John Forbes Nash Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Forbes Nash Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

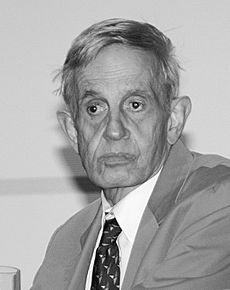

Nash in the 2000s

|

|

| Born | June 13, 1928 Bluefield, West Virginia, U.S.

|

| Died | May 23, 2015 (aged 86) |

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Non-Cooperative Games (1950) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert W. Tucker |

John Forbes Nash, Jr. (born June 13, 1928 – died May 23, 2015) was a brilliant American mathematician. He made very important discoveries in areas like game theory, geometry, and equations. Game theory helps us understand how people or groups make decisions when their choices affect each other.

Nash, along with two other game theorists, won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994. Later, in 2015, he also received the Abel Prize, which is like the Nobel Prize for mathematics.

While studying at Princeton University, Nash came up with ideas like the Nash equilibrium. This idea is now a key part of game theory and is used in many different fields. He also solved complex math problems related to geometry.

Sadly, in 1959, Nash started to show signs of a mental illness called schizophrenia. He spent several years getting treatment in hospitals. After 1970, he slowly got better and was able to return to his math work. His life story, including his struggles and recovery, was told in the book A Beautiful Mind and a movie with the same name. In the movie, Russell Crowe played John Nash.

Contents

Early Life and School

John Forbes Nash Jr. was born on June 13, 1928, in Bluefield, West Virginia. His father, John Forbes Nash Sr., was an electrical engineer. His mother, Margaret Virginia Nash, used to be a schoolteacher. John also had a younger sister named Martha.

John learned a lot from books at home. His parents helped him take advanced math classes while he was still in high school. He went to Carnegie Institute of Technology on a scholarship. He first studied chemical engineering, then chemistry, and finally switched to mathematics.

After earning his bachelor's and master's degrees in math in 1948, Nash received a special fellowship. This allowed him to continue his studies at Princeton University. His former teacher, Richard Duffin, wrote a letter saying Nash was a "mathematical genius." Nash chose Princeton because it was closer to his family and they seemed to value him more. At Princeton, he began developing his famous equilibrium theory.

Amazing Math Discoveries

John Nash didn't publish a huge number of papers, but the ones he did write were very important. As a student at Princeton, he made big contributions to game theory. Later, at MIT, he focused on differential geometry, which is a type of math that studies shapes and spaces.

In 2011, the National Security Agency (NSA) released some letters Nash wrote in the 1950s. In these letters, he suggested a new kind of machine for encryption and decryption. This showed that Nash had ideas about modern cryptography long before they became common.

Understanding Game Theory

Nash earned his PhD in 1950 with a short paper about "non-cooperative games." This paper introduced the idea of the Nash equilibrium. This is a situation in a game where no player can do better by changing their strategy, as long as the other players don't change theirs. It's a key idea in understanding how people make choices in competitive situations.

In the early 1950s, Nash continued to research game theory. His work helped him win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1994.

Geometry and Equations

While at MIT, Nash looked for big math problems to solve. He worked on a problem about how curved spaces can be "embedded" or placed perfectly inside a flat space. His solutions are known as the Nash embedding theorems. One of these theorems is considered one of the most important math achievements of the 20th century.

Nash's work on these problems involved solving very complex partial differential equations. These are special types of equations used to describe how things change in space and time. His methods were very new and creative.

His Struggle with Mental Illness

In 1959, Nash began to show signs of mental illness. His wife said his behavior became very strange. He started to believe that people wearing red ties were part of a secret plot against him. He even sent letters to embassies, saying they were trying to form a new government.

His mental health issues affected his work. During a lecture at Columbia University, he tried to present a complex math proof, but his talk was hard to understand. His colleagues quickly realized something was wrong.

In April 1959, Nash was admitted to McLean Hospital. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a mental illness that can cause people to have strange thoughts and see or hear things that aren't there. Over the next nine years, he spent time in different psychiatric hospitals. He received various treatments, including medications.

Nash later said that he only took medicine when he felt forced to. He also mentioned that the movie A Beautiful Mind incorrectly showed him taking certain medications. He believed this was done to encourage people with mental illness to take their prescribed medicine.

After 1970, Nash stopped taking medication and was never hospitalized again. He slowly got better. His former wife, Alicia, helped him by providing a stable home and support. He was able to return to the Princeton mathematics department. His recovery was helped by living a "quiet life" with people who supported him.

Nash said his "mental disturbances" started when his wife was pregnant in 1959. He described how his thinking changed from being logical to having delusions. He felt like a special messenger and believed there were hidden schemers against him. He thought his unusual way of thinking might have helped him have good scientific ideas.

He started hearing voices in 1964 but learned to ignore them. After spending a long time in hospitals, he started to reject his strange ideas. This allowed him to work on math again for a while. By the late 1960s, he had a relapse. Eventually, he decided that his "politically oriented" strange thoughts were a waste of time. In 1995, he said that his mental illness prevented him from reaching his full potential for almost 30 years.

Awards and Later Career

In 1978, Nash received the John von Neumann Theory Prize for his work on game theory. He also won the Leroy P. Steele Prize in 1999.

In 1994, he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his groundbreaking work on game theory. In the late 1980s, Nash started using email to connect with other mathematicians. They realized he was the famous John Nash and that his new work was valuable. This group helped convince the Nobel committee that Nash was well enough to receive the award.

Nash continued to work on advanced game theory. Between 1945 and 1996, he published 23 scientific studies. He also shared his ideas about mental illness, suggesting that sometimes unusual behaviors might have hidden benefits.

He also thought about the role of money in society. He believed in creating a more stable "ideal money" that people could trust, rather than money that could easily lose its value.

Nash received many honorary degrees from universities around the world. He was also a popular guest speaker at various events. In 2006, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

Just a few days before his death, on May 19, 2015, Nash and Louis Nirenberg were given the 2015 Abel Prize. They received it from King Harald V of Norway for their important work on partial differential equations.

Personal Life

In 1951, Nash started working at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He later met Eleanor Stier, a nurse, and they had a son named John David Stier.

After this, Nash met Alicia Lardé Lopez-Harrison, who had studied physics at MIT. They got married in February 1957. In 1958, Nash got a permanent job at MIT, but soon after, his mental illness began to show. He left his job at MIT in 1959. His second son, John Charles Martin Nash, was born a few months later.

Because of the stress of dealing with his illness, Nash and Alicia divorced in 1963. However, after he left the hospital for the last time in 1970, Nash moved back into Alicia's house as a boarder. This stable environment seemed to help him, and he learned to control his strange thoughts. Princeton University allowed him to attend classes. He kept working on math and was eventually allowed to teach again. In 2001, Alicia and Nash remarried. Their son, John Charles Martin Nash, also earned a PhD in mathematics and was later diagnosed with schizophrenia.

His Death

On May 23, 2015, John Nash and his wife, Alicia, died in a car accident. They were on the New Jersey Turnpike after returning from Norway, where Nash had received the Abel Prize. They had planned to be picked up by a limo, but their flight changed, so they took a taxi instead.

Their taxi driver lost control of the car and hit a guardrail. Both Nash and his wife were thrown from the car. Police said it looked like neither of them was wearing a seatbelt. John Nash was 86 years old when he died. He was survived by his two sons, John Charles Martin Nash and John David Stier.

After his death, many newspapers and scientific groups around the world wrote about his life and achievements.

His Legacy

In the 1970s, at Princeton, Nash was sometimes called "The Phantom of Fine Hall." This was because he would often be seen scribbling complex equations on blackboards late at night.

His life story became very famous with Sylvia Nasar's book A Beautiful Mind, published in 1998. The book was then made into a movie in 2001, directed by Ron Howard. Russell Crowe played Nash in the film. The movie won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Crowe also won several awards for his amazing performance as Nash.

Awards

- 1978 – INFORMS John von Neumann Theory Prize (with Carlton Lemke) for their important work in game theory.

- 1994 – Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (with John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten) for their new ideas about how players reach a balance in non-cooperative games.

- 1999 – Leroy P. Steele Prize for Seminal Contribution to Research for his 1956 paper on embedding Riemannian manifolds.

- 2015 – Abel Prize (with Louis Nirenberg) for their major contributions to the theory of nonlinear partial differential equations.

Documentaries and Interviews

- 60 Minutes: "John Nash's Beautiful Mind" (March 17, 2002)

- American Experience: "A Brilliant Madness" (April 28, 2002)

- Interview with Marika Griehsel for Nobel Prize Outreach (September 1–4, 2004)

- One on One with Riz Khan on Al Jazeera English (December 5, 2009)

- "Interview with Abel Laureate John F. Nash Jr." in Newsletter of the European Mathematical Society (September 2015)

Publication List

- Nash, John F., Jr. (1945). "Sag and tension calculations for cable and wire spans using catenary formulas." Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

- Nash, John F., Jr. (1950a). "The bargaining problem." Econometrica.

- Nash, John F., Jr. (1950b). "Equilibrium points in n-person games." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- Nash, J. F., & Shapley, L. S. (1950). "A simple three-person poker game." Contributions to the Theory of Games, Volume I.

- Nash, John (1951). "Non-cooperative games." Annals of Mathematics.

- Nash, John (1952a). "Algebraic approximations of manifolds." Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians.

- Nash, John (1952b). "Real algebraic manifolds." Annals of Mathematics.

- Nash, John (1953). "Two-person cooperative games." Econometrica.

- Mayberry, J. P., Nash, J. F., & Shubik, M. (1953). "A comparison of treatments of a duopoly situation." Econometrica.

- Nash, John (1954). "C1 isometric imbeddings." Annals of Mathematics.

- Kalisch, G. K., Milnor, J. W., Nash, J. F., & Nering, E. D. (1954). "Some experimental n-person games." Decision Processes.

- Nash, John (1955). "A path space and the Stiefel–Whitney classes." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- Nash, John (1956). "The imbedding problem for Riemannian manifolds." Annals of Mathematics.

- Nash, John (1957). "Parabolic equations." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

- Nash, J. (1958). "Continuity of solutions of parabolic and elliptic equations." American Journal of Mathematics.

- Nash, John (1962). "Le problème de Cauchy pour les équations différentielles d'un fluide général." Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France.

- Nash, J. (1966). "Analyticity of the solutions of implicit function problems with analytic data." Annals of Mathematics.

- Nash, John F., Jr. (1995). "Arc structure of singularities." Duke Mathematical Journal.

- Nash, John (2002a). "Ideal money." Southern Economic Journal.

- Nash, John F., Jr. (2008). "The agencies method for modeling coalitions and cooperation in games." International Game Theory Review.

- Nash, John F. (2009a). "Ideal money and asymptotically ideal money." Contributions to Game Theory and Management. Volume II.

- Nash, John F. (2009b). "Studying cooperative games using the method of agencies." International Journal of Mathematics, Game Theory, and Algebra.

- Nash, John F., Jr., Nagel, Rosemarie, Ockenfels, Axel, & Selten, Reinhard (2012). "The agencies method for coalition formation in experimental games." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Some of Nash's important papers were collected in:

- Kuhn, Harold W., & Nasar, Sylvia (Eds.). (2002). The essential John Nash. Princeton University Press.

See also

In Spanish: John Forbes Nash para niños

In Spanish: John Forbes Nash para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |