John Mawurndjul facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Balang Nakurulk

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1952 Mumeka, Northern Territory, Australia

|

| Died | 21 December 2024 |

| Other names | Mowundjul, Mawandjul, Mowandjul, Mowundjal, Mawundjurl, Mawurndjurl, Johnny Mawurndjul |

| Known for | Bark painting, contemporary Indigenous Australian art |

| Spouse(s) | Kay Lindjuwanga |

| Parent(s) | Anchor Kulunba, Mary Wurrdjedje |

| Relatives | Pamela Djawulba (daughter), Anna Wurrkidj (daughter), Josephine Wurrkidj (daughter), Semeria Wurrkidj (daughter) |

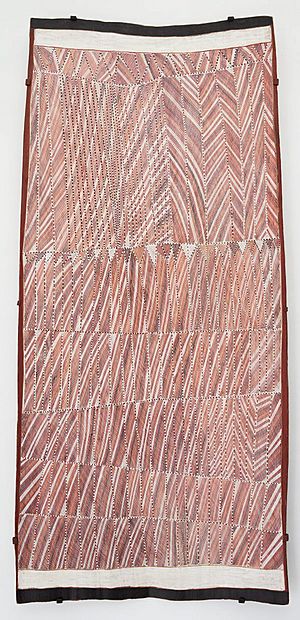

Balang Nakurulk (1952–2024) was a very famous Indigenous Australian artist. He used old traditions in new ways to show important spiritual and cultural ideas. He was especially known for his unique bark painting style called rarrk. This style uses fine cross-hatching lines. Balang also created carvings, woven items, and batik art.

Contents

About Balang's Life

Balang was born in 1952 in Mumeka, Australia. This was a traditional camping spot for his family, the Kurulk clan. It was located about 50 kilometers (31 miles) south of Maningrida. He belonged to the Kuninjku people of West Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.

Balang grew up living a traditional life with his large family. He had very little contact with people from outside his culture. He lived on his family's land, moving between camps along the Liverpool, Mann, and Tomkinson Rivers. This area is a tropical woodland, rich in plants and animals. It also has ancient rock art galleries.

As of May 2010, Balang was still living a traditional life near Maningrida. He continued to paint and hunt. He was known as a great hunter and was seen as a very talented artist from a young age.

Learning to Paint

Balang started learning ritual painting in 1969 from his father, Anchor Kulunba. He learned to paint rarrk on bodies and special objects for ceremonies. Later, his older brother Jimmy Njiminjuma and Peter Marralwanga taught him more about bark painting.

He learned how to collect and prepare the bark. He also learned how to find special ochre (natural earth pigments) and mix them to make paints. He even learned to make delicate brushes from sedge rushes. Balang became very skilled at these traditional art forms.

Anthropologist Luke Taylor studied Kuninjku art and said Balang helped change their art traditions. Balang brought ceremonial designs into modern art. Taylor also described Balang as an energetic person and a great hunter who shared food with his family.

Life Changes and Art

Balang grew up when the Australian government started to have more influence in Arnhem Land. This affected his art. Villages and towns grew, changing the lives of Indigenous people. Balang's art often explored these changes.

His artworks use Kuninjku knowledge to share stories, laws, and ceremonies. Balang was married to another artist, Kay Lindjuwanga. Their daughters, Anna Wurrkidj, Josephine Wurrkidj, and Semeria Wurrkidj, also became artists. His family continues to keep Kuninjku art traditions alive.

Balang was also a leader in many religious traditions. In the early 1990s, he and his family settled near a billabong (a small lake) called Milmilngkan. This lake was a sacred place for the Ngalyod, a rainbow serpent. Balang often showed Ngalyod in his artwork.

Balang's Art Style

Balang is famous for his use of rarrk, a cross-hatching style from Arnhem Land. He used this technique to create amazing visual effects. His rarrk paintings often make you feel a little unsure of what you're seeing. The lines seem to move and shimmer.

This shimmering effect is called bir'yin in Kuninjku. It means "brilliance" or "shining." It reminds people of wangarr marr, which is ancestral power. For Balang, these patterns were not just pretty. They showed the strength of ancestral power and had a spiritual purpose.

Balang's use of rarrk was a big step forward in bark painting. He was one of the first bark painters to become well-known in the modern art world. He found new ways to show space and depth using his cross-hatching. His art mixed old techniques with his own new ideas.

His later works sometimes included circle shapes on top of the rarrk patterns. These circles seemed to "float" and added more meaning. In his Madayin series, these circles looked like waterholes. Waterholes are also believed to hold ancestral powers. Balang said that "Mardayin phenomena are located in water... it is always in the water."

Balang learned rarrk from his uncle Peter Marralwanga and brother Jimmy Njiminjuma in the 1970s. He started by making small bark paintings of animals and spirits. These included echidnas, saratoga fish, barramundi fish, mimih spirits, yawkyawk, and Ngalyod (the Rainbow Serpent).

He also helped create mimih sculptures, which are spirit figures carved from softwood. These were important in the Maningrida region. By the 1980s, he started making bigger and more complex artworks. In 1988, he won an award and his work began to be shown in many exhibitions.

Balang found inspiration from other artists and from sacred places on his ancestral lands. Before starting new works, he would look across the Kurulk clan estate for ideas.

New Ideas in Traditional Art

Balang used many different techniques throughout his career. Some were from his culture, and others he created himself. Early on, he painted important Aboriginal figures like the rainbow serpent Ngalyod. Later, he used more "geometric" shapes, inspired by Mardayin ceremony body paintings.

His 1988 painting Nawarramulmui (Shooting Star Spirit) shows this geometric style. It uses straight lines and solid colors instead of rarrk, but it's still on bark. This painting also connects to his culture, representing a supernatural figure. Many of Balang's paintings are like maps of his ancestral lands and show sacred sites.

Balang explained that his geometric experiments were not to move away from traditional ceremonies. Instead, he used them to avoid showing secret meanings in art sold to the public. He wanted to share his art while staying true to Kuninjku culture. He only included ceremonial designs that were okay to share.

While bark painting was his main art form, Balang also made carved figures and lorrkon (hollow log coffins). He painted these with his detailed imagery. All the materials for his art, like bark, ochres, and brushes, came from his own land.

Balang deeply respected his traditions, but he also loved finding new ways to express himself. He said, "I have my own style, my own ideas. I always think of new ways to paint, I always look for something different."

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout the 1990s, Balang's art was shown in major exhibitions of Aboriginal Australian art. These included Dreamings in New York City (1988) and Magiciens de la Terre in Paris, France (1989). His work also traveled to Japan, Germany, and the UK.

In 2000, Balang's art was part of an exhibition at the famous Hermitage Museum in Russia. Russian critics praised the show, saying it was "contemporary art" in its ideas and philosophy. His work was also featured at the Sydney Biennale in 2000.

In 2004, an exhibition called Crossing Country showed 22 of Balang's works. It explored how artists from western Arnhem Land influenced each other.

In 2006, Balang created a ceiling mural and a carved Lorrkkon funerary pole for the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris. These works had deep Kuninjku cultural meaning. The water lily, a symbol of spiritual connection and rebirth, was often seen in his work. After finishing this work, the French president, Jacques Chirac, called Balang the 'maestro'. Balang was even photographed in front of the Eiffel Tower for Time magazine.

His art was also shown in big exhibitions in Basel, Switzerland (2005) and Hanover, Germany (2006). This made Balang the first Australian artist to have major shows at two leading European museums.

In 2018–2019, a large exhibition of his work, John Mawurndjul: I Am the Old and the New, was shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney. This exhibition showed his bark paintings and highlighted his spiritual heritage. It explored how bark painting can be both ancient and new at the same time. Balang helped organize this exhibition, and it was described in both Kuninjku and English.

Balang always said his art was deeply connected to his ancestors, land, and country. He stated, "I am only painting the land. I paint the power of that land. They are big places, sometimes dangerous and have a lot of power." His paintings are rooted in traditional ceremonies but also fit into the global art world.

Balang's Legacy

Balang lived in Milmilngkan, his ancestral lands, where he took part in ceremonies. He used materials from his land for both art and daily life. Milmilngkan was a very important place in his art, connecting his life and art to his ancestors.

Through his art, Balang became the first Australian artist to have major exhibitions at two different European museums. His work was shown at the Tinguely Museum in Basel, Switzerland (2005), and the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, Germany (2006).

Balang helped choose the artworks for his exhibitions. He wanted them arranged by kunred, which are special cultural areas for the Kuninjku people. This helped make him a globally recognized artist, connecting Indigenous Australian art with the European art world.

Balang's art was inspired by Mardayin ceremonies, which are very important in his culture. He used patterns and shapes to tell the stories behind them, keeping secret meanings hidden. Even though his art is based on old stories, his abstract designs and detailed patterns let people from all over the world connect with it.

Balang is seen as a modern artist in Australia, France, and around the world. He was known for trying new projects, working with researchers, and his energy for painting.

Balang had a big influence on other Kuninjku artists. He taught his wife, Kay Lindjuwanga, and his daughter Anna Wurrkidj, who are now skilled painters. He helped create a whole group of artists and led an Australian art movement. Balang died peacefully in Maningrida on December 21, 2024.

Awards and Recognition

Balang received many awards throughout his career.

- In 1988, he won the Rothmans Foundation Award for best traditional painting.

- He won the bark painting prize at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 1999, 2002, and 2016.

- In 2003, Balang won the important Clemenger Contemporary Art Award. This award recognized his big contributions to modern Indigenous art in Australia. Balang felt this award showed that "Aboriginal art and non-Aboriginal art were now considered ‘level’."

- In 2010, Balang became a Member of the Order of Australia. This was for his work in keeping Aboriginal culture and art alive through his paintings.

- In 2018, he received the Red Ochre Award, which is given to outstanding Indigenous Australian artists for their lifetime achievements.

Balang was also featured in several books about Aboriginal art. He was on the cover of UNTITLED. Portraits of Australian Artists in 2007. His reputation as a celebrated artist from Arnhem Land led to many publications about his work.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | himself | Red Ochre Award | Awarded |

Art Collections

Balang's artworks are held in many important art collections around the world, including:

- Sprengel Museum, Hanover, Germany

- Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, The Netherlands

- British Museum, UK

- Musée du quai Branly, Paris, France

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia

- National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia

- Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

- Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

- Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia, USA

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |