Libby Prison escape facts for kids

The Libby Prison escape was a daring prison escape during the American Civil War. In February 1864, over 100 Union soldiers, who were prisoners of war, broke out of Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. This event became one of the most successful prison breaks of the entire war.

The escape was led by Colonel Thomas E. Rose of the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry. The prisoners dug a secret tunnel from a part of the prison that was full of rats. Confederate guards usually avoided this area. The tunnel ended in an empty lot next to a warehouse. From there, the escapees could walk out without being noticed. Because the prison was thought to be impossible to escape from, the guards were not as watchful. The alarm was not raised for almost 12 hours. More than half of the prisoners made it safely to Union lines. Many knew the area well from fighting in McClellan's Peninsula Campaign in 1862.

Contents

What Was Libby Prison?

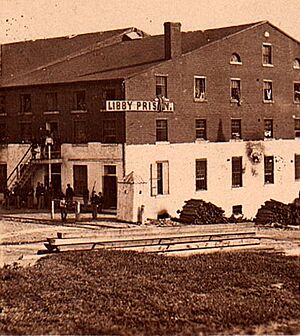

When the Civil War began, a man named Luther Libby ran a ship supply store in a big warehouse in Richmond, Virginia. The Confederate soldiers needed a new prison for captured Union officers. So, they told Libby to leave his property within 48 hours. The sign that said "L. Libby & Son, Ship Chandlers" was never taken down. This is how the building and the prison got its name. The Confederates believed no one could escape from this building. Because of this, the guards thought their job would be easy.

Prison Layout and the Secret Tunnel

Libby Prison took up a whole city block in Richmond. To the north was Cary Street, which connected the prison to the rest of the city. To the south was the James River. The prison building itself had three floors above ground. It also had a basement that was open on the river side. Confederate soldiers painted the outside walls white. This was to make any prisoners trying to sneak around easy to spot.

The first floor of Libby Prison held the offices for the Confederate guards. The second and third floors were used to hold the prisoners. The basement of the prison was split into three parts. The west end was a storage room. The middle part was a carpenter's shop used by civilians. The east end was an old, unused kitchen. This kitchen area was once used by Union prisoners. However, it became filled with rats and often flooded. Because of this, the Confederates closed it off. This abandoned area became known as "Rat Hell."

Exploring "Rat Hell"

Most prisoners and guards tried to stay away from "Rat Hell." But a few Union officers secretly planned to get into it. They removed a stove on the first floor and chipped away at the chimney next to it. This created a small, tight passage to reach the eastern basement. Once they could get between the two floors, the officers started planning how to dig their way out.

The floor of "Rat Hell" was covered with two feet of straw. This straw was both a problem and a help for the officers. On one hand, it was a perfect place to hide the dirt dug from the tunnel. Captain I. N. Johnston, who spent a lot of time in "Rat Hell," explained how they hid the dirt. They made a wide, deep hole in the floor. They packed the loose dirt tightly into it and then covered it with straw. This way, the Union officers could hide all signs of the tunnel. This kept civilians and wandering guards from finding out. The straw also offered a good hiding spot for the workers during the day.

One man was chosen to hide all signs of the tunnel. He would do this while the digging team climbed back to the first floor. He would then stay buried in the straw for the rest of the day. Another team would arrive at dusk to take his place. Johnston wrote that without the large amount of straw, their plan would have been discovered almost as soon as it started. Even though the straw was helpful, it was also why the area was called "Rat Hell." Lieutenant Charles H. Moran, an officer who was recaptured from Libby, described the terrible conditions. He said no words could explain how the men endured the squealing rats, the sickening air, the cold, and the endless darkness.

Major A. G. Hamilton, a main planner of the escape, talked about the problem with the rats. He said the only difficulties were not having good tools and hearing hundreds of rats squeal all the time. The rats would even run over the diggers without fear. Colonel Thomas E. Rose, the leader of the escape, also mentioned the lack of light in "Rat Hell." He said the deep darkness made some men confused when they tried to move around. He sometimes had to feel his way around the cellar to find the lost men. Despite these problems, the dark and unpleasant atmosphere of "Rat Hell" offered the best cover for their secret work. Guards rarely entered these large basement rooms. It was such an unwelcoming place that Confederates made their visits as short as possible.

The Element of Surprise

The tunnel diggers were organized into three teams, with five members each. After 17 days of digging, they finally broke through. The tunnel led to an empty lot about 50 feet from the prison. They came out under a tobacco shed inside the grounds of a nearby place called Kerr's Warehouse. When Colonel Rose finally broke through, he told his men that the "Underground Railroad to God's Country was open!" The officers escaped the prison in groups of two and three on the night of February 9, 1864. Once inside the tobacco shed, the men gathered in the walled warehouse yard. Then, they simply walked out the front gate.

It might seem risky for Union officers to walk through the streets of Richmond late at night. However, the guards simply did not expect anyone to escape from Libby Prison. Because the Libby guards were not looking for signs of an escape, they were easier to fool. Union Army Lieutenant Moran explained that the guards were not interested in stopping people outside their specific patrol areas. This was true as long as the person was not recognized as a "Yankee." The tunnel created enough distance from the prison. This allowed prisoners to quietly cross those patrol lines and slip into the dark streets without being challenged.

This clever plan worked so well that 109 men escaped the prison without ever being stopped. At one point, Colonel Rose walked directly into the path of an oncoming guard. Without flinching, he "strode boldly past the guard unchallenged." Even more amazing, once news of the escape spread among the prisoners, a panicked rush began. This created a loud stampede for the tunnel. One Confederate guard, completely unaware of what was happening, yelled to a fellow guard, "Halloa, Bill—there's somebody's coffeepot upset, sure!"

Precious Time Gained

Another example of how surprised the Confederates were is seen in their reaction to the escape. The Richmond Examiner newspaper reported on February 11, 1864, that at first, they suspected the night guards had been bribed. The guards were arrested, searched for proof, and put in Castle Thunder, a civilian prison near Libby. But when the tunnel was discovered, the imprisoned guards were immediately released and put back on duty.

Even with the stampede of prisoners, strong senior officers like Colonel Harrison Carroll Hobart had the good sense to stop the flow of escapees before dawn. The remaining prisoners put the bricks back at the fireplace. The guards then started their morning routine. They did not know that 109 escaped Union officers were heading toward the Federal lines. Keeping the escape a secret from the Confederate guards for as long as possible gave the escaping prisoners what they needed most: time. After the morning roll call was over a hundred men short, the Confederates counted frantically several more times. They wanted to make sure the Yankees were not playing a trick. Such "tricks" had happened many times when men slipped in and out of the counting lines. This "repeating" was a small prank often used to annoy the Confederates during roll call, which the Union prisoners found funny.

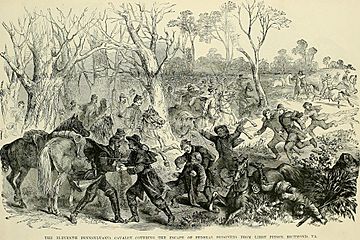

On the morning of February 10, the Confederates realized this was no trick. By this time, the first prisoners had been free for nearly twelve hours. Panic broke out among the Confederates. Messengers and dispatches were quickly sent in all directions. All the horse, foot, and dragoons (soldiers on horseback) of Richmond were chasing the escapees before noon. Despite Richmond's quick response, almost 17 hours passed before the Confederates could truly react. This delay greatly increased the chance for 59 men to reach Union lines. The Richmond Enquirer newspaper on February 11, 1864, wrote that it was feared the escapees had too much of a head start for all of them to be recaptured. Of the 109 escapees, 48 were caught again, and 2 drowned in the nearby James River.

Knowing the Land

Even though Union Commander George B. McClellan mostly faced defeat in the Peninsular Campaign of 1862, his men gained something important. For those who would later escape from Libby Prison, the time spent studying maps and walking through Virginia made them familiar with the enemy's land. This knowledge was a huge help for the prisoners making their way back to Union lines two years later. The Richmond Enquirer reported that it was believed all the fugitives headed toward the Peninsula. Lieutenant Moran, who escaped late at night, wrote that he had served with McClellan in the Peninsula campaign of 1862. He knew the country well from looking at war maps, and the friendly North Star helped him find his way.

Just as enslaved people had followed the North Star to freedom, it also guided escaped Union prisoners from Libby in 1864. Most of the prisoners mentioned following the North Star. For example, Captain Johnston wrote that he started due north, using the North Star as his guide. He only changed his direction when he came near any Rebel camps.

The Escape Leaders

Colonel Rose and Major Hamilton led the escape efforts. Rose, who was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, arrived at the prison on October 1, 1863. From the moment he got there, he was determined to escape. While exploring the dark parts of "Rat Hell," he met Hamilton, who was also looking for a good place to tunnel. They quickly became friends and worked together for the successful escape in February. At the time, Libby prisoners praised Rose and gave him credit for the escape's success.

Rose and Hamilton worked very hard together to make the escape happen. Rose thought of breaking into the basement from the chimney. Hamilton designed the passage. Rose worked tirelessly in the tunnel and organized the digging teams. Hamilton handled the plans and invented tools for removing dirt and getting air into the tunnel. Various problems made the tunneling difficult. But as Lieutenant Moran wrote, the brave Rose, helped by Hamilton, always convinced the men to try again. Soon, their knives and small saws were working with energy once more. Lieutenant Colonel Federico Fernández Cavada, a prisoner at Libby, wrote that Colonel Rose deserved most of the credit for the escape. He was very determined, never gave up, and had great engineering skills. He organized the working parties and led them every night in the prison cellars. Hamilton said that Rose was the recognized leader and planner of the tunnel. He added that it was thanks to Rose's good sense, energy, and management that the escape was a success.

Despite all his work in planning the escape, Rose was captured before reaching Union lines. He was just minutes away from a Union front at Williamsburg, Virginia. Confederate guards ambushed him and took him back to Libby Prison. Even though he was put in solitary confinement, the Confederates felt Rose's presence at Libby was now a danger. They were happy to trade the famous escape artist for a Confederate colonel on April 30, 1864. Rose returned to his unit, the 77th Pennsylvania Infantry, and fought until the end of the war.

Impact of the Escape

Judging the success of the Libby Prison escape only by the number of men who reached Union lines would be a mistake. Richmond was greatly affected by the break. Libby Prison itself was thrown into confusion, which made the remaining prisoners very happy and boosted their spirits. Lieutenant Colonel Cavada wrote about some of the funnier effects of the escape inside the prison. Once, the entire camp was woken up in the middle of the night for a roll call. A guard thought he saw something down in a sewer. It turned out to be his own shadow. Even the Confederate warden, Major Thomas P. Turner, was clearly shaken. Cavada joked that when their worried little Commandant came into their rooms, he kept his knees tightly together. He said it was necessary to be very careful, as some prisoners might slip out between his legs!

In Popular Culture

A dramatic play about the escape, called A Fair Rebel, was shown in New York City in August 1891. In 1914, a silent film version was released. It starred Linda Arvidson, Charles Perley, and Dorothy Gish, and was directed by Frank Powell.

Episode Number 25 of The Great Adventure (American TV series) also shows a dramatization of the Libby Prison escape.

Images for kids