Kojo Tovalou Houénou facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kojo Tovalou Houénou

|

|

|---|---|

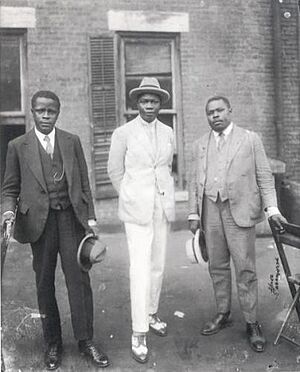

George O. Marke (left), Kojo Tovalou Houénou, Marcus Garvey (right), 1924

|

|

| Born |

Marc Tovalou Quénum

25 April 1887 |

| Died | 13 July 1936 (aged 49) |

| Citizenship | French (from 1915) |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for | Critic of French African empire, writer, Prince of Dahomey |

| Title | Prince of Dahomey |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Tovalou Quénum |

Kojo Tovalou Houénou (born Marc Tovalou Quénum; 25 April 1887 – 13 July 1936) was an important African leader. He spoke out against the French colonial empire in Africa. He was born in Porto-Novo, which is now part of Benin. His father was wealthy, and his mother was from the royal family of the Kingdom of Dahomey.

When he was 13, Kojo was sent to France for school. He studied law and medicine there. During World War I, he served as an army doctor for France. After the war, he became well-known in Paris. He wrote books and met many important people.

In 1921, he visited Dahomey again. He saw the problems there and wanted to improve relations between France and its colonies. In 1923, he was attacked in a French nightclub by Americans who didn't want an African person there. This event changed his views. He became more active in fighting racism.

He started an organization and a newspaper with other African thinkers in Paris. He also traveled to New York City to attend a conference by Marcus Garvey. When he returned to France, the French government saw him as a troublemaker. His newspaper closed, and his organization stopped. He had to leave France and move back to Dahomey. Later, he moved to Dakar, Senegal. French authorities continued to bother him there. He died in 1936 from typhoid fever while in prison.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Marc Tovalou Quénum, later known as Kojo Tovalou Houénou, was born on April 25, 1887. His birthplace was Porto-Novo. At that time, Porto-Novo was a French protectorate. It was a key area in the wars between the French colonial empire and the Kingdom of Dahomey.

His father, Joseph Tovalou Quénum, was a successful businessman. His mother was the sister of Béhanzin, the last independent king of Dahomey. Joseph supported the French empire. He believed it would help the region's economy. He even helped the French during the First Franco-Dahomean War. For his service, he received a French medal of honor. He also became an advisor to the French colonial government.

In 1900, Joseph took Kojo and his half-brother to Paris. They visited the World's Fair. While there, Joseph decided to enroll Kojo in a boarding school in Bordeaux. Kojo finished school and earned a law degree in 1911. He also had some medical training. In August 1914, he volunteered to be an army doctor for France in World War I. He was injured in 1915 and left the military. He then moved to Paris with a military pension.

Life in Paris and Dahomey

Lime: Rest of French West Africa

Dark gray: Other French possessions

Darkest gray: French Republic

In 1915, Kojo Tovalou Houénou became a French citizen. This was very rare for people of African descent in colonial Africa. By 1920, fewer than 100 Africans had French citizenship. By 1918, he became a lawyer. He also became a minor celebrity in Paris. French newspapers even wrote about his relationships with famous people. Kojo became involved in the intellectual scene in Paris. He tried to share his ideas with the public. In 1921, he published a scientific study about language.

In late 1921, Kojo returned to Dahomey. It was his first visit since he left for school in 1900. His father had lost his position as an advisor in 1903. The French authorities wanted to limit his father's influence. Kojo saw the poverty in the colony. After riots in Porto-Novo in 1923, he became more critical of the French government. At first, he only wanted to change how France managed its colonies. He did not want to end French rule completely. He formed an organization called Amitié franco-dahoméenne in 1923. Its goal was to slowly reform the French colonial government.

With his new focus, he changed his last name from Quénum to Houénou. He also started using his traditional name, Kojo, instead of Marc. He even claimed the royal title of Prince. While he was the nephew of Béhanzin, the last independent king of Dahomey, his claim to be a Prince was questioned by some.

After returning to France in 1923, Kojo was involved in a big incident about race in Paris. He was at the El Garòn nightclub in Montmartre. Americans there attacked him because they were angry about an African person being in the club. The club owner then forced Kojo and another African person to leave. This caused a scandal in the French press. The French government and newspapers criticized the Americans. They said Americans were trying to bring racial segregation to France. The French press praised Kojo, calling him "a kind of colored Pascal." Before this, Kojo had only played a small role in colonial reform. But this incident seemed to change him. He began to push for African colonies to rule themselves, with equal status to France.

Activism and Challenges

After the nightclub incident, Kojo Tovalou Houénou became a strong critic of French colonial rule. He still believed Africans could fit into French society. But he now thought this could only happen if Africans had equal rights. He argued that if Africans in French colonies were not given equal citizenship, they should break away and rule themselves.

To achieve this, he started an organization in 1924. It was called the Ligue Universelle pour la Défense de la Race Noire. He also founded a newspaper called Les Continents with René Maran. They had studied together in Bordeaux. That same year, he visited the United States. He attended a meeting of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in New York City. He also visited cities like Chicago and Pittsburgh.

Kojo shared some goals with UNIA. However, he believed France was mostly fair. He thought France only needed to reform its colonial system. He did not think France needed the same big societal changes that UNIA sought in the United States. In 1924, he said at the UNIA meeting that France "will never tolerate the prejudices of color. She considers her black and yellow children the equal of her white children."

But when he returned to France, his involvement with UNIA made the French government suspicious. They began to see him as a radical. They even accused him of being a communist. The French colonial government started watching Kojo's activities. They considered Les Continents a dangerous publication. The Ligue Universelle pour la Défense de la Race Noire faced so much pressure from the French government that it closed in late 1924. Legal problems also caused Les Continents newspaper to go bankrupt, and it stopped publishing in December 1924.

After returning from the UNIA meeting in 1924, French authorities forced Kojo to leave France. He was only allowed back into Dahomey in 1925 if he rejected Marcus Garvey's ideas, which he did. Also in 1925, he lost his right to practice law. French authorities watched him closely. He was arrested many times without clear reasons. In 1925, he was blamed for unrest in Dahomey. The French authorities then forced him to leave the colony.

During another trip to the United States in 1925, Kojo was asked to leave a Chicago restaurant because of his race. When he refused, the police were called. He was forcefully removed from the restaurant. Kojo was arrested and tried to sue the police officers. The French government had to step in to resolve the situation.

Later Years and Death

In his later years, Kojo Tovalou Houénou continued to face harassment from French colonial authorities. He traveled to Dahomey and France sometimes. But he could not live permanently in either place because of the constant pressure. In 1931, he married Roberta Dodd Crawford, a singer from Texas.

He spent much of his later life in Dakar, Senegal. He was often exiled from both Dahomey and France. He continued to be a target for harassment and was arrested regularly without formal charges. He became active in Senegalese politics. He ran for election in 1928 and 1932 but did not win.

In July 1936, he was arrested in Dakar on minor charges. He died of typhoid fever while in prison.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |