Kingman Island facts for kids

Kingman and Heritage Islands in the Anacostia River

|

|

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′56″N 76°57′52″W / 38.8990000°N 76.9644193°W |

| Total islands | 2 |

| Area | 40 acres (16 ha) (Kingman); 6 acres (2.4 ha) (Heritage) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (2010) |

Kingman Island (also known as Burnham Barrier) and Heritage Island are two special islands in the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C.. These islands are not natural. They were built by people using material dug up from the river. The islands were finished in 1916.

Kingman Island is next to the Anacostia River on its east side. On its west side is a lake called Kingman Lake, which is about 110-acre (45 ha) big. Heritage Island is completely surrounded by Kingman Lake.

For many years, the National Park Service managed both islands. Since 1995, the District of Columbia government has owned them. They are now managed by Living Classrooms National Capital Region. Kingman Island is split by Benning Road and the Ethel Kennedy Bridge. The southern part of the island is also split by East Capitol Street and the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge.

In 2010, the northern part of Kingman Island was home to Langston Golf Course. The southern part of Kingman Island and all of Heritage Island were mostly undeveloped. Kingman Island, Kingman Lake, and the nearby Kingman Park are named after Brigadier General Dan Christie Kingman. He used to be in charge of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Contents

How the Islands Were Formed

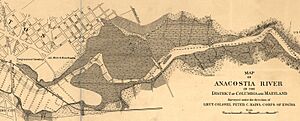

The Anacostia River Before the Islands

Before European settlers arrived in the 1700s, the Anacostia River flowed quickly. It had very little mud or marshy areas. But when white settlers cleared forests to create farmland, soil washed into the river. This made the river full of silt and pollution.

Over time, bridges were built across the Anacostia River, like Benning's Bridge. These bridges and the use of streams for farming slowed the river's flow. This caused a lot of mud and silt to settle and build up.

By the late 1800s, large mudflats formed along both sides of the Anacostia River. The city also allowed its sewage to flow directly into the river. Marsh grass grew in these mudflats, trapping the sewage. Public health experts worried that these areas were unhealthy. They also feared the mudflats were breeding grounds for malaria and yellow fever-carrying mosquitoes.

Dredging the River to Create Land

In 1898, officials decided to dredge (dig up) the Anacostia River. This would make the river deeper for ships and help the local economy. The material dug from the river would be used to fill in the muddy marshes. This would dry them out, remove health risks, and create new land. The new land could then be used for buildings or parks.

The plan was to create a channel 15 feet (4.6 m) wide on the river's west bank. The dredged material would make the new land between 14 feet (4.3 m) and 24 feet (7.3 m) high.

Building Kingman and Heritage Islands

In 1900, a group called the McMillan Commission suggested turning the newly created land into parkland. The D.C. government and other agencies agreed. Most of the reclaimed mudflats became parkland, named Anacostia Water Park (now Anacostia Park) in 1919.

The dredging work began in January 1903. In June 1912, Congress gave $100,000 to dredge the Anacostia River. By 1916, both Kingman Island and Heritage Island were completed using this dredged material.

Plans for the Islands

Ideas for a Children's Theme Park

Over the years, there were many ideas for what to do with Kingman and Heritage Islands. One big idea was to build a children's theme park. In 1991, a company proposed a large park for families on the islands. It would have walking trails and meadows, with only a small part used for buildings. People would pay an admission fee to enter.

This idea became linked to plans for a new football stadium for the Washington Redskins team. The team wanted to build parking lots on Kingman and Heritage Islands. Later, the plan changed so they would only use a small part of Kingman Island for parking.

In 1992, the Redskins owner agreed to build a new stadium in Washington, D.C. Soon after, the government agreed to give 50 acres (20 ha) of Kingman Island to the city for the children's park. The park was planned to cost $120 million. It would have science, nature, and geography exhibits, and an entertainment building. Most of the islands would still be a nature preserve. The agreement said no more than 5 acres (2.0 ha) could be used for buildings, and no building could be taller than 50 feet (15 m).

Many groups did not like the theme park idea. They worried about how it would affect the environment. Even so, the D.C. City Council approved the land transfer in 1993. But they required many studies to be done before any building could start. The stadium deal eventually fell apart, and the Redskins built their stadium in Maryland instead.

Protecting the Islands' Wildlife

The islands became important for wildlife because they were mostly undeveloped. Groups like the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund wanted to protect the islands. They said the government needed to study the environmental impact before giving the land away.

An Audubon Society survey found that over 60 species of birds lived on the islands. These included blue herons, eagles, snowy egrets, and ospreys.

In 1994, a court agreed that an environmental study was needed. But in 1996, Congress passed a law called the "National Children's Island Act." This law allowed the land to be transferred to D.C. without the environmental study. It said the land could only be used for a children's park.

However, the children's park project faced more problems. In 1999, a special board that helped manage D.C.'s money stopped the project. They said it would cost too much and was not financially possible. This decision ended the plans for the children's theme park.

In 1998, the wooden footbridge connecting Kingman Island to the western shore was burned by vandals. Most of the bridge was destroyed.

Images for kids

-

Dwight F. Davis and others break ground for the dedication of Anacostia Park in August 1923.

See also

In Spanish: Isla Kingman para niños

In Spanish: Isla Kingman para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |