Cummeragunja Reserve facts for kids

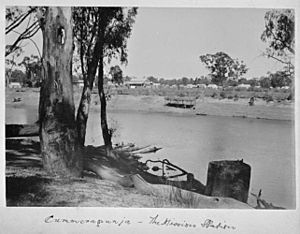

Cummeragunja Reserve, also known as Cummeragunja Station, was an important Aboriginal settlement in New South Wales, Australia. It was located on the Murray River, close to the border with Victoria and near a town called Barmah. People sometimes called it "Cumeroogunga Mission," but it wasn't actually run by missionaries. Most of the people living there were from the Yorta Yorta nation.

The reserve was started between 1882 and 1888. This happened because people living at another place called Maloga Mission were unhappy. They found the rules there too strict under its founder, Daniel Matthews. So, they moved about 5 miles (8 km) upriver to start a new community. The buildings from Maloga were moved and rebuilt at the new site. Their teacher, Thomas Shadrach James, also moved with them.

Cummeragunja became a busy and successful community by the early 1900s. However, over time, the Government of New South Wales took more and more control. It was officially listed as one of four Aboriginal reserves from 1883 to 1964, but the government's control changed a lot during these years. Cummeragunja is famous for a protest in 1939 called the Cummeragunja walk-off. During this event, many residents left the reserve to cross the river into Victoria. They were protesting the very poor living conditions and unfair treatment they faced.

In March 1984, the land was given back to the Yorta Yorta people through the newly formed Yorta Yorta Land Council. Today, many Aboriginal families still live at Cummeragunja.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name of this settlement has been written in different ways over the years. You might see it as Cumeroogunya, Coomeragunja, Cumeroogunga, or Cummerguja. All these names refer to the same important place.

A Look Back: History of Cummeragunja

Official records show that the Cumeroogunya Aboriginal reserve was in an area called the Parish of Bama, in the County of Cadell. It covered a total of 2,600 acres (1,052 hectares). This area was made up of four different reserves. The main one existed from April 9, 1883, to December 24, 1964. Three smaller reserves were added later, starting in 1893, 1899, and 1900.

How Cummeragunja Started

Most of the people who came to live at Cummeragunja Reserve were Yorta Yorta people. They had originally lived at Maloga Mission, which was about 4 miles (6.4 km) away. They decided to leave Maloga because they were tired of the very strict religious rules and the bossy style of its founder, Daniel Matthews.

In April 1881, 42 Yorta Yorta men from Maloga Mission wrote a special letter called a petition. They sent it to the Governor of New South Wales, Augustus Loftus, asking for their own land. Daniel Matthews took this petition to Sydney for them. It was even printed in newspapers like The Sydney Morning Herald and the Daily Telegraph in July 1881, the same day it was given to the governor.

In July 1887, another Governor of New South Wales, Lord Carrington, visited a town called Moama. While he was there, residents from Maloga gave him another petition. This time, they asked Queen Victoria to grant their community land. Important Yorta Yorta leaders like Robert Cooper, Samson Barber, Aaron Atkinson, and William Cooper signed this petition. A newspaper called the Riverine Herald reported on this request. In March 1888, the Minister of Lands agreed to their request. They said that part of the reserve would be divided into smaller areas for individual Aboriginal families to settle on.

A large piece of land, about 1,800 acres (7.3 km²), was bought from the government of the Colony of New South Wales. In 1888, the entire village moved from Maloga to this new site. A superintendent, appointed by the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Association, gave the new place the name Coomerugunja.

Daniel Matthews stopped working with the Aborigines Protection Association in April 1888 when the residents moved. His wife, Janet, said he continued to work for Aboriginal people. They stayed at Maloga Mission, hoping to start a new mission somewhere else, but it didn't happen.

Thomas Shadrach James continued to be the teacher at the new Cummeragunja site. He was known as a very dedicated teacher. He taught his Aboriginal students well, and many of them later became important activists for their people's rights.

In 1889, the "Cumeroogunga Mission Church," which had been moved from Maloga, reopened for worship. At Cummeragunja Station, the community started a farm. Their goal was to become self-sufficient, meaning they could produce everything they needed themselves. In the early years, the residents worked hard to make the land productive. They grew wheat, raised sheep for wool, and produced dairy products.

The NSW Aborigines Protection Association managed the station from the beginning until 1892. The government helped pay for it. But when their money ran out, the management was taken over by the government's own Board for the Protection of Aborigines.

Changes in the 20th Century

In 1907, the individual land blocks that Aboriginal families had were taken away. Later, these blocks were rented out to white farmers.

The Aborigines Protection Act 1909 gave the government even more power over Aboriginal people's lives. In 1915, changes to this Act gave the Board for the Protection of Aborigines even wider powers. The Board took much greater control of Cummeragunja and its residents. People living on the reserve faced very strict and limiting rules. The managers of the Reserve could even force residents to leave if they were accused of "misconduct." They were told to go earn a living somewhere else. All the money earned from the farm went to the Board. The Board then gave out small, often unhealthy, amounts of food and supplies to the workers instead of fair wages. The 1915 changes also gave the Board the power to remove children from their families. This happened often. Girls were often sent to work in homes as servants or to places like the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls to be trained for these jobs.

The Board kept all the money earned by the Station, and the community was neglected. Poor sanitation, bad housing, and a lack of clean water led to illnesses like tuberculosis and whooping cough. These diseases especially affected the elderly and young children, leading to many deaths. By the 1930s, conditions had become much worse. Residents were often not allowed to leave the station, and many of their relatives were forced to move away. There wasn't enough food or supplies, and people had to share blankets and live in simple huts made of rags. The station manager, Arthur McQuiggan, was known for bullying and punishing residents if they complained.

In May 1938, two anthropologists, Joseph Birdsell and Norman Tindale, visited Cummeragunja. The teacher at the time, Thomas Austin, thought he knew a lot about Aboriginal people and had shared his ideas with another anthropologist, A.P. Elkin. Even though the community members couldn't stop the study, they were aware of their rights and spoke about their problems. Tindale and Birdsell listened to them. Years later, Tindale used some of the issues at Cummeragunja to support his idea that while Aboriginal people of mixed heritage could be successfully integrated into white society, the reserve system was not working. He mentioned the problems at Cummeragunja in his report. One good thing came from the scientists' visit: they created a collection of photographs and stories that are very important to the descendants of Cummeragunja residents today.

The 1939 Cummeragunja Walk-off

Conditions at Cummeragunja became so bad that residents decided to take a stand. They sent a telegram to a former resident and activist named Jack Patten. When he tried to speak to them, he was arrested. This made things even worse. On February 6, 1939, about 170 residents walked off the mission in protest against their unfair treatment. They crossed the river into Victoria and set up camps along the riverbanks. Margaret Tucker and Geraldine Briggs were two of the most well-known protesters during this event.

This protest became famous as the Cummeragunja walk-off. It was the first large-scale strike by Indigenous people in Australia. It later inspired many other movements and protests for Aboriginal rights.

Many of the people who took part in the walk-off settled in northern Victoria. They found new homes in towns like Barmah, Echuca, Mooroopna, and Shepparton.

Land Taken After World War II

After World War II, the government gave parts of the land at Cummeragunja and other Aboriginal reserves to white Australian soldiers who had returned from the war. This was part of a plan called the Soldier Settlement Scheme. However, Indigenous soldiers who had also fought in the war were not allowed to be part of this scheme. So, even those from Cummeragunja who had served their country were not given land in this way.

1953: The Station Closes

In 1953, Cummeragunja was no longer officially a "station." Its status was changed to just an Aboriginal reserve. Only a few residents remained, but they kept fighting for their right to start farming the land again. A company called Cummeragunga Pty Ltd was officially registered in 1965.

In 1956, before Queen Elizabeth II visited for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, the remaining families at Cummeragunja were moved. They went to 10 specially built houses in an area known as Rumbalara. The Rumbalara Aboriginal Co-operative was started in 1980. It now provides health services for the community. There is also a Rumbalara Football Netball Club.

1984: The Land is Returned

On March 9, 1984, the ownership of the Cummeragunja land was officially given back to the newly formed Yorta Yorta Local Aboriginal Land Council. This was a very important moment for the community.

Who Manages Cummeragunja Now?

Many Aboriginal families continue to live at Cummeragunja today. As of 2020, Cummeragunja is owned and managed by the Cummeragunja Local Aboriginal Land Council. This local council is part of a larger organization called the NSW Aboriginal Land Council.

Important People from Cummeragunja

Many inspiring people have come from Cummeragunja. Here are a few:

- Jack Charles, a famous actor and co-founder of Australia's first Indigenous theatre group, Nindethana.

- William Cooper, who started the Australian Aborigines' League to fight for Aboriginal rights.

- Jimmy Little, a well-loved musician, singer, songwriter, and guitarist.

- Sir Douglas Nicholls, a leading Australian rules football player, a pastor, and later the Governor of South Australia.

- Shadrach James, a talented footballer who played for Fitzroy and other country teams.

- Bill Onus, a political activist, businessman, and performer.

- Jack Patten, who founded the Aborigines Progressive Association and helped organize the 1938 Day of Mourning protest in New South Wales.

- The Sapphires, a famous singing group whose story inspired the international film The Sapphires (film) and an Australian play.

- Margaret Tucker, who helped start the Australian Aborigines League. She also wrote a book called If Everyone Cared (1977), which was one of the first books to share the experiences of the Stolen Generations.

- Margaret Wirrpanda, Margaret Tucker's niece, who is also an activist.

See also

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |