Johns Hopkins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Johns Hopkins

|

|

|---|---|

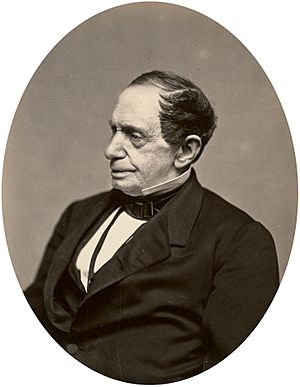

Hopkins, c. 1871

|

|

| Born | May 19, 1795 Gambrills, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Died | December 24, 1873 (aged 78) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Entrepreneur, investor, philanthropist |

| Signature | |

|

|

Johns Hopkins (born May 19, 1795 – died December 24, 1873) was an American businessman, investor, and generous giver (philanthropist). He was born on a large farm and left home at age 17 to start his career. He settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he lived for most of his life.

Hopkins invested a lot of money in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). This led to him becoming the finance director for the company. He was also the president of the Merchants' National Bank in Baltimore. Hopkins strongly supported Abraham Lincoln and the Union during the American Civil War. He often let Union leaders meet at his home in Maryland. He was a Quaker and supported the movement to end slavery, known as abolitionism.

Johns Hopkins was a philanthropist throughout his life. His giving increased a lot after the Civil War. He cared deeply about poor people and newly freed slaves. He wanted to create free medical places, orphanages, and schools to help everyone, no matter their race, gender, age, or religion. He especially focused on helping young people. After he died, his bequests (gifts in his will) were used to start many important places named after him. The most famous are Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University system. This includes the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. At the time, his gift was the largest amount of money ever given to an American school.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795, at his family's home called White's Hall. This was a 500-acre tobacco farm in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. He was named after his grandfather, Johns Hopkins. He was one of eleven children born to Samuel Hopkins and Hannah Janney.

His family was of English background and were Quakers. In 1778, his family freed the enslaved people they owned. This was because their Quaker group decided that enslaved people should be freed. Johns worked on the farm with his brothers and sisters, as well as with other workers. From 1806 to 1809, he probably went to The Anne Arundel County Free School.

In 1812, when he was 17, Johns left the farm. He went to work in his uncle Gerard T. Hopkins's grocery business in Baltimore. His uncle was a well-known merchant. While living with his uncle's family, Johns and his cousin, Elizabeth, fell in love. However, Quaker rules strongly prevented first cousins from marrying. Because of this, neither Johns nor Elizabeth ever got married.

Johns Hopkins helped his family throughout his life and after his death. He left a home for Elizabeth in his will, where she lived until she died. He also gave money and a house to his longest-serving helper, James Jones. He gave money to two other helpers as well.

His Business Career

Hopkins first found success in business when he was put in charge of his uncle's store. This happened while his uncle was away during the War of 1812. After working for his uncle for seven years, Hopkins started a business with Benjamin Moore, another Quaker. This partnership later ended because Moore said Hopkins was too focused on making money.

After Moore left, Hopkins started a new business in 1819 with three of his brothers. It was called Hopkins & Brothers Wholesalers. The company did well by selling different goods in the Shenandoah Valley. They used Conestoga wagons and sometimes traded goods for corn whiskey. This whiskey was then sold in Baltimore as "Hopkins' Best."

However, most of Hopkins's wealth came from smart investments. He invested a lot in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). He became a director of the B&O in 1847 and chairman of its Finance Committee in 1855. He was also the President of Merchants' Bank and a director of other companies. After a very successful career, Hopkins was able to retire in 1847 at age 52.

Hopkins was a very giving person. He used his own money more than once to help Baltimore City during money problems. He also helped the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company out of debt twice, in 1857 and 1873.

In 1996, Johns Hopkins was ranked 69th in a list called "The Wealthy 100." This list looked at the richest Americans throughout history.

During the Civil War

One of the first plans for the American Civil War was made at Hopkins' summer home, Clifton. He had also hosted important visitors there, including the future King Edward VII. Hopkins strongly supported the Union. This was different from some people in Maryland who sided with the South and the Confederacy. During the Civil War, Clifton became a regular meeting place for Union supporters and government officials.

Hopkins' support for Abraham Lincoln often caused disagreements with some important people in Maryland. This included Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney, who disagreed with Lincoln's decisions. In 1862, Hopkins wrote a letter to Lincoln. He asked Lincoln to ignore those who disagreed and keep soldiers in Maryland. Hopkins also promised to help Lincoln with money and supplies. He offered the free use of the B&O railway system.

His Views on Slavery

In 2020, researchers at Johns Hopkins University found new information. They discovered that Johns Hopkins might have owned or used enslaved people who worked in his home and on his country estate. This information came from census records from 1840 and 1850.

Because of this, Hopkins's reputation as someone who wanted to end slavery (an abolitionist) is now being discussed. Johns Hopkins University sent an email in December 2020 about this. They said that new research did not find proof that Johns Hopkins was an abolitionist. They also found that his grandfather had freed some enslaved people in 1778, but the family continued to own enslaved people for decades after that. They found a letter from 1838 where Hopkins's business accepted an enslaved person as payment for a debt. However, they also found an old newspaper article that said Johns Hopkins had anti-slavery political views. This article also said he bought an enslaved person to set them free later. Other old documents show that important Black leaders praised Hopkins for planning to build an orphanage for Black children.

Another group of experts disagrees with the university's findings from December 2020. They say that Johns Hopkins's parents and grandparents were Quakers who freed their enslaved workers before 1800. They believe Johns Hopkins supported ending slavery within the laws of Maryland at the time. They also say that tax records they found do not support the idea that Johns Hopkins owned enslaved people himself.

Before these new discoveries, Johns Hopkins was often described as an "abolitionist." He was seen this way before, during, and after the Civil War. Before the war, he worked with famous abolitionists like Myrtilla Miner and Henry Ward Beecher. During the Civil War, his strong support for Lincoln and the Union helped Lincoln's plans to free enslaved people.

After the Civil War, Hopkins's views on ending slavery made many important people in Baltimore angry. His support for abolitionism was shown in the documents that started the Johns Hopkins Institutions. Newspapers also reported on his views. Before the war, many people disagreed with his support for Myrtilla Miner's school for African American girls.

Newspapers also showed both disagreement and support for his actions during the Reconstruction era. For example, in 1867, he tried to stop a meeting where a new state Constitution was voted on. This new Constitution replaced an older one and brought a different political party into power.

Newspapers also showed how people reacted to his efforts to fight against racial practices in Baltimore and Maryland. A journalist from the Baltimore American praised Hopkins. The journalist said Hopkins founded three institutions: a university, a hospital, and an orphanage specifically for Black children. The reporter called Hopkins "a man (beyond his times) who knew no race." This was because Hopkins planned for both Black and white people to be helped by his hospital. This article, first published in 1870, was also included in Hopkins's obituary in 1873. Many newspaper articles about him mentioned his plans to give scholarships to poor young people. They also noted his plans for good health services for those who needed them, regardless of age, gender, or race. He also planned for orphanages, including one for Black children, and care for the elderly and mentally ill.

A book about Johns Hopkins, called Johns Hopkins: A Silhouette, was written by his grand-niece, Helen Hopkins Thom. It was published in 1929. This book was one of the sources for the story that Hopkins was an abolitionist.

His Generous Gifts (Philanthropy)

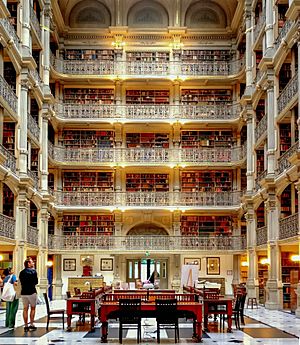

Hopkins lived his whole adult life in Baltimore. He made many friends among the city's important people, many of whom were Quakers. One of his friends was George Peabody, who also started a famous institution, the Peabody Institute, in Baltimore in 1857. Hopkins's public giving was clear in Baltimore. Public buildings like free libraries, schools, and foundations were built with his money. Some people believe that Peabody advised Hopkins to use his great wealth for the good of the public.

The Civil War and outbreaks of diseases like yellow fever and cholera greatly affected Baltimore. In the summer of 1832 alone, these diseases killed 853 people in Baltimore. Hopkins knew that the city needed more medical facilities, especially after the medical improvements made during the Civil War. In 1870, he wrote his will. He set aside seven million dollars, mostly in B&O stock. This money was for starting a free hospital and related medical and nursing schools, an orphanage for Black children, and a university in Baltimore.

The hospital and orphanage were managed by a board of 12 trustees. The university was managed by another board of 12 trustees. Many people were on both boards. Following Hopkins's will:

- The Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum opened in 1875.

- Johns Hopkins University was founded in 1876.

- The Johns Hopkins Press, the oldest continuously running academic publisher in the U.S., started in 1878.

- Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing were founded in 1889.

- The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine was founded in 1893.

- The Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was founded in 1916.

Hopkins wrote down his ideas for his gifts and the duties of the trustees in several documents. These included his incorporation papers from 1867, a letter to the hospital trustees in 1873, his will, and two additions to his will (called codicils) from 1870 and 1873.

In these documents, Hopkins planned for scholarships for poor young people in the states where he made his money. He also planned to help other orphanages, his family members, his employees, and his cousin Elizabeth. He wanted to help other places that cared for and educated young people, no matter their race. He also wanted to care for the elderly and the sick, including those with mental illness.

John Rudolph Niernsee, a famous architect, designed the orphan asylum and helped design the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Hopkins himself chose the original location for Johns Hopkins University. His will said it should be at his summer home, Clifton. However, the university was not built there. That property is now a golf course and park called Clifton Park. While the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum was started by the hospital trustees, the other Johns Hopkins institutions were founded under the leadership of Daniel Coit Gilman. He was the first president of Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Orphanage for Black Children

As Hopkins requested, the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum (JHCCOA) was founded first, in 1875. This was a year before Gilman became president of the university. The construction of the asylum, including its learning and living areas, was praised by newspapers. One newspaper said the orphanage was a place where "nothing was wanting that could benefit science and humanity." Like other Johns Hopkins institutions, it was planned after visiting and learning from similar places in Europe and the U.S.

The Johns Hopkins Orphan Asylum opened with 24 boys and girls. Later, under Gilman and his successors, the orphanage changed. It became a home and training school mainly for Black female orphans, teaching them skills for domestic work. It also became a home and school for "colored crippled" children and orphans who needed special care for their bones (orthopedics). The asylum closed in 1924, almost 50 years after it opened.

Hospital, University, and Schools

In his March 1873 letter, Hopkins also said that a school of nursing should be started with the hospital. This happened in 1889, with advice from Florence Nightingale. Both the nursing school and the hospital opened more than ten years after the orphanage (1875) and the university (1876).

Hopkins's letter clearly stated his vision for the hospital:

- First, it should help poor people of "all races," no matter their "age, sex or color."

- Second, wealthier patients would pay for services, which would help pay for the care given to poor patients.

- Third, the hospital would manage the orphanage for African American children. The orphanage would receive $25,000 each year from the hospital's funds.

- Fourth, the hospital should serve 400 patients, and the orphanage should serve 400 children.

- Fifth, the hospital should be part of the university.

- Sixth, religion should be an influence in the hospital, but not in a way that favors one specific religious group.

By the end of Gilman's time as president, many Johns Hopkins institutions had been founded. These included the university, the press, the hospital, the nursing school, the medical school, and the Colored Children Orphan Asylum. Hopkins's ideas about "sex" and "color" were very important in the early history of these institutions. The nursing school was started because Hopkins said in his 1873 letter that he wanted a training school for female nurses. He believed this would provide skilled women to care for the sick and help the whole community.

His Lasting Impact

Johns Hopkins died on December 24, 1873, in Baltimore.

After his death, The Baltimore Sun newspaper published a long article about him. It said that Johns Hopkins's life showed a rare example of someone who successfully made a lot of money and then used it in a helpful way for the public. Hopkins's role in starting Johns Hopkins University became his greatest legacy. It was the largest gift ever given to a U.S. educational institution.

Hopkins's Quaker faith and his early life experiences, including the freeing of enslaved people in 1778, had a lasting effect on him. From early in his life, Hopkins saw his wealth as something he was trusted with to help future generations. He once told his gardener, "Like the man in the parable, I have had many talents given to me and I feel they are in trust. I shall not bury them but give them to the lads who long for a wider education." His ideas were similar to Andrew Carnegie's famous Gospel of Wealth, but Hopkins had these ideas more than 25 years earlier.

In 1973, Johns Hopkins was mentioned in a book that won the Pulitzer Prize. The book was called The Americans: The Democratic Experience by Daniel Boorstin. From 1975 to 1976, a picture of Hopkins was shown at the National Portrait Gallery in an exhibit about how America became more democratic. In 1989, the United States Postal Service released a $1 postage stamp in Hopkins's honor. It was part of the Great Americans series.

See also

In Spanish: Johns Hopkins para niños

In Spanish: Johns Hopkins para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |