Kondiaronk facts for kids

Kondiaronk (around 1649–1701), also known as Le Rat (The Rat), was an important Chief of the Wendat people. He lived in Michilimackinac, a key area in New France (which is now part of the United States). The Wendat people had moved to Michilimackinac after an attack by the Iroquois in 1649. This area is a narrow waterway between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan.

Kondiaronk was known as a brilliant speaker and a smart leader. He led his people, the Wendat (also called Huron) and Petun refugees, against their long-time enemies, the Iroquois. Kondiaronk believed the only way to keep his people safe was to make sure the Iroquois and the French kept fighting. This would keep the Iroquois busy and protect the Hurons from being wiped out.

He managed to stop a peace agreement between the French and Iroquois at one point. However, once he felt his people were secure, he worked towards a big peace agreement. This led to the famous Great Peace of Montreal in 1701. This treaty brought peace between France, the Iroquois, and many other Native American tribes around the Great Lakes. It ended the Beaver Wars and opened up North America for more French exploration and trade. Kondiaronk helped everyone see the benefits of this peace.

A Jesuit historian, Father Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, wrote that no other Native American had "greater merit, a finer mind, more valor, prudence or discernment." Louis-Hector de Callière, the French governor, said he owed the success of the peace talks to Kondiaronk. Sadly, Kondiaronk got a fever and died in Montreal on August 2, 1701, during the peace negotiations. He was buried at Montreal's Notre-Dame Church after a grand funeral. Today, his grave is no longer there. The Kondiaronk Belvedere in Montreal's Mount Royal Park is named after him. In 2001, the Canadian government recognized him as a Person of National Historic Significance.

Contents

Early Efforts for Peace

Kondiaronk first became important in 1682. He represented the Huron tribe of Michilimackinac in talks between the French governor Frontenac and the Ottawa tribe. These two tribes shared the village of Michilimackinac. Kondiaronk looked to the French for protection from the Iroquois. This was after a Seneca chief (from the Iroquois) was killed while being held prisoner in the Michilimackinac village.

After this, the Huron sent special beaded belts called wampum to the Iroquois to apologize for the murder. However, the Ottawa representative told Frontenac that the Huron had not sent any of the Ottawa's wampum belts. The Ottawa also said the Huron blamed them for the murder. Kondiaronk insisted that the Huron's actions were only to calm the Iroquois. But the Ottawa were not convinced, and French efforts to make peace between the two tribes didn't work well. Despite the problems between the Huron and Ottawa, Kondiaronk's request to the French did lead to an alliance. This alliance helped stop the Iroquois' military advances.

Kondiaronk's Clever Plan in 1688

By 1687, the French Governor General, Denonville, had taken over land belonging to the Senecas. Kondiaronk and the Hurons agreed to be allies with the French. Denonville promised that the war against the Iroquois would continue until they were completely defeated.

In 1688, Kondiaronk gathered a group of warriors. They traveled to Fort Frontenac on their way to attack Iroquois villages. While at the fort, Kondiaronk found out that Denonville had started talking about peace with the Iroquois. This was a surprise, as Denonville had promised the Hurons that the war would continue.

Kondiaronk's group went back across Lake Ontario. They waited for the Iroquois Onondaga delegation to pass through on their way to Montreal. When the Iroquois diplomats arrived, Kondiaronk and his warriors ambushed them. One chief was killed, and the rest of the Iroquois were captured.

The prisoners explained to Kondiaronk that they were a peaceful group, not a war party. Kondiaronk pretended to be shocked, then angry, about Denonville's "betrayal." He told the Iroquois captives, "Go, my brothers, I release you. It is the governor of the French who has made me do this. I will never forgive myself if your Five Nations do not get their revenge."

Kondiaronk's group returned to their village with an Iroquois captive. This captive was meant to replace a Huron killed in the fight. When the prisoner was shown to the French commander at Michilimackinac, the commander ordered him killed. The commander didn't know his government was trying to make peace with the Iroquois. He was just following the Huron's declaration of war.

An old Seneca slave was made to watch the killing of his countryman. Afterward, Kondiaronk told the slave to go to the Iroquois. He was to report how badly the French had treated the captive. The Iroquois were angered by this, as the captive was meant to be adopted into the Michilimackinac village. They felt the French had disrespected their traditions. Because of Kondiaronk's clever actions, the peace talks between the French and Iroquois stopped. This was exactly what the Hurons wanted.

Years of Conflict and Diplomacy (1689–1701)

Starting in 1689, a decade of fighting began, known as Frontenac's War. This war involved conflicts between the French and the English. Because of Kondiaronk's smart actions, the war also included fighting between the French and the Iroquois. However, the years from 1697 to 1701 marked the start of intense diplomatic efforts. These efforts would lead to the Great Peace of Montreal four years later.

Kondiaronk was seen as responsible for making the Iroquois so angry that it was impossible to calm them. For example, the Iroquois attacked Lachine in the summer of 1689. They burned, killed, and destroyed farms, leaving the Island of Montreal in great distress. Still, Kondiaronk continued to prevent a separate French-Iroquois peace. He did this by any means possible, despite the Iroquois' aggressive actions.

In 1697, the Hurons were divided. One group, led by Kondiaronk, supported the French. Another group supported the Iroquois. Kondiaronk warned the Miamis of an upcoming attack by Lahontan and his Iroquois allies. Kondiaronk led 150 warriors in a two-hour canoe battle on Lake Erie. They defeated a group of 60 Iroquois. This victory brought Kondiaronk back to a leading position. It also restored the Hurons' place as important allies to Frontenac.

When the conflict in Europe ended with the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697, New York and New France agreed to stop fighting. New York encouraged the Iroquois to make peace with New France. Since the Iroquois could no longer use the English military threat against New France, they signed a peace treaty with Frontenac in September 1700. This was the first step in the negotiations. Kondiaronk returned to Michilimackinac and urged all the nations of the Lakes to come to Montreal the following August. He was a key planner for the peace of 1701.

The Great Peace of Montreal (1701)

The final big meeting of Native American tribes began on July 21, 1701. The main goal was to agree on a peace treaty among the tribes and with the French. One big problem was the return of prisoners. Many people had been captured during past wars and either enslaved or adopted into new families. For Governor Hector de Callière, this meeting was the result of 20 years of diplomacy.

Many groups arrived for the meeting. The first group included nearly 200 Iroquois, led by ambassadors from the Onondagas, Oneidas, and Cayugas. The Senecas and Mohawks would arrive later. They were greeted with gunshots as a salute, which was returned by the Mission Indians. They then went to the main council lodge to smoke together peacefully. That evening, a special ritual called "requickening" took place. This ritual involved wiping away tears, clearing ears, and opening throats. It was meant to prepare everyone to begin the talks the next day with the French governor, Onontio.

The next morning, the Iroquois arrived in Montreal and were greeted by the sound of cannons. Soon after, hundreds of canoes carrying French allies appeared. These included Chippewas, Ottawas, Potawatomis, Hurons, Miamis, Winnebagos, Menominees, Sauks, Foxes, and Mascoutens. In total, over 700 Native Americans were welcomed with grand ceremonies. The Calumet Dance was performed, which was special to the Far Indians. This dance helped create friendship and a feeling of cooperation.

By July 25, talks between the tribes and the French were in full swing. Kondiaronk spoke about the difficulties of getting Iroquois prisoners back from the allies. He was suspicious about whether the Iroquois would truly return their prisoners. He worried the allies would be tricked. Yet, they were so determined to make peace that they were willing to leave their prisoners to show their good faith.

The next day, Kondiaronk's suspicions were confirmed. The Iroquois admitted they did not have all the prisoners they had promised to return. They explained that the prisoners, as small children, had been given to families for adoption. They said they were not in control of their young people. This explanation annoyed the Hurons and Miamis. They had forced their Iroquois captives away from foster families to return them. The following days were filled with deep discussions and arguments. Kondiaronk, who had convinced his own and allied tribes to bring their Iroquois prisoners to Montreal, was angry and embarrassed. He returned to his hut that night, preparing to speak strongly the next day about the importance of cooperation.

Kondiaronk's Last Speech and Legacy

During the discussions on the last day of July, Kondiaronk became ill. He was too weak to stand at the conference on August 1. He sat in a comfortable armchair. After drinking an herbal syrup, he felt strong enough to speak. For the next two hours, he criticized the Iroquois for their behavior. He also talked about his role in preventing conflict with the Iroquois. He spoke of his success in getting prisoners back and his part in the peace talks. La Potherie, who wrote about these events, said, "We could not help but be touched by the eloquence with which he expressed himself." He added that everyone recognized Kondiaronk as "a man of worth." Kondiaronk returned to his hut after speaking, too tired to stay at the conference. He died at 2 a.m. the next day, at the age of 52. It was because of Kondiaronk's inspiring speeches that the remaining groups were convinced to sign the peace treaty, the Great Peace of Montreal.

When his death was announced, many Iroquois, known for their burial ceremonies, took part in a ritual called "covering the dead". Sixty men marched in a procession. They sat in a circle around Kondiaronk's body. A chanter sang for a while. Then, another speaker wiped away the mourners' tears and offered comforting words. He then restored the "Sun" and urged the warriors to move from darkness to the light of peace. Afterward, he covered the body. Kondiaronk was later buried in a Christian ceremony at Notre-Dame Church in Montreal.

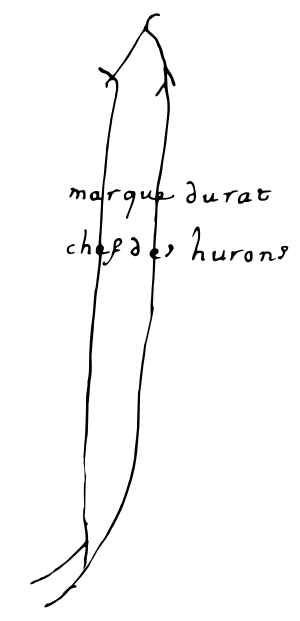

His funeral was grand, with both Native Americans and French people taking part. French representatives walked with groups from the Huron and Petun tribes. In front of the coffin marched a French officer, soldiers, Huron warriors, and French clergymen. Six war leaders carried the coffin, which was covered with flowers. On top of the coffin were a gorget (a piece of armor), a sword, and a plumed hat. Behind the coffin followed Kondiaronk's relatives, along with Ottawa and Huron-Petun chiefs. Important French officials were at the back of the procession. At the grave, the war leaders fired a salute. The inscription on his resting place read: Cy git le Rat, Chef des Hurons ("Here lies the Muskrat, Chief of the Hurons"). Today, there is no trace of this burial place, but it is thought to be near the Place d'Armes.

The French admired Kondiaronk. They used him as an example of what all chiefs should be like. They compared him to French leaders, seeing him as a model for chiefs who would lead with agreement and gentle authority. The French imagined these chiefs as leaders of small areas, working with the French government. This idea caused some tension between Native Americans and France until French Canada fell in the mid-1700s. Kondiaronk was remembered in books, appearing as "Adario" in the Baron de Lahontan's New Voyages to North America (1703). Because of this, he became the example for all "noble natives" written about in European literature.

Kondiaronk's Powerful Speeches

In their book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, anthropologists David Graeber and archaeologists David Wengrow discuss the writings of French explorer and philosopher the Baron Louis-Armand Lahontan. His journals, New Voyages to North America, were published in the early 1700s. Graeber and Wengrow describe Lahontan's interviews with Kondiaronk, who is given the made-up name Adario in the book.

In many Native American societies, people avoided strict hierarchies. Instead, they used persuasion to make public decisions. Being a good speaker was a highly valued skill. Kondiaronk's speaking skills were said to be unmatched. His abilities earned him visits to fancy homes in Paris and regular debates with the Governor of Montreal, Hector de Callière. One of these debates, in 1699, was witnessed by Lahontan. Graeber and Wengrow retell it:

Kondiaronk: I have spent 6 years thinking about European society. I still can’t find a single way you act that isn't unkind. I think this is because you stick to your ideas of "mine" and "thine." I say that what you call "money" is the worst evil, the ruler of the French, the cause of all bad things. It destroys souls and kills the living. To think you can live in the land of money and keep your soul is like thinking you can live at the bottom of a lake. Money causes luxury, bad desires, tricks, lies, betrayal, and dishonesty—all the world’s worst behavior. Fathers sell their children, husbands their wives, wives betray their husbands, brothers kill each other, friends are false—all because of money. Knowing all this, tell me that we Wyandotte are not right to refuse to touch or even look at silver.

Do you really think I would be happy to live like someone in Paris? To take two hours every morning just to get dressed? To bow and scrape before every rude person I meet who just happened to be born rich? Do you really think I could carry a purse full of coins and not immediately give them to hungry people? That I would carry a sword but not immediately use it on the first group of thugs I see forcing poor people into the Navy? If, on the other hand, Europeans lived the American way, it might take time to get used to it. But in the end, you would be much happier.

Callière: Try, for once, to actually listen. Can't you see, my dear friend, that European nations could not survive without gold and silver or something similar? Without it, nobles, priests, merchants, and many others who can't work the land would simply starve. Our kings would not be kings. What soldiers would we have? Who would work for kings or anyone else?

Kondiaronk: You honestly think you'll convince me by talking about the needs of nobles, merchants, and priests? If you gave up the ideas of "mine" and "thine," yes, these differences between people would disappear. Everyone would be equal, like among the Wyandotte. And yes, for the first thirty years after getting rid of selfishness, you would see some sadness. Those who only know how to eat, drink, sleep, and have fun would suffer and die. But their children would be fit for our way of living. Again and again, I have explained the qualities we Wyandotte believe should define humanity: wisdom, reason, fairness, etc. And I have shown that having separate material interests destroys all these qualities. A person motivated by self-interest cannot be a person of reason.

Graeber and Wengrow point out that Europeans seemed to have lost the ability to imagine their culture could be different. Kondiaronk was willing to consider that Native Americans could adapt to European culture. But Callière was not willing to imagine such big changes in the opposite direction.

Graeber and Wengrow argue that dismissing the philosophical statements of indigenous people as made up by Europeans is a form of unfair bias. However, historian David A. Bell has questioned if this speech is truly authentic. He says that European writers often presented fictional stories as real-life accounts during that time.

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |