John Chamberlain (letter writer) facts for kids

John Chamberlain (born 1553, died 1628) was a famous English letter writer. He wrote many letters between 1597 and 1626. These letters are very important for understanding history and are also well-written.

A historian named Wallace Notestein said that Chamberlain's letters are the first large collection of English letters that are easy for people today to read. They are a key source for anyone studying that time period.

Contents

Life of John Chamberlain

John Chamberlain's father, Richard, was a successful businessman who sold iron goods. He was also the Sheriff of London and led the Ironmongers' Company twice. Richard left John enough money so he never had to work for a living. His mother, Anne, also came from a family of iron merchants.

Even though John Chamberlain didn't want a big career for himself, he used his connections to help his friend, Dudley Carleton. Carleton started in a small job in diplomacy and became a top government official, the Secretary of State, shortly after Chamberlain died. Carleton saved all the letters they sent to each other. Most of Chamberlain's letters that we have today are from this collection. Chamberlain also wrote to Sir Ralph Winwood, who was an ambassador in the Netherlands for many years. He probably wrote to many other friends too.

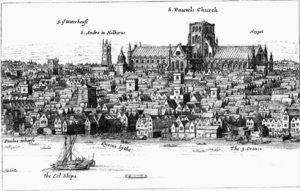

Chamberlain wrote at least one long letter every week. His goal was more than just being friendly. He wanted to give his friends, who were living in other countries, useful and true information about what was happening in London. Chamberlain would walk to St Paul's Cathedral every day. There, he would gather the latest news and then report it to his friends. He tried to be as accurate and fair as possible. He even included what people thought about the news.

Chamberlain's letters are especially helpful for understanding what people thought about King James I. They also give details about the royal family, the court, and England's early trading activities around the world.

Chamberlain is valued not only for the news he shared but also for his writing. Historian A. L. Rowse called him "the best letter writer of his time." Chamberlain was careful to observe things without adding too much of his own opinion. He entertained his friends by mixing facts with humor and interesting details. He also included lighter stories to keep his readers interested. Scholar Maurice Lee, Jr., said that the letters between John Chamberlain and Dudley Carleton are "the most interesting private correspondence of Jacobean England."

Chamberlain's Personality

Chamberlain's letters show us what a typical London gentleman was like during the late Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. He was fair in his political and religious views. His letters show him as a kind and thoughtful friend. He preferred a peaceful life and watched the world around him as an observer.

Even though he helped his friends find jobs, he wasn't interested in power or money for himself. He lived a quiet life as a bachelor. He once wrote: "I am past all ambition, and wish nor seek nothing but how to live suaviter and in plenty" (which means "pleasantly and in comfort"). This calm approach made his letters very fair and objective. He worked hard to get his facts right. He could see through false appearances but was never mean or angry. His kindness as a person is clear in the fair way he wrote his letters. Just as his friends trusted him with important secrets, historians trust his information and understanding of that time. Historian Alan Stewart called Chamberlain "a notable barometer of public opinion."

Chamberlain knew he had some faults, but they didn't affect his letters. He was naturally curious and enjoyed gossip, which actually helped him as a letter writer. He had been a sickly child. Even though he went to Cambridge University and a law school called the Inns of Court, he never finished his degree or became a lawyer. He always lived with friends or relatives. The one time he tried to live on his own, it was too much for him.

In his will, he left generous gifts to many friends and family members. He asked to be buried simply, "with as little trouble and charge as may be answerable to the still and quiet course I have always thought to follow in my life-time."

Chamberlain's Friends

Chamberlain had an interesting group of friends. Most of them were from the middle class, either from business backgrounds or from less wealthy country families. These included Ralph Winwood and Dudley Carleton, both of whom became top government officials. These men saw themselves as professional public servants rather than people who just spent time at court.

Winwood, like Carleton, started as a diplomat. Chamberlain's letters often talked about Winwood's chances of becoming Secretary of State, a job he finally got in March 1614. Chamberlain remained close friends with Winwood and often stayed at his country home. The information Chamberlain shared in his letters often came from this friendship.

Other important friends of Chamberlain included Henry Wotton, who was also a significant letter writer; Thomas Bodley, who started the famous Bodleian Library in Oxford; the religious scholar Lancelot Andrewes; and the historian William Camden. Chamberlain was always a welcome guest at people's homes. In the summer, he would leave London, which he called "this misty and unsavoury town." He would go on what he called his happy "progresses," staying at different country houses. For a while, Chamberlain lived with the scientist and doctor William Gilbert. He might have met Gilbert at Cambridge University.

Having such a wide network of friends and contacts allowed Chamberlain to report on the main events of the day and understand the general mood. Using these personal sources, as well as his contacts at St Paul's, Chamberlain gave his friends information about important people in England. These included Walter Raleigh; the government official Robert Cecil; the philosopher Francis Bacon; and the king's favorite, Robert Carr, and his wife Frances. Chamberlain knew many people, and if he didn't know someone, his friends could tell him about them.

Chamberlain's letters also shed light on major events during his adult life. These included the rebellion led by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex; King James becoming king; the Gunpowder Plot; the Thomas Overbury case; the rise of King James's last favorite, George Villiers; and the Spanish Match (a plan for the future King Charles to marry a Spanish princess). Chamberlain also wrote about leading artists and writers of his time. These included the poet John Donne, the architect Inigo Jones, and the playwright Ben Jonson. However, if he knew William Shakespeare, he never mentioned him. Chamberlain didn't seem to go to the theater much. In 1614, he wrote about the new Globe Theatre: "I hear much speech of this new playhouse, which is said to be the fairest that ever was in England, so that if I live but seven years longer I may chance make a journey to see it."

Dudley Carleton, Chamberlain's Main Friend

Chamberlain's most important friend and letter receiver was Dudley Carleton. Carleton was about twenty years younger than Chamberlain. When they started writing to each other in the 1570s, Carleton was a young man looking for a career. Chamberlain, through his friendship with Winwood, helped Carleton get his first job at the English embassy in Paris. By the time Chamberlain died, Carleton was a high-ranking diplomat, almost ready to become Secretary of State.

Carleton was very good at keeping his papers. Because of him, we have a huge collection of their letters, which is a key source for that time. Sometimes, Carleton even shared secret diplomatic information with Chamberlain, knowing his friend could be trusted.

Chamberlain not only wrote letters to Carleton but also ran errands for him. These errands sometimes brought him into contact with important political figures. After the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, Carleton was briefly held because he had been a secretary to one of the plotters. He couldn't find work. Chamberlain worked hard to help Carleton get back into favor. For example, he visited Sir Walter Cope, a friend of Cecil's. Carleton eventually found work abroad. Chamberlain also paid Carleton's bills, delivered gifts, and passed messages to his political contacts. Carleton often asked Chamberlain for advice on both political and personal matters. Chamberlain's usual advice was patience. Carleton always valued Chamberlain's friendship and support.

Gathering News

Chamberlain was especially helpful to Carleton as a source of news from London. Chamberlain's main goal in his letters was to share news from the capital with his friends, who were often living abroad. Sir Dudley Carleton, for example, spent most of his career in Venice or the Hague. Chamberlain was the perfect source for Carleton and others because he loved to hear the latest news.

Every day, he walked to St Paul's Cathedral to hear the latest gossip and news from the "news-mongers." At that time, the hallways and main area of the cathedral, known as Paul's walk, were a meeting place for people who wanted to stay updated on current events. Chamberlain was skilled at getting news about politics, wars, court matters, and trials from people there. Besides those who walked St Paul's for news, the cathedral and its surroundings were full of beggars, sellers, and people selling pamphlets and books. Even though his letters had a serious purpose, Chamberlain made them lighter with news of more fun events. For example, he wrote about a long-distance race between two royal runners and a man and his horse on the roof of St Paul's!

King James and the Court

Even though Chamberlain knew people in high society, he was never close to the royal court, and he didn't want to be. Chamberlain's letters give good reports on the biggest scandal of King James's reign. This was the divorce and later murder conviction of Frances Howard, Countess of Essex. Even before she divorced the Earl of Essex to marry Robert Carr, the king's favorite, Chamberlain reported that the countess had sought help to get rid of her husband.

On October 14, 1613, he noted both the Essexes' divorce and the death of Robert Carr's friend Thomas Overbury in the Tower of London. He wrote that Overbury's body looked suspicious, suggesting he might have died from something bad. Frances Howard married Robert Carr soon after her divorce, with the king's approval. They became the Duke and Duchess of Somerset. However, in 1615, it was discovered that Overbury had been poisoned. In 1616, the couple were found guilty of planning his murder and were locked in the Tower. Historians often use Chamberlain's letters as a source for these events. He wrote with a tone of shame and disgust at the court, but he reported the facts fairly, without celebrating the Somersets' downfall.

In a time when spies were everywhere and letters weren't always safe, Chamberlain was careful in what he said about King James. James was the Scottish king who became King of England after Elizabeth I died in 1603. However, it's clear from Chamberlain's letters that he wasn't very impressed by James. He wrote, "He forgets not business, but he hath found the art of frustrating men's expectations and holding them in suspense." Chamberlain gives us more insights into James's personality than any other source from that time. His letters show how people of his social class viewed the king and the court.

Despite Chamberlain's disapproval of James, he never described him as clumsy or rude, as some later historians did. He also never suggested that James's closeness with his male favorites was romantic, perhaps to be safe. Instead, he reported James's self-centeredness, bossiness, and poor judgment. For example, he tells us that during a sermon, James started interrupting so loudly that the Bishop couldn't continue. When courtiers told James it wasn't the custom to have a play on Christmas night, he replied: "I will make it a fashion." Chamberlain also noted how James liked to get personally involved in scandals and court cases. He was always throwing people in the tower for speaking out of turn. Chamberlain also provides valuable details about the king's habits. For instance, he reported that even when ill, James still loved country sports. He was so eager to see hawks fly that he wouldn't be stopped. If he couldn't hunt, he would have his deer "brought to make a muster before him."

Chamberlain thought James spent too much money and was not a good judge of people. He especially disliked James giving away royal money and lands to his favorites when he often couldn't pay government officials. Chamberlain didn't seem to admire any of the Howard family who gained power after Robert Cecil died in 1612. He also didn't like James's favorites, Robert Carr, Duke of Somerset, and George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham.

Chamberlain's Writing Style

Chamberlain's writing style is serious and objective. He had a keen eye for exact details. His style mixes public and private information, serious and unimportant topics, all reported carefully and precisely. He added his own quick remarks. He explained and commented on his information, laying it out clearly and logically. He also shared his own thoughts on how valuable the information and opinions he reported were. His sentences were clearly written with care. Chamberlain's letters show he was an educated and cultured man. He could quote French, Italian, and Spanish, and he knew old English and classical literature. Sometimes his humor was a bit predictable, and he even sent the same letter to different friends. His figures of speech were common sayings, often using images from hunting, falconry, horse riding, farming, and sailing. Chamberlain's writing style stayed the same throughout the many years he wrote letters.

Later Years and Death

Chamberlain's letters show how the country's mood changed in his later years. After Queen Elizabeth died, Chamberlain felt confident because Elizabeth's chief minister, Robert Cecil, stayed in office. He called Cecil "the great little lord." After Cecil's death in 1612, Chamberlain's view of the world became a bit sadder, and he missed the "good old days." This reflected a change in public opinion that historians have also noticed.

Even when he was very old, Chamberlain kept writing letters. Many of his friends had died, and sometimes he felt like giving up. Once, when he forgot to tell Carleton some news, he said, "Whether it be that continual bad tidings hath taken away my taste, or that infirmity of age grows fast upon me, and makes me not regard how the world goes, seeing I am like to have so little part in it, for about the middle of the month I began to be septuagenarius" (meaning he was turning seventy). In his later days, Chamberlain didn't like to travel as much. He also had problems with lawsuits after his brother Richard died, leaving him as the main heir. He wrote: "Now am I left alone of all my father's children... the last of eight brothers and sisters, and left to a troubled estate, not knowing how to wrestle with suits and law business and such tempestuous courses after so much tranquillity as I have hitherto lived in."

However, Chamberlain was quite healthy in his old age. He managed to avoid London's epidemics and the plague, though the cold bothered him more and more. We don't have any letters from Chamberlain to Carleton after Carleton returned to England in 1626.

Chamberlain signed his will on June 18, 1627, nine months before he died. He left gifts to charities, to poor prisoners, and to the patients of Bedlam (a famous hospital). He also left gifts to many family members and friends.

See also

|

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |