McMillan Plan facts for kids

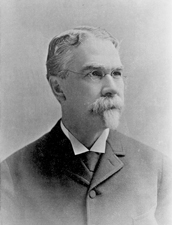

The McMillan Plan was a big plan for how Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States, should grow and look. It was created in 1902 by a group called the Senate Park Commission. This group is often called the McMillan Commission, named after its leader, Senator James McMillan from Michigan.

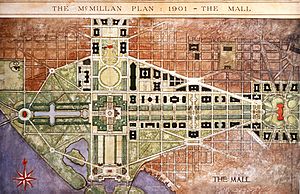

The plan suggested changing the National Mall from a winding garden into a wide, open grassy area. It also proposed building new, grand buildings like museums along the Mall. Important memorials were planned for the ends of the Mall, along with calm reflecting pools. The plan also wanted to move the old train station from the National Mall and build a huge new one north of the United States Capitol building.

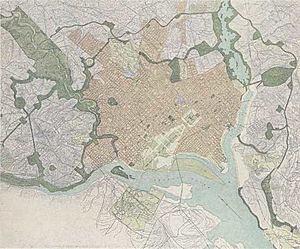

Beyond the Mall, the McMillan Plan suggested building groups of tall, classical-style office buildings near Lafayette Square and the Capitol. It also included a large system of parks and fun places for people all over the city. New roads, called parkways, would connect these parks and link the city to other interesting spots nearby.

Even though the U.S. government never officially approved the McMillan Plan, many parts of it were built over the years. The locations of the Lincoln Memorial, Ulysses S. Grant Memorial, Union Station, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Building were all chosen because of this plan. The idea for the Arlington Memorial Bridge also got a big push from the plan. The McMillan Plan still helps guide how Washington, D.C., is planned and developed today. It has become an official guide for the capital city's growth.

Contents

Why the Plan Was Created

Around 1880, many newspaper articles started criticizing Washington, D.C. People felt the city's buildings and public spaces were not very good. Then, in December 1900, a very important meeting of architects happened in Washington. They talked a lot about the city's problems and suggested ways to fix them. An architect named Paul J. Pelz even proposed ideas that later became part of the McMillan Plan. These included putting government buildings near the Capitol and planning for the National Archives Building.

The United States Senate created the Senate Park Commission on March 8, 1901. Their job was to bring together different ideas for how Washington, D.C., should be developed. They especially focused on the National Mall and nearby areas. Key members of the commission included famous architect Daniel Burnham, landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and architect Charles F. McKim. Charles Moore, Senator McMillan's main helper, became the commission's secretary. Later, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens joined the group.

Most of the commission members traveled to Europe in June 1901. They visited famous homes, gardens, and city designs. They wanted to get ideas for Washington, D.C. When they returned in August, they were ready to share their vision.

What the Plan Proposed

The commission showed their ideas to the public on January 15, 1902, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. President Theodore Roosevelt even attended the opening. The exhibit featured two huge models of Washington, D.C. One showed the city as it was in 1901. The other showed all the exciting changes the commission suggested.

The plan's report had 71 pages about the National Mall. The other 100 pages talked about improving the city's parks. The ideas for the National Mall got the most attention and were very detailed. The plans for the city's parks, beaches, and fun places were more general. The report also mentioned new streets and roads to connect parks and link the city to other areas.

The National Mall's New Look

The report suggested making the National Mall the heart of the growing city. They proposed a cross-shaped design for the Mall. The United States Capitol building would be at the east end of the east-west line. The White House would be at the north end of the north-south line. The Washington Monument would be right in the middle.

The plan suggested placing the Lincoln Memorial in West Potomac Park, at the west end of the east-west line. It also proposed moving the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial to a new plaza west of the Capitol. East Potomac Park would be at the south end of the north-south line. This area would have many recreational facilities, like a "Washington Commons."

The plan wanted to replace the old, winding gardens on the National Mall. Instead, there would be a wide, open view of grass with straight rows of trees. This would look similar to famous gardens in France. The Mall's width would be made narrower, about 300 feet (91 meters) wide. The north and south sides of the Mall would have low public buildings, museums, and theaters.

The plan also suggested a low, classical-style bridge connecting West Potomac Park to Arlington National Cemetery. Around the Washington Monument, new formal gardens and terraces would frame its base. The old train station on the National Mall would be torn down. A new, modern train station would be built north of the Capitol.

Two new reflecting pools were planned for the National Mall. One would stretch from West Potomac Park to the Washington Monument. The other would go from East Potomac Park north to the Washington Monument. The Ellipse would stay an open space. This would keep the clear view from the White House to the Washington Monument and the Potomac River.

The city's important diagonal streets would form the boundaries of this new "monumental core." Pennsylvania Avenue NW would connect the Capitol and the White House. The plan asked the government to tear down a large slum area called Murder Bay. In its place, they would build grand federal office buildings. Lafayette Square, north of the White House, would also be rebuilt with new federal buildings. Other areas would have taller federal buildings and museums.

City Parks and Parkways

The McMillan Plan also proposed a large system of parks for the city. It suggested creating many neighborhood parks, especially outside the old city limits. These parks would include public swimming areas, gyms, and playgrounds. The goal was to make parks places where everyone could exercise and enjoy nature.

A key part of the plan was developing the Anacostia Flats along the Anacostia River. This area had recently been created by adding dirt to fill in marshes. The commission suggested building roads to access the river. They also proposed a large water park for boating and swimming.

To connect the most important parks, a series of parkways were planned. These roads were designed for people in carriages (cars were not common yet) to enjoy nature. Parkways were imagined along the Potomac River, through Rock Creek Park, and to the National Zoological Park. Another parkway, called "Fort Drive," would circle the city. It would connect newly created parks that preserved historic Civil War forts around Washington, D.C.

How the Plan Was Built (or Not)

The powerful Speaker of the House, Joseph Gurney Cannon, opposed the McMillan Plan. He was upset that the Senate had created the commission without the House. He also did not want to spend the huge amount of money needed for the plan. Even though supporters tried to get public and government support, it was clear that Congress would not formally approve the plan because of Cannon.

Instead, the commission members worked hard to make sure the plan's ideas were not ignored. They waited for a better time to push for its full creation. Supporters in Congress often asked commission members to speak and defend the plan.

One major goal of the McMillan Plan was to tear down the old B&P Railroad Passenger Terminal. Many in Congress supported this idea for years. In May 1902, a law was passed to build a new Union Station. The old terminal was finally torn down in 1908.

The first big challenge to the McMillan Plan came in 1904. A new United States Department of Agriculture building was planned for the National Mall. The Department wanted to use all the space they were given. But McMillan Plan supporters argued the building should be set back from the Mall's center line. After some debate, the new Agriculture Building was built according to the McMillan Plan's setback line. It was also slightly lowered into the ground to fit its height.

The next big test was choosing the location for the Lincoln Memorial. Congress approved a Lincoln Memorial Commission in 1910. This group struggled to agree on a spot. Meanwhile, President Theodore Roosevelt wanted a permanent commission to guide art and architecture decisions based on the McMillan Plan. He created one, and later, President William Howard Taft got Congress to approve the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) in 1910. Many McMillan Plan supporters were appointed to the CFA. When the Lincoln Memorial Commission couldn't agree, they asked the CFA for help. Together, they chose West Potomac Park as the site for the new monument in June 1911.

Over the years, other decisions helped make the McMillan Plan the "official" guide for Washington, D.C.'s development. These included placing the Freer Gallery of Art in 1923. The National Capital Park and Planning Commission was created in 1926. Its job was to officially carry out the McMillan Plan. Laws were passed to enlarge the Capitol grounds in 1929, following the plan. The Capper-Cramton city park act also aimed to build the plan's park program.

The Arlington Memorial Bridge was approved in 1925. This happened after President Warren G. Harding got stuck in a three-hour traffic jam. The CFA won a long fight over the bridge's location. Congress approved the bridge's construction in the low, classical style suggested by the McMillan Plan in February 1925.

The Public Buildings Act of 1926 allowed the tearing down of the Murder Bay slum. It also approved the building of Federal Triangle in 1926. The Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway was approved in 1928. While a huge terrace around the Washington Monument was not built (it would have harmed the monument's base), the National World War II Memorial was built at the eastern end of the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool in 2004.

Recent Efforts to Use the Plan

The McMillan Plan still guides planning in Washington, D.C., today. In 1997, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) released a report called Extending the Legacy: Planning America's Capital. This report updated the McMillan Plan for the 21st century. It set new rules for where to put museums, memorials, and federal buildings.

Another big report, Monumental Core Framework Plan, came out in 2009. This report, from the NCPC and CFA, continued the McMillan Plan's ideas. It suggested creating new "federal centers" away from the main monumental area. It also proposed redeveloping the Washington Channel and Anacostia River waterfronts.

A project called CapitalSpace also started in 2009. This project aims to complete six major unfinished parts of the McMillan Plan. These include connecting the Fort Circle Parks with trails, improving recreational facilities, and creating new playgrounds. It also focuses on protecting natural areas and making small parks into lively neighborhood centers.

In late 2012, two large projects began to follow the Extending the Legacy plan. One project, "The Wharf," is a $1.45 billion plan to redevelop the waterfront along the Washington Channel. It will build many new buildings, a cultural center, and a public park. New piers will also be built.

The second project is a $906 million plan to replace the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge. It will build a new, wider bridge and new road connections. A large traffic circle will connect the north end of the bridge. Another large traffic circle on the south end will help extend the city's "monumental core" into Anacostia. These projects also include remodeling South Capitol Street and renovating New Jersey Avenue SE.

Parts of the Plan Never Built

Several parts of the McMillan Plan were never built.

One main idea was a large system of granite and marble terraces and steps around the base of the Washington Monument. These "Washington Monument Gardens" were never built. It was found that building them would require moving too much earth. This would have made the monument's foundations unstable. In 2011, a competition was held to redesign the Washington Monument grounds. The winning plan would lightly terrace the grounds.

Another unbuilt idea was a group of tall, classical-style office buildings around Lafayette Square. This plan was not completed because the government was busy building the Federal Triangle complex. Also, the Great Depression and World War II made it hard to get money, materials, and workers. In 1960, there was an effort to tear down historic homes around Lafayette Square. But First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy stopped it. She worked to keep the old buildings. Instead, two federal office buildings were built behind the smaller, historic structures. These were the New Executive Office Building (1965) and the Howard T. Markey National Courts Building (1967). They were not classical in style.

A third main unbuilt idea was a large recreational area called "Washington Commons." This was planned for East and West Potomac Parks, along the south side of the Tidal Basin. The McMillan Plan imagined many public swimming areas, athletic fields, gyms, and a stadium here. A new memorial was also planned for this area. However, the Great Depression meant there was no money to build it. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed building a memorial to Thomas Jefferson on the south side of the Tidal Basin. The Jefferson Memorial was completed in 1943.

The proposed "Fort Circle Drive" was another part of the plan that was never built. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy pushed Congress to build it. But people wondered if the plan was still useful. They argued that the city had grown past the forts, and roads already connected the parks. The idea to link the Civil War fort-parks with a grand drive was quietly dropped.

Finally, the McMillan Plan suggested grouping many government office buildings around the United States Congress. This was meant to make the Capitol area look balanced. It would also make it easier for government workers to serve Congress. No executive branch office buildings were ever built in this way. Some buildings were built nearby, but they did not follow the plan's symmetrical design. These included the Longworth House Office Building (1933), the United States Supreme Court Building (1935), and the John Adams Library of Congress Building (1939). Later buildings, like the James Madison Library of Congress Building (1976) and the Hart Senate Office Building (1982), were built in a more modern style. They did not fit well with the older, classical buildings.

While many neighborhood parks were created in Washington, D.C., the plan's full vision for parks was not achieved. The D.C. government was responsible for building these parks. But it did not have enough money to buy all the land needed. As the city grew quickly, land prices went up. The city could not get as much land as it wanted. This inability to build all the parks is seen as the biggest failure of the McMillan Plan.