Lafayette M. Hershaw facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lafayette McKeene Hershaw

|

|

|---|---|

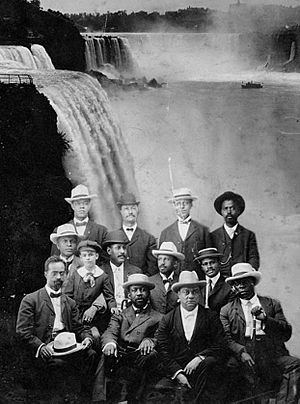

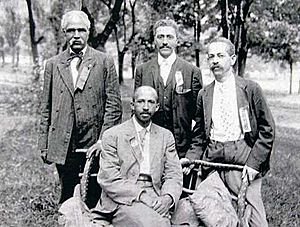

Leaders of the Niagara Movement: W. E. B. Du Bois (sitting), and (left to right) J. R. Clifford, Lafayette M. Hershaw, and F. H. M. Murray at Harpers Ferry.

|

|

| Born | May 10, 1863 |

| Died | September 2, 1945 (aged 82) Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Clark Atlanta University Howard University |

| Occupation | Journalist, Lawyer, Clerk |

| Spouse(s) | Charlotte Monroe |

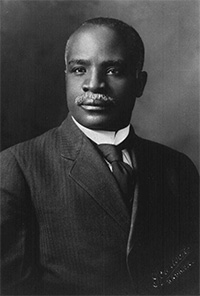

Lafayette M. Hershaw (born May 10, 1863 – died September 2, 1945) was an important American journalist, lawyer, and government worker. He worked for the General Land Office in the United States Department of the Interior.

Hershaw was a key thinker and leader among African Americans. He was active in Atlanta in the 1880s and later in Washington, D.C.. He led important social groups like the Bethel Literary and Historical Society. He strongly supported W. E. B. Du Bois. Hershaw was one of the thirteen people who started the Niagara Movement. This group was a major step before the creation of the NAACP. He also helped found the Robert H. Terrell Law School and served as its president.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lafayette McKeene Hershaw was born on May 10, 1863. His birthplace was Clay County, North Carolina. His parents were Abraham Hershaw and Anne McKeene. He learned to speak and read French, Spanish, and German.

Hershaw started studying at Atlanta University in 1879. He earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1886. He then studied law at Howard University. He received a law degree from Howard in 1892.

On July 11, 1888, he married Charlotte Monroe. They had three daughters: Rosa Cecile, Alice May, and Fay M. Charlotte died on October 26, 1930.

Hershaw passed away on September 2, 1945, in Washington D.C. His funeral was at the Plymouth Congregational Church. He was buried in Lincoln Memorial Cemetery.

Working in Atlanta Schools

Hershaw's public service career began in Atlanta. He worked as a teacher and principal at the Gate City School. This school was part of the Atlanta Public School District. He worked there from 1886 to 1889.

At that time, Atlanta University had both white and black teachers and students. In 1889, a law called the Glenn Bill was proposed. This bill would force all schools to be separated by race. It would also create special schools for African Americans. Hershaw spoke out strongly against this bill.

In July 1889, Hershaw gave a speech. He said that education was better in the North than in the South. This speech upset some members of the Atlanta Board of Education. They had Hershaw fired from his job.

Government Work in Washington, D.C.

In 1890, Hershaw moved to Washington, D.C. He started working for the United States federal civil service. He became a land examiner in the United States Department of the Interior. He worked there for 42 years.

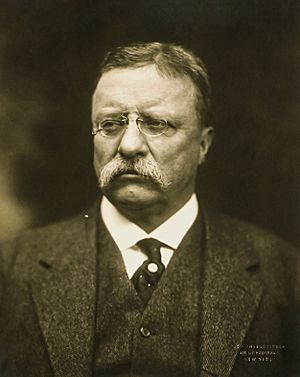

Some believed his job was due to Theodore Roosevelt's view. Roosevelt, then a Civil Service Commissioner, said that race should not stop someone from getting a job. Hershaw supported President Roosevelt and the Republican Party. He believed Roosevelt stood for fairness and equality.

Later, some people tried to get Hershaw demoted. This was because he was seen as opposing Booker T. Washington and Roosevelt in the black press. However, Hershaw kept his job. In 1925, he was promoted to Assistant Law Examiner. This was the highest position held by a black man in the Land Office at that time.

Early Views on Civil Rights

In 1895, Booker T. Washington gave a famous speech. It was called the Atlanta Exposition Speech. This speech suggested a compromise for black people in the South. It offered education and fair treatment in exchange for white political control.

In Washington, D.C., many groups discussed this speech. Hershaw supported Washington's ideas at first. He called the speech "logical, instructive, and sensible." He liked the part that asked for harmony between races.

In 1898, Kelly Miller gave a speech at Howard University. He spoke about the progress of black people. Hershaw defended Miller's ideas in a newspaper. He said that African Americans had made great contributions.

Joining Activist Groups

After moving to Washington, D.C., Hershaw became part of the city's intellectual leaders.

Bethel Literary and Historical Society

In 1892, Hershaw spoke at the Bethel Literary and Historical Society. He became a regular member. In 1897, he was elected president of the society. He helped the group support calls for civil service reform. He also spoke out against lynching, supporting activists like Ida B. Wells.

Pen and Pencil Club

In 1899, black journalists and writers formed the Pen and Pencil Club. Hershaw was the president of this club in 1901. The club celebrated important figures like Frederick Douglass.

In 1903, Hershaw gave a speech at the Second Baptist Lyceum. He quoted W. E. B. Du Bois's famous line: "the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line." Hershaw's speech supported Du Bois's ideas. He spoke about the equality of blacks and whites. He also stressed the importance of political and civil equality.

Working with W. E. B. Du Bois

Hershaw often gave speeches about the history and challenges of black people. In 1905, he went to the Tenth Atlanta Conference. This conference was organized by W. E. B. Du Bois. Hershaw gave a speech written by Du Bois called "Address to the Country." It was very well received.

Niagara Movement

Less than two months later, Hershaw attended the first meeting of the Niagara Movement. This meeting was called by Du Bois in Buffalo, New York. Hershaw was one of the 29 African Americans who attended. By December, Hershaw was the secretary of the movement.

The second meeting of the movement was held at Harper's Ferry. This was to honor John Brown. Hershaw gave a strong speech there. He urged people to take political action. The Niagara Movement was against the compromise ideas of Booker T. Washington. Hershaw sided with Du Bois in this disagreement.

The Horizon Magazine

To share their views, Du Bois, Hershaw, and F. H. M. Murray started a magazine called The Horizon. It was published from 1907 to 1910. Du Bois and Hershaw were co-editors. Hershaw often wrote a column called "The Out-Look." This column looked at the black experience from a white perspective. Hershaw also supported women's rights and voting rights for black women.

Joining the NAACP

As the Niagara Movement declined, a new group was formed. In 1909, the National Negro Committee was created. Hershaw was a member of this committee. This led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The Washington, D.C., branch of the NAACP was very strong. Hershaw was one of its early and important members.

In 1911, Hershaw and other NAACP members met with President Taft. They asked him to take action against lynching. However, Taft refused their request.

Work with the D.C. Branch

In 1912, Archibald Grimké helped organize the D.C. branch of the NAACP. Hershaw became an officer. One of their first goals was to end racial segregation in the federal government. Hershaw helped collect information to show how widespread segregation was.

In 1918, Hershaw was chairman of the D.C. Branch Executive Committee. He worked to support Sergeant Edgar Caldwell. Caldwell had shot a white man in self-defense. Despite their efforts, Caldwell was executed in 1920.

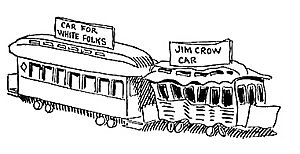

In 1919, Hershaw worked to pass a law to end "Jim Crow" cars. These were segregated train cars. The proposed law, called the Madden Amendment, did not pass.

In 1928, Hershaw resigned from the D.C. branch. He did not want to support a fight against segregation in the Interior Department. He still worked there and felt that conditions were acceptable for him and other black clerks.

Robert H. Terrell Law School

Hershaw passed the bar exam to become a lawyer. However, he did not practice law much. In 1931, he helped found the Robert H. Terrell Law School. This school was named after his colleague, Robert H. Terrell. Hershaw taught at the school and was its president in the mid-1930s. The school closed in 1950.

Other Activities

Hershaw was a member of many groups. He was a trustee of Atlanta University. He was president of the Bethel Historical and Literary Association in 1897. He also spoke at other groups like the Second Baptist Lyceum. In 1907, he led the newspaper bureau of the National Afro-American Council. He was also president of the Crispus Attucks Association in 1909.

In the 1910s, Hershaw became more involved with the American Negro Academy. He was on its executive committee. He also served as treasurer in 1920 and 1921. In 1917, he was vice president of the Mu-So-Lit club. This club was for musical, social, and literary professionals in D.C.

Images for kids

-

Booker T. Washington, 1903 portrait

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |