John Shelton (British Army officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Shelton

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | 1790/91 |

| Died | (aged 54) Dublin |

| Buried |

St Peter's Church, Dublin

|

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

British Army |

| Years of service | 1805–45 |

| Rank | Colonel (Major General in the British Indian army) |

| Unit | 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot |

| Wars | Peninsular War Walcheren Campaign War of 1812 First Anglo-Burmese War First Anglo-Afghan War |

Colonel John Shelton (born 1790 or 1791 – died May 13, 1845) was an officer in the British Army. He led the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot during the First Anglo-Afghan War. He was also the second-in-command to Major General Sir William Elphinstone.

Shelton was one of the few British soldiers who survived the terrible 1842 retreat from Kabul. In this event, a British army group of 4,500 soldiers and 12,000 civilians was attacked by Afghan fighters. This happened as they tried to march to Jalalabad. Shelton was known as a very strict and difficult commander. Many believed his mistakes led to his regiment being almost completely destroyed. Despite this, he was also known for his great bravery in battle.

Contents

Early Army Days

John Shelton joined the army as a young officer (an ensign) on November 21, 1805. He was part of the 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot. Two years later, he became a lieutenant.

In 1808, he fought in battles in Portugal, including Roliça, Vimiero, and Corunna. His regiment then returned to Britain. Shelton also took part in the difficult Walcheren expedition in 1809.

He went back to the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) in 1812–13. During these years, he fought in battles like Badajoz, Burgos, Salamanca, and Vittoria. He was badly wounded during the siege of San Sebastián, losing his right arm. People said he stood calmly while a surgeon removed his arm.

In 1817, Shelton moved to the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot. He was sent to India in 1822. His regiment fought in Arakan, Burma, in March 1824 during the First Anglo-Burmese War. Shelton showed great courage there. A year later, on February 6, 1825, he became a major in the regiment. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel on September 16, 1827. For the next 13 years in India, he gained a reputation as a very strict and demanding leader.

Service in Afghanistan

In late 1840, Shelton was temporarily promoted to major general. This happened when his regiment joined two Indian units. They formed a group to help the British forces in Afghanistan. In the first half of 1841, his brigade first went to Jalalabad. Then, they went on a mission into the Nazian valley. This opened the Khyber Pass for Shuja Shah Durrani's family to cross into India. Finally, they reached Kabul on June 9.

Shelton quickly became unpopular with his fellow officers and soldiers. He often didn't want to attend meetings with the British commander, Sir William Elphinstone. He rarely answered Elphinstone's questions and was generally difficult with everyone. He treated his men harshly and was seen as "a tyrant to his regiment."

Captain Colin Mackenzie watched Shelton's journey through Afghanistan. He wrote that Shelton was "a terrible brigadier." Mackenzie noted the "huge confusion" when crossing rivers because Shelton didn't plan well. This would have been dangerous in enemy territory. Later, Mackenzie saw the brigade after it returned from the Khyber Pass. He wrote that Shelton had "marched the brigade off its legs." The horses were exhausted, and many camels died from overwork. The unnecessary hardships Shelton put the men through caused much unhappiness. At one point, part of the horse artillery even refused to obey orders.

Uprising in Kabul

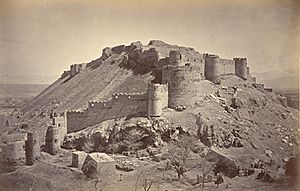

On November 2, 1841, an uprising began in Kabul. The senior British officer, Sir Alexander Burnes, and his helpers were killed. Shelton was camped two miles east of the city. He was ordered to take control of Kabul's fortress, the Bala Hissar. But he seemed very confused when he got the order. Captain George Lawrence wrote that Shelton "seemed almost beside himself, not knowing how to act."

Despite Shelton's doubts, his troops reached the Bala Hissar without any problems. They stayed there for the next week. Even though the fortress was strong, he believed they couldn't survive a siege there. He suggested the British force should leave Kabul and go to Jalalabad. This would mean abandoning Kabul and the pro-British Shah Shuja.

Shelton's force left the fortress and moved to a military camp (cantonment) outside the city. He knew it was not well protected. He called its defenses "a rampart and ditch an Afghan could run over with the ease of a cat." He failed to protect another fort that held the British army's food supplies. He had 5,000 men who could have done this job. Mohan Lal, who was Burnes's secretary, later wrote that Shelton "seemed from the start to lose hope of success." This had a bad effect on all the soldiers.

The food supply fort was lost. On November 10, Shelton led an attack on another fort, the Rikab Bashee. The rebels had taken this fort too. It took two attempts and over a hundred casualties before the 44th Foot took the fort. After the Afghans placed two cannons on the Bimaru Hills, Shelton led an attack to drive them away. It was successful at first, but the hills were soon taken back.

Battle of the Bimaru Hills

Ten days later, Shelton took his men out again to retake the hills. This second attack was a disaster. The Afghans' long-barreled jezail rifles could shoot farther than the British Brown Bess muskets. Shelton did not try to dig trenches to protect his men from enemy fire. Instead, he made the troops stand for hours in rows on top of the hill. They were completely exposed to enemy fire. Afghan snipers shot them down one by one, but Shelton refused to retreat.

The battle quickly turned into a terrible defeat. Out of 1,100 men on the hill, 300 were killed there. Many more were cut off and killed during the retreat back to the camp. George St. Patrick Lawrence watched from the camp. He wrote about his horror seeing "our fleeing troops hotly pursued and mixed up with the enemy." He said the scene was "so fearful that I can never forget it." He strongly criticized Shelton's "total inability to command." He felt Shelton's "reckless exposure of his men" led to the disaster.

Retreat and Capture

Shelton himself survived the terrible loss of his troops, though he was wounded five times in the battle. His failure at Bimaru greatly hurt the soldiers' spirits. Captain Mackenzie wrote that Shelton's inability to lead "neutralised the heroism of the officers." He said their spirit was gone and discipline had almost disappeared. No more attempts were made to push back the Afghans.

Shelton, who was promoted to full colonel after the battle, argued that they should retreat to Jalalabad before winter snows came. However, Elphinstone waited for almost a month before trying to negotiate with the Afghan side. The British messenger, Sir William Hay Macnaghten, was killed two weeks into the talks. On January 6, the retreat began.

Thousands of soldiers and civilians died over the next five days. The slow-moving British group was attacked repeatedly by the Afghans. By January 11, 12,000 out of the 16,500 people in the group had been killed or wounded. Only 200 soldiers remained as the survivors entered the small village of Jagadalak. Shelton was among them, fighting bravely even with only one arm. Captain Hugh Johnson wrote: "Nothing could exceed the bravery of Shelton." He fought like "a bulldog attacked on all sides."

Johnson went with Shelton and Elphinstone to meet the Afghan leader, Wazir Akbar Khan. But all three men were taken prisoner. A very angry Shelton demanded to be allowed to return to his men and die fighting, but he was refused. The rest of the group was left to defend themselves. They were almost all killed at Gandamak. Only one badly wounded European, Assistant Surgeon William Brydon, and a few Indian soldiers (sepoys) managed to reach Jalalabad on January 13.

Aftermath and Death

Shelton was one of 32 British officers and many captured soldiers, women, and children. They were held by Akbar Khan for several months after the battle. The captives were treated well, but Shelton seemed to struggle with being a prisoner. He soon became disliked by the other captives because he argued a lot. Captain Souter, an officer from his regiment, wrote that Shelton "looks the picture of misery." Elphinstone died in captivity, making Shelton the highest-ranking British survivor.

The captives were freed on September 21. However, Shelton was arrested by Lord Ellenborough, the Governor-General of India. He faced a military trial (court-martial) in Ludhiana on January 31, 1842. He was accused of four things. The main charge was that he had "too early, and without permission" ordered ammunition wagons to be emptied. He had them filled with food for the retreat from Kabul, without Elphinstone's approval. The other three charges were less serious. They included using disrespectful language about Elphinstone in front of troops, getting food for his horses from Akbar Khan, and allowing himself to be captured at Jagdalak.

Despite Shelton's clear mistakes, he was found innocent of three of the four charges. He was found guilty of the least serious one: getting food for his horses without permission. But he wasn't punished because the court felt he had already been told off enough by Elphinstone.

Even though the court said Shelton had shown "very considerable effort in his difficult position, of personal bravery of the highest kind, and of noble devotion as a soldier," some of his fellow officers strongly criticized him. General Charles Napier wrote harsh comments about Shelton. Napier believed Shelton was "the author of all ill" and "unfit to command."

Shelton went back to leading the 44th Foot. The regiment had to be rebuilt because it was almost completely destroyed during the retreat. He was no more popular with his new soldiers than he had been before. On May 10, 1845, while his regiment was in Dublin's Richmond Barracks, his horse suddenly ran off while he was riding it. He was badly injured and died three days later. When his men heard he had died, they gathered on the parade ground and cheered. He never received any medals or awards for his many military campaigns.

His burial took place at St Peter's Church in Dublin. The church was torn down in 1983.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |