnindhilyagwa people on Groote Eylandt, which were the first of their kind.

In 1938–1939, Tindale worked with Joseph Birdsell, another scientist. They traveled across Australia to study Aboriginal reserves and missions. Tindale focused on family histories (genealogies), while Birdsell took measurements. They visited many places, including Cummeragunja Aboriginal reserve in New South Wales.

Tindale collected a vast amount of information, which is now kept at the South Australian Museum. This collection includes family histories, journals, sound and film recordings, drawings, maps, photos, and personal letters. Copies of his work are also held in State Libraries across Australia. This collection is very important for Aboriginal people today, helping them find information about their families and connections to their communities.

Wartime Service

When World War II started, Tindale tried to join the military but was rejected because of his poor eyesight. However, his knowledge of Japanese was very rare in Australia at the time. This made him very valuable for military intelligence.

In 1942, Tindale joined the Royal Australian Air Force. He was given the rank of wing commander and sent to The Pentagon in the United States. There, he worked as an analyst, helping to understand the impact of bombing on Japan.

He also helped set up a unit to examine parts from shot-down Japanese airplanes. By carefully studying the metal pieces and serial numbers, his team could figure out which companies made the parts. This helped them understand Japan's production numbers and what materials they might be running short on.

Tindale also played a big part in stopping Japan's balloon bombing attacks on the United States. His team's detailed analysis of the balloon wreckage helped the U.S. Air Force find and bomb the production factories in Japan.

Later Years and Filmmaking

After working for the South Australian Museum for 49 years, Tindale retired. He then took a teaching job at the University of Colorado at Boulder in the United States. He stayed there until he passed away in 1993, at the age of 93.

From 1926, Tindale was involved in a project to film Aboriginal life. Over 11 years, they created more than 10 hours of film showing different parts of Aboriginal culture, like how they made tools, hunted, gathered food, and cooked. Tindale produced these films.

Important Work and Studies

Tindale is most famous for his work mapping the different groups of Aboriginal Australians at the time Europeans first arrived. He used his own fieldwork and other sources to create his famous Map showing the distribution of the Aboriginal tribes of Australia.

This interest began during a trip to Groote Eylandt. His helper and interpreter, a Ngandi man, showed him how important it was to know the exact boundaries of different tribal lands. This made Tindale question the common belief at the time that Aboriginal people were just nomadic (always moving) and had no strong connection to specific areas. While some of Tindale's methods have changed over time, his main idea that Aboriginal people had strong ties to their land was proven correct.

He also collected many objects for his museum through trade. He was very careful to write down where each object came from.

Entomology

Tindale also specialized in studying a type of moth called the Hepialidae or ghost moth. In the 1920s, he began to improve our understanding of Australian Mantidae (like praying mantises) and mole crickets. Starting in 1932, he wrote many papers over three decades, reorganizing how Australian ghost moths were understood.

Awards and Recognition

Norman Tindale received several important awards for his work. He was given the Verco Medal in 1956 and the Australian Natural History Medallion in 1968. In 1980, he received the John Lewis Medal. He also received honorary doctorates from the University of Colorado in 1967 and the Australian National University in 1980.

In 1993, he was named an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO), a very high honor in Australia. This award was given to his wife after he passed away. Also in 1993, the South Australian Museum named a public gallery in his honor.

Understanding His Legacy

One common discussion about Tindale's maps of Australian tribes is about his idea that a group speaking the same language also had a unified territory. He believed that people who spoke the same language shared a single land identity.

Some have suggested that Tindale's early experience with the Japanese language might have affected how he heard and wrote down words in some Aboriginal languages, like Ngarrindjeri. Japanese is written in syllables, and this might have made him add extra sounds when writing down Aboriginal words.

Tindale's maps have become very well-known. They have been used in legal cases about native title, which are about Aboriginal people's rights to their traditional lands. Sometimes, these maps have caused difficulties for Aboriginal groups trying to prove their connection to certain areas.

For example, Tindale mapped a group called the Djukan people, even though another map of the area didn't show them. He also created a separate entry for a group called the Jadira based on very little information. These kinds of details can make it harder for modern Aboriginal groups to prove their land claims.

Other researchers have also found issues with Tindale's maps in places like Cape York Peninsula and South East Queensland. They suggest he sometimes ignored observations from earlier researchers in favor of information he gathered later from people in places like Palm Island.

Despite these discussions, Tindale's work was very important because he showed that Aboriginal peoples had a strong connection to specific parts of Australia. His maps helped to put a "disappearing people" back on the map, showing their presence across what became colonial Australia. His map was later used as a basis for the maps in the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia.

Books by Norman Tindale

Novels for Children

- The First Walkabout (1954) with Harold Arthur Lindsay

- Rangatira (1959) with Harold Arthur Lindsay

Non-fiction Books

- The Land of Byamee: Australian Wild Life in Legend and Fact (1938)

- Aboriginal Australians (1963) with Harold Arthur Lindsay

- Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names (1974)

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |