La Matanza facts for kids

Quick facts for kids La Matanza |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

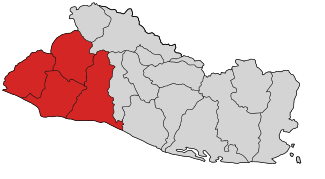

Map of the Salvadoran departments affected by the revolt. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Peasant rebels

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Between 10,000 and 40,000 dead, 20,000 dead | |||||||

On January 22, 1932, Pipil peasants and members of the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCES) started a rebellion. They were protesting against the military government of El Salvador. People were unhappy due to widespread social problems and a lack of political freedom. This was especially true after the results of the 1932 election were cancelled.

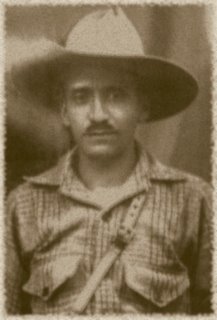

During the first part of the rebellion, indigenous and communist rebels took control of several towns in western El Salvador. Their leaders included Feliciano Ama and Farabundo Martí. About 2,000 people died, and property damage was estimated at over USD$100,000. The Salvadoran government, led by General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, quickly responded. He had taken power after a military takeover in 1931. He declared martial law and ordered the rebellion to be stopped.

What followed was a terrible event known as La Matanza (which means "The Massacre" in Spanish). Between 10,000 and 40,000 people were killed. Most of those who died were Pipil peasants and ordinary people, not fighters. Many rebel leaders, like Ama and Martí, were executed by the military. This violence also forced many thinkers and writers to leave the country.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

Social problems in El Salvador grew in the 1920s. People felt that the ruling class was unfair, and there was a huge gap between rich landowners and the poor Pipils. An American officer noted in 1931 that there was "practically no middle class." A few wealthy families, known as 'los catorce' (the fourteen), owned 90 percent of the country's land. They used this land to grow coffee, which was sold for profit.

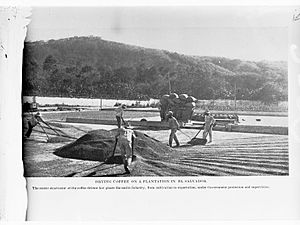

El Salvador's economy relied heavily on coffee in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This time is called the "Coffee Republic" era. A small group of landowners and merchants became very rich from coffee. They bought huge amounts of land and hired many peasants, including many indigenous people. Working conditions on these large farms, called haciendas, were very bad. By 1930, workers were paid with just two tortillas and two spoonfuls of beans each day. They were also paid with special money called scrip. This scrip could only be used at stores owned by the plantation owners. This meant owners could charge high prices for food, making even more money.

In 1932, a U.S. official in San Salvador wrote that farm animals were worth more than workers. This showed how little value was placed on human labor.

Economic Hardship and Land Loss

The Great Depression caused a global economic crisis. This led to a lack of jobs in countries like El Salvador. Coffee prices dropped, so many haciendas closed. Many peasants lost their jobs, causing great economic trouble. While the crisis affected the whole country, it was worst in western El Salvador. Presidents Pío Romero Bosque and Arturo Araujo had taken almost all land from local peasants. This area was home to many indigenous Pipils.

Indigenous people were left out of the little economic progress that existed. They turned to their own leaders, called caciques, for help. Even though the law didn't officially recognize caciques, native people respected their authority. Politicians often sought the support of caciques during elections.

To help with the crisis, the Pipil people formed cooperative groups. These groups provided jobs, often linked to Catholic festivals. The caciques led these groups and spoke for the unemployed to the authorities. Feliciano Ama was a very active cacique and was highly respected. He had even arranged for financial help from President Romero in exchange for his support.

The crisis also worsened the conflict between indigenous and non-indigenous people. Non-indigenous people usually had better connections with the government. When riots happened, indigenous leaders were often arrested and sentenced to death.

Political Instability and New Leadership

Before the rebellion, El Salvador was politically unstable. Since 1871, the country had been ruled by economic liberal leaders. These leaders had brought a long period of peace. By World War I, the presidency often switched between the Meléndez and Quiñónez families. In 1927, Pío Romero Bosque became president. He started political changes that led to what many consider El Salvador's first truly free election in 1931.

Arturo Araujo won the 1931 elections during a severe economic crisis. After a military takeover in December 1931, Vice President Maximiliano Hernández Martínez took control. This marked the start of El Salvador's military rule. Hernández Martínez's government was known for its strict laws. For example, stealing was punished by cutting off a hand. He made police forces stronger and was very harsh against anyone who rebelled. He even ordered the death penalty for those who opposed him.

Even though Hernández Martínez's rule pleased the military, people's unhappiness grew. His opponents continued to protest. Within weeks, communists believed the country was ready for a peasant rebellion. They began planning an uprising against Hernández Martínez.

Key Factors Leading to the Uprising

Many events and situations directly led to the conflict. The Salvadoran Army was ready to stop any uprisings. Peasants, both indigenous and non-indigenous, began to protest against local authorities. Finally, the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCS) became involved, which helped spark the uprising.

The Salvadoran Army's Strength

The army had different groups: infantry (foot soldiers), artillery (big guns), machine guns, and cavalry (soldiers on horseback). Their main weapon was the German-made Gewehr 98 rifle. The air force was not very important then; it mainly did scouting missions.

The army reported directly to the President. Its main goal was to protect the country. Other security forces included the National Police, the National Guard, and the Hacienda Police.

Early Peasant Protests

Because of poverty and inequality, some peasants who lost their land and had low-paying jobs began to protest. At first, these protests were individual, making it easy for authorities to stop them. Large landowners had strong ties to the military. So, official security forces protected their haciendas.

After many arrests, peasants started to organize quietly. They didn't have a clear leader, so their efforts were scattered and easily put down. Security forces arrested rebels, and many were later sentenced to death by firing squad or hanging. We don't know how many executions happened before the main massacre. However, many peasant leaders and even some public officials who helped them were punished.

The Communist Party's Role

At the same time as the conflicts between indigenous people, peasants, landowners, and authorities, the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCS) grew. They handed out flyers and gained new members. People were frustrated by broken promises from the government and other political parties. Communist leaders, led by Farabundo Martí, built a political group that gained public support. After the 1931 military takeover, the press had more freedom. This helped the PCS spread their revolutionary ideas.

The PCS ran candidates in the January 1932 elections. However, elections back then were often unfair. People had to vote publicly, which scared voters and made it hard for democracy to work.

After the elections, there were many claims of fraud. The communist leaders then decided to give up on elections and plan an uprising instead.

The uprising was planned for mid-January 1932. It even had support from some military members who sympathized with the communists. But before it could happen, police arrested Martí and other communist leaders. Authorities found documents proving the planned rebellion. These documents were used as evidence in military trials.

Even though the PCS suffered a big setback, the uprising was not cancelled. By late January 1932, the country was in chaos. Security forces arrested anyone involved in rebellious acts. Meanwhile, indigenous people in the West began to protest their poor living conditions. There is no clear proof that the peasant uprising was directly led by the PCS. However, because both uprisings happened around the same time, the armed forces treated them both as one movement.

The Uprising Begins

Late on January 22, 1932, thousands of peasants in western El Salvador rebelled against Hernández Martínez's government. They were armed with sticks, machetes, and old shotguns. Rebels led by the Communist Party and Agustín Farabundo Martí, Mario Zapata, and Alfonso Luna attacked government forces. They had strong support from the indigenous Pipil people.

Armed mostly with machetes, peasants attacked large farms and military bases. They took control of several towns, including Juayúa, Nahuizalco, Izalco, and Tlacopan. However, military bases in towns like Ahuachapán, Santa Tecla, and Sonsonate fought back and stayed under government control. It's thought that the peasant rebels killed no more than 100 people. Confirmed deaths include about twenty civilians and thirty soldiers.

Juayúa was the first city taken. There, a landowner named Emilio Radaelli was killed. Several other military leaders and government officials were also executed.

Different stories exist about what happened, and it's hard to know exactly what is true. This is because very few people survived the rebellion. Some say indigenous people attacked private property and committed crimes in towns. There is some evidence for this, but it's possible that criminals joined the uprising to cause trouble. We cannot say for sure if indigenous people and peasants were involved in looting. However, the main reason for the events is clear: poverty and unfairness.

The connection between the peasants and the Communist Party is also debated. The uprisings happened at the same time and had similar causes, suggesting they were linked. Some believe the PCS used the economic problems to convince peasants to rebel. But little is known about the exact relationship between the two groups. Some historians, like Erik Ching, say the PCS probably couldn't have led the uprising. They had little influence over peasants and faced their own internal problems.

Regardless, the government treated both movements as the same.

Government's Quick Response

The government reacted very quickly. They sent out the military to take back lost areas and stop the rebellion. With better training and weapons, government troops defeated the rebels in just a few days.

General José Tomás Calderón had many soldiers and weapons. He noted:

The use of superior armament was the decisive element in the confrontation and the stories speak of "waves of Indians, blown away by machine guns." This was followed by extreme suppression, executed by units of the Army, Police, and National Guard, as well as volunteers organized into "civil guards."

Civil guards were volunteers who helped the security forces patrol. They also fought alongside the military when needed.

On January 23, Canadian warships, the Skeena and Vancouver, arrived at the Port of Acajutla. Britain had asked for these ships to protect any British citizens in El Salvador. US ships arrived soon after. The crews of these ships were ready to help the Salvadoran government stop the rebellion. However, the chief of operations in El Salvador turned down their offer. He stated:

The chief of Operation of the Western Zone of the Republic, Major General José Tomás Calderón, presents his compliments on behalf of the government of General Martínez and of himself, to Admiral Smith and Commander Brandeur, of the Rochester, Skeena, and Vancouver, I am pleased to announce that peace in El Salvador is restored, that the communist offensive has been completely suppressed and dispersed, and that complete extermination will be achieved. 4,800 Bolsheviks were wiped out.

We don't know the exact number of deaths in the first 72 hours after the uprising. But many historians agree it was around 25,000 people. Those who were captured alive were put on trial and almost always sentenced to death.

After the rebellion, peasant leader Francisco Sánchez was executed. Feliciano Ama, another leader, was killed by a mob.

In the areas around Izalco, anyone found with a machete or who looked indigenous was accused of rebellion and found guilty. To make the security forces' job easier, people who had not rebelled were asked to come forward for documents proving their innocence. When they arrived, they were checked. Those with indigenous features were arrested. They were shot in groups of 50 in front of the town church, Iglesia de La Asunción. Some were forced to dig mass graves, into which they were thrown after being shot. The homes of those found guilty were burned, and surviving family members were shot.

The commander of the operation claimed 4,800 members of the PCS were killed. This number is hard to confirm.

After the conflict, survivors tried to escape to Guatemala. But President Jorge Ubico ordered the border closed. Anyone trying to cross was handed over to the Salvadoran army.

To end the conflict, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador passed a law on July 11, 1932. This law gave full forgiveness to anyone who committed crimes to "restore order, repress, persecute, punish and capture those accused of the crime of rebellion of this year."

The Aftermath of the Massacre

After stopping the rebellion, Hernández Martínez's government began to suppress anyone who opposed them. They used voter lists to scare or execute people who had spoken out against the government.

The killings especially targeted people who looked, dressed, or spoke like indigenous people. In the years that followed, Salvadoran indigenous people increasingly stopped wearing their traditional clothes and speaking their native languages. They did this out of fear of more attacks. These events led to the near total loss of the Pipil-speaking population. The indigenous people gave up many of their traditions because they were afraid of being arrested. Many indigenous people who did not join the uprising said they didn't understand why the government was persecuting them.

Over the years, the number of people who identify as indigenous has dropped to about 10% in the 21st century. For ten years after the uprising, the military stayed in the area. Their goal was to keep peasants under control so that such events would not happen again. After Hernández Martínez's rule ended, the way of dealing with peasant unhappiness changed. Instead of just repression, there were some social reforms that helped them, at least for a while.

In 2010, President Mauricio Funes apologized to the indigenous communities of El Salvador. He apologized for the brutal acts of persecution and extermination by past governments. He made this statement during the first Congress of Indigenous Peoples. He said, "My government wishes to be the first government to, on behalf of the State of El Salvador, of the people of El Salvador, and of the families of El Salvador, make an act of contrition and apologize to the indigenous communities for the persecution and extermination of which they were victims during so many years."

Remembering the Events

In the town of Izalco, the uprising is remembered every January 22. While not widely covered by national media, local authorities support the event. They honor all those who were killed. Speakers include people who lived through the event and relatives of Feliciano Ama.

See also

In Spanish: Levantamiento campesino en El Salvador de 1932 para niños

In Spanish: Levantamiento campesino en El Salvador de 1932 para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |