John Roberts facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Roberts

|

|

|---|---|

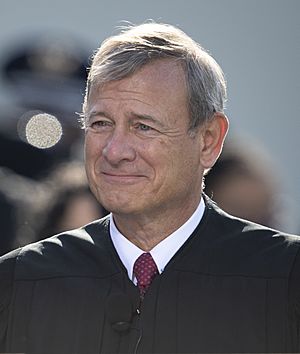

Official portrait, 2005

|

|

| 17th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| Assumed office September 29, 2005 |

|

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | William Rehnquist |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office June 2, 2003 – September 29, 2005 |

|

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | James L. Buckley |

| Succeeded by | Patricia Millett |

| Principal Deputy Solicitor General of the United States | |

| In office October 24, 1989 – January 20, 1993 |

|

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Donald B. Ayer |

| Succeeded by | Paul Bender |

| Associate Counsel to the President | |

| In office November 28, 1982 – April 11, 1986 |

|

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | J. Michael Luttig |

| Succeeded by | Robert Kruger |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Glover Roberts Jr.

January 27, 1955 Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Jane Sullivan

(m. 1996) |

| Children | 2 (adopted) |

| Education | Harvard University (BA, JD) |

| Awards | Henry J. Friendly Medal (2023) |

| Signature | |

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and judge who serves as the 17th chief justice of the United States. As chief justice, he is the head of the Supreme Court, the highest court in the nation. He is often described as a moderate conservative judge.

Roberts was born in Buffalo, New York, and grew up in Indiana. He was an excellent student and went to Harvard University for both college and law school. After graduating, he worked for famous judges and later held important jobs in the U.S. government under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. He became a very successful lawyer, arguing 39 cases before the Supreme Court.

In 2003, President George W. Bush appointed Roberts to be a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. In 2005, Bush nominated him to the Supreme Court. After Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, Bush nominated Roberts to become the new chief justice. The Senate confirmed him, and at age 50, he became the youngest chief justice since John Marshall in 1801.

As chief justice, Roberts has written the main opinions in many important cases. These cases have dealt with topics like health care, voting rules, and the powers of the president. He also presided over the first impeachment trial of President Donald Trump.

Early Life and Schooling

John Glover Roberts Jr. was born on January 27, 1955, in Buffalo, New York. His father, John Sr., was an engineer at a steel company, and his mother was Rosemary. He has two younger sisters, Margaret and Barbara. When he was ten, his family moved to Long Beach, Indiana.

Roberts went to La Lumiere School, a private Catholic boarding school in Indiana. He was a top student and also very active in sports. He was the captain of the football team and a champion wrestler. He also participated in choir and drama and was a co-editor of the school newspaper. In 1973, he graduated as the valedictorian, which means he had the best grades in his class.

College and Law School

Roberts attended Harvard College, where he studied history. He was such a good student in high school that he started college as a sophomore (a second-year student). He won awards for his writing and was known as a serious and dedicated student. He graduated in 1976 with the highest honors.

Although he thought about becoming a history professor, he decided to go to Harvard Law School for better career opportunities. In law school, he was again one of the top students. He became the managing editor of the Harvard Law Review, a very important student-run legal journal. He graduated with high honors in 1979.

Starting His Legal Career

After law school, Roberts worked as a law clerk for two very respected judges. First, he clerked for Judge Henry Friendly and then for Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist. A law clerk is a young lawyer who helps a judge with research and writing.

In 1981, Roberts began working for the government in the administration of President Ronald Reagan. He worked in the Department of Justice and later as a lawyer in the White House.

In 1986, he left the government to work at a private law firm called Hogan & Hartson in Washington, D.C. He became a top appellate lawyer, which means he argued cases in higher courts, including the Supreme Court. An appellate lawyer tries to persuade judges to change a decision made by a lower court.

Working for the Government Again

In 1989, Roberts returned to government work under President George H. W. Bush. He served as the Principal Deputy Solicitor General. The Solicitor General's office represents the U.S. government in cases before the Supreme Court. In this role, Roberts argued many important cases for the government.

In 1992, President Bush nominated Roberts to be a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, but the Senate did not vote on his nomination before the presidential election. So, in 1993, Roberts returned to his law firm, Hogan & Hartson. He continued to be one of the most respected lawyers arguing before the Supreme Court.

Judge on the D.C. Circuit Court

In 2001, President George W. Bush nominated Roberts again for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. This court is often seen as a stepping stone to the Supreme Court. After a delay, the Senate finally confirmed him in 2003.

During his two years as a circuit judge, Roberts wrote 49 opinions. His writing was known for being clear and crisp. One well-known case involved a 12-year-old girl who was stopped by police for eating a french fry in a Washington, D.C. metro station. Roberts wrote the opinion for the court, which found that the police had acted properly under the metro's "zero tolerance" policy against eating.

Supreme Court Nomination

In July 2005, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor announced she would retire from the Supreme Court. President Bush nominated Roberts to take her place.

However, while Roberts's nomination was being considered, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist died on September 3, 2005. Two days later, President Bush withdrew Roberts's first nomination and instead nominated him to become the new Chief Justice.

The Senate held hearings to ask Roberts questions about his views on the law. He famously compared the job of a judge to a baseball umpire. He said, "[I]t's my job to call balls and strikes, and not to pitch or bat." This meant he saw his role as applying the rules fairly, not creating them.

On September 29, 2005, the full Senate voted to confirm Roberts as Chief Justice by a vote of 78–22.

Chief Justice of the United States

Roberts took his oaths of office on September 29, 2005, becoming the leader of the Supreme Court. The period during which a particular chief justice leads the court is often named after them, so the current court is known as the "Roberts Court."

As chief justice, Roberts presides over the court's public sessions and private conferences where the justices discuss and vote on cases. He has a reputation for trying to build agreement among the justices and for his belief in judicial minimalism. This is the idea that judges should make narrow rulings and avoid making big changes to the law unless absolutely necessary.

In 2018, Roberts made a public statement defending the independence of the judicial branch. After President Donald Trump called a judge who ruled against him an "Obama judge," Roberts said, "We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them."

Notable Decisions

As chief justice, Roberts has written the majority opinion in many landmark cases.

- Health Care: In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), he wrote the 5–4 opinion that upheld the main part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, a major health care reform law.

- Presidential Power: In Trump v. Hawaii (2018), he wrote the opinion that upheld the president's power to issue a travel ban. In Trump v. United States (2024), he wrote the opinion outlining when a former president is protected from criminal charges for actions taken while in office.

- Digital Privacy: In Carpenter v. United States (2018), he wrote the majority opinion stating that the government generally needs a warrant to get location data from a person's cell phone.

- Voting Rights: Roberts has been in the majority on several important cases about the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Court struck down a key part of the act that required certain states with a history of discrimination to get federal approval before changing their voting laws.

- School Admissions: In Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023), Roberts wrote the majority opinion that limited the use of race as a factor in college admissions.

Personal Life

Roberts married Jane Sullivan in 1996. She is also a lawyer and a legal recruiter. They met in New York. They live in Chevy Chase, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C., and have two adopted children, a son and a daughter.

Health

In 2007, Roberts had a seizure while at his vacation home in Maine. Doctors could not find a specific cause. He had a similar seizure in 1993. In 2020, he had a fall and was hospitalized overnight for observation. Doctors believed he was dehydrated and ruled out another seizure.

Awards and Honors

In 2007, Roberts received an honorary degree from the College of the Holy Cross. In 2023, he was awarded the Henry J. Friendly Medal by the American Law Institute, an award named after the first judge he worked for.

See Also

In Spanish: John Roberts para niños

In Spanish: John Roberts para niños

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Chief Justice)

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

- List of United States chief justices by time in office

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases decided by the Roberts Court

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |