Jo Baer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jo Baer

|

|

|---|---|

Baer in 2014

|

|

| Born |

Josephine Gail Kleinberg

August 7, 1929 Seattle, Washington, U.S.

|

| Died | January 21, 2025 (aged 95) Amsterdam, Netherlands

|

| Movement | Minimalism |

| Awards | Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award (2004) Jeanne Oosting Award (2016) |

Josephine Gail Baer (born Kleinberg; August 7, 1929 – January 21, 2025) was an American painter. She is known for her connection to minimalist art. She started showing her paintings in the mid-1960s. Later, in the mid-1970s, she changed her style. Baer began to mix images, symbols, words, and phrases in a new way. She called this "radical figuration." She lived and worked in Amsterdam, Netherlands, until her death.

Contents

Jo Baer's Early Life and Art (1929–1960)

Josephine Gail Kleinberg was born in Seattle, Washington, on August 7, 1929. Her mother, Hortense, was an artist and believed strongly in women's rights. This influenced Jo's ideas about being independent. Her father, Lester, was a successful broker who traded hay and grain.

Jo studied art as a child at the Cornish College of the Arts. Her mother wanted her to draw for medical books. So, Jo studied biology at the University of Washington from 1946 to 1949. She left college early to marry Gerard L. Hanauer.

After her first marriage ended, Baer went to Israel in 1950. She spent a few months exploring rural communities called kibbutzim. When she returned to New York City, she studied psychology at The New School for Social Research from 1950 to 1953. She worked during the day and went to school at night.

In 1953, Baer moved to Los Angeles. She soon married Richard Baer, a television writer. Their son, Joshua Baer, was born in 1955. Joshua later became an art dealer. Jo and Richard divorced in the late 1950s. During this time, Baer started painting and drawing again. She became friends with artists like Edward Kienholz. She also met painter John Wesley, whom she married in 1960.

In 1960, Jo, John, and Joshua moved to New York. Jo lived there until 1975. After separating from Wesley, she was in a long relationship with sculptor Robert Lawrance Lobe. Baer's early work was inspired by artists like Mark Rothko and Jasper Johns. Rothko's art helped her think about how to use a painting's shape. Johns's work showed her that a painting could be "the thing itself."

Jo Baer's Art Career (1960–1975)

Paintings and Exhibitions

In 1960, Baer moved away from Abstract Expressionism. She started making simple, hard-edge paintings that did not show real objects. Two important early works in this style are Untitled (Black Star) (1960–1961) and Untitled (White Star) (1960–1961). Both are now at the Kröller-Müller Museum.

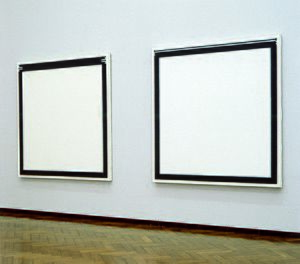

Later, she made her paintings even simpler. The middle part of the canvas became completely white. In 1962, Baer began her Korean series, which included sixteen paintings. An art dealer named Richard Bellamy gave them this name. He said Baer's paintings were as unknown as Korean art was to most Westerners.

The Koreans paintings had a large white area. This white was surrounded by bands of sky blue and black. These bands seemed to shimmer and move. This optical effect showed Baer's interest in "the idea of light." Baer said she was inspired by Samuel Beckett's book The Unnamable. She was reading it at the time. His ideas about how things pass through boundaries made her think about the edges between spaces.

From 1964 to 1966, many of Baer's works had two colored bands around the edges of the canvas. The outer band was thick and black. Inside it, a thinner band was painted in another color, like red or blue. In 1971, Baer explained her art. She wrote that non-objective painting uses "edges and boundaries, contours and gradients, brightness, darkness and color reflections."

Baer became a respected artist in the growing Minimalist movement. Other artists like Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd accepted her. In 1964, artist Dan Flavin organized an important show called "Eleven Artists." It helped define the main figures of Minimalism. Baer was included in this show.

In 1966, Baer had her first solo exhibition at the Fischbach Gallery. This gallery was a key place for new art. That same year, her work was shown in "Systemic Painting" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. She also took part in "10," a group show at the Virginia Dwan Gallery. These exhibitions helped establish her reputation in the New York art world.

In the late 1960s, Baer experimented with color. She also changed where the viewer's eye focused in her art. For her series The Stations of the Spectrum (1967–1969), she painted the white surfaces gray. She then made them into three-part paintings (triptychs). She felt they had more impact when hung together.

Next, she wanted to see "what happens around a corner." This led to her Wraparound paintings. In these, Baer painted thick black bands with colored edges (blue, green, orange) that went around the sides of the canvas. Artists usually ignore these areas. The action was now at the edges. Baer wrote, "Sensation is the edge of things."

She also added diagonal and curved lines of color across her white paintings and down their sides. These paintings had unusual titles like H. Arcuata (1971) and V. Lurida (1971). These titles came from a book of botanical Latin she owned. "H." meant "horizontal" and "V." meant "vertical." "Arcuata" means curved, and "lurida" means "pale" or "shining."

Writings About Art

Baer was also an active writer in New York. She wrote letters, articles, and statements in art magazines. She defended painting, saying it was still important. Some Minimalist sculptors argued that painting was no longer relevant. Because she challenged these powerful artists, some former friends avoided her.

One of Baer's most important essays was "Art & Vision: Mach Bands," published in 1970. She used her science background to discuss how we see things. She wrote about Mach bands, which are an optical illusion. This illusion makes light areas seem lighter and dark areas seem darker when different colors are next to each other. She connected this idea to how we experience edges and boundaries in modern art.

Jo Baer's Later Career (1975–2025)

In 1975, the Whitney Museum of American Art held a show of Baer's Minimalist work. However, Baer felt she had reached a dead end with her non-objective painting. She felt her style had become too predictable. Two paintings, M. Refractarius (1974–75) and The Old Year (1974–75), show her desire to move away from Minimalism.

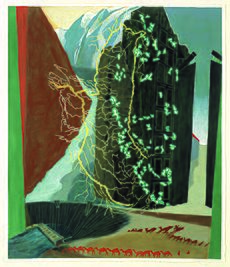

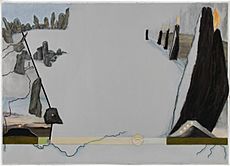

Baer needed a change from the New York art world. In June 1975, she moved to Smarmore Castle in County Louth, Ireland. It was a manor and working farm. In this new place, she was inspired by horses, birds, and country life. She began to paint in a more figurative way. She layered fragments of animals, human bodies, and objects. She used soft, see-through colors. Baer also used images from ancient cave paintings and sculptures.

In 1977, Baer had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford. There, she met British artist Bruce Robbins. They lived and worked together from 1978 to 1984. They created paintings, drawings, and writings. Their joint works were shown in eight exhibitions. While in London, Baer wrote a famous article called "I am no longer an abstract artist." It was published in Art in America in October 1983.

In the article, Baer said that abstract art had lost its meaning. She argued that modern art needed "metaphor, symbolism, and hierarchical relationships." She announced that she and Robbins were working on "radical figuration." This new style would use these ideas.

In 1984, Baer moved to Amsterdam by herself. She lived there until her death. In the 1990s, Baer's paintings became "more declarative." They had richer colors and stronger light-dark contrasts. They also offered more cultural and social criticism. She combined images and symbols from different cultures. She also used quotes from books and ideas about war, nature, greed, and death. Examples include Shrine of the Piggies (2000) and Testament of the Powers That Be (2001).

Baer also painted about her own life. These works include Altar of the Egos (Through a Glass Darkly) (2004) and Memorial for an Art World Body (Nevermore) (2009). A series of six works called In the Land of the Giants (2011) was shown at the Stedelijk Museum in 2013.

Baer's writings were collected in a book called Broadsides & Belles Lettres: Selected Writings and Interviews 1965–2010. This book shares her thoughts on art and her own work.

Many museums have shown Baer's work over the years. These include the Kröller-Müller Museum, the Stedelijk Museum, and the Dia Center for the Arts. In 2013, two solo shows ran at the same time: "In the Land of the Giants" in Amsterdam and "Jo Baer. Gemälde und Zeichnungen seit 1960" in Cologne. Her work was also part of the 2017 Whitney Biennial.

Jo Baer passed away in Amsterdam on January 21, 2025, at the age of 95. She had bladder cancer. She is survived by her son, Josh.

Collections

Baer's works are held in many public collections around the world, including:

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, US

- Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, US

- Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, US

- Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, Texas, US

- Guggenheim Museum, New York City, New York

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, US

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City, New York, US

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., US

- Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

- Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, US

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California, US

- Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Tate Gallery, London, UK

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, New York, US

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, US