Little England beyond Wales facts for kids

Little England beyond Wales is a special name for an area in southern Pembrokeshire and southwestern Carmarthenshire in Wales. For many centuries, people here have spoken English and followed English customs, even though they are far from England. This unique culture might have started because of settlers from Ireland, Norway, Normandy, Flanders, and Saxony who came to this area more than other parts of South West Wales. The northern edge of this area is called the Landsker Line.

Many writers and experts, both old and new, have wondered how and why this English-speaking area came to be, and why it has stayed that way for so long. There isn't one clear answer.

Contents

What Does the Name Mean?

The border between this English-speaking region and the Welsh-speaking area to the north is very clear and strong. It's often called the Landsker Line. We think this border is very old. The first time someone used a name similar to "Little England beyond Wales" was in the 1500s. A writer named William Camden called the area Anglia Transwalliana, which means "England beyond Wales."

A Look at History

Between 350 and 400 AD, an Irish tribe called the Déisi settled in this region. They mixed with the local Welsh people. This area became known as Dyfed (from 410–920), which was an independent small kingdom. Later, it became part of the kingdom of Deheubarth (920–1197). We don't know exactly when this area started to be different from other parts of Wales.

Vikings raided Wales in the 800s and 900s. Some might have settled here, just like they did further north in Gwynedd. You can find a few Scandinavian place names in the area, especially near the River Cleddau. Old Welsh stories mention battles in southwest Wales against people who might have been Saxons. The Saxons also influenced the language. In 1387, John Trevisa wrote:

Both the Flemynges that woneth in the west side of Wales. Nabbeth y left here strange speech, and speketh Saxon lych y now.

This means the Flemish people living in West Wales spoke a language similar to Saxon (English).

The Norman Period

We know that Flemish settlers came to Wales from England. A writer named William of Malmesbury (who lived from 1095 to 1143) wrote that King Henry I moved many Flemings from England to Wales. He did this to reduce the number of Flemings in England and to help control the Welsh. He settled them in a Welsh area called Ros. Because these Flemings came from England and their language was similar to English, it helped English become the main language in the area.

Another writer, Caradoc of Llancarfan (around 1135), explained more. He said that in 1108, a big flood in Flanders (now part of Belgium) forced many Flemings to find new homes. King Henry gave them land in Ros, where towns like Pembroke and Tenby are today. Caradoc noted that their speech and way of life were very different from the rest of the Welsh people.

Around 1113, King Henry sent more Flemings to southwest Wales. According to the Welsh chronicle Brut y Tywysogion, the King told his leaders to welcome the Flemings and help them live there. In return, the Flemings had to fight for the King. They settled in Rhos and Penfro. The King also placed English people among them to teach them the English language. The chronicle says these Flemings became English and were known for being tricky.

Because of this, the original Flemish language did not last in the local area. By 1327, Ranulf Higdon said Flemish was no longer spoken in southwest Wales. In 1603, George Owen also confirmed that Flemish had died out a long time ago.

After the Normans

In 1155, King Henry II sent a third group of Flemings to the Welsh lands of Rhys ap Gruffydd.

Writers like Gerald of Wales (around 1146-1223) and Brut y Tywysogyon recorded that Flemings settled in south Pembrokeshire after the Norman invasion of Wales in the early 1100s. Gerald said this happened specifically in Roose. The Flemish people were skilled at building castles, and many were built in Norman Pembrokeshire. The original people were said to have "lost their land," which could mean they were removed or that their land-owning leaders were replaced. The town of Haverfordwest grew as a castle town controlling Roose during this time. The Normans took military control of all of southwest Wales, building castles as far north as Cardigan.

After this, starting with King Edward I in the late 1200s, there was about 100 years of peace, especially in "Little England." The English crown took more control over the Welsh. This likely made Welsh less common in the region. When Owain Glyndŵr's fight for Welsh independence failed in the early 1400s, no fighting happened in "Little England." Strict laws were then put in place for Wales, but for some reason, they were not as harsh here as elsewhere.

The unique nature of the region became well known in the 1400s with the birth of Henry Tudor at Pembroke Castle. He later became King of England after starting his campaign in southwest Wales. At the end of the Tudor period, George Owen wrote his Description of Penbrokshire in 1603. This book looked at the languages spoken in the county. His writings are very important for understanding the area. He was the first to point out how sharp the language border was. He wrote:

...yet do these two nations keep each from dealings with the other, as mere strangers, so that the meaner sort of people will not, or do not usually, join together in marriage, although they be in one hundred (and sometimes in the same parish), nor commerce nor buy but in open fairs, so that you shall find in one parish a pathway parting the Welsh and English, and the one side speak all English, the other all Welsh, and differing in tilling and in measuring of their land, and divers other matters.

Owen also said about Little England:

(They) keep their language among themselves without receiving the Welsh speech or learning any part thereof, and hold themselves so close to the same that to this day they wonder at a Welshman coming among them, the one neighbour saying to the other "Look there goeth a Welshman".

Owen described the language border in detail. His 1603 map shows this line. He noted that some northern parts had started to have more Welsh speakers again. This might have happened after the problems caused by the Black Death.

Modern Times

Many writers after Owen also described Little England, mostly by quoting him. Richard Fenton noticed in 1810 that churches in the south of the county often had tall spires, unlike those in the north. More detailed studies of the language geography began around 1870 with Ernst Georg Ravenstein. His work showed that the border had shrunk a bit since Owen's time. Since 1891, the Welsh census has recorded who speaks Welsh. The overall picture is that the border has moved a little, but it is still very clear. In 1972, Brian John said the language border "is a cultural feature of surprising tenacity." He felt it was almost as strong as it was four centuries ago.

In 1976, people from Marloes in Pembrokeshire gave a talk at the British Library. Their English accent and words were very similar to those spoken in the West Country of England, not like the English spoken in southeast Wales.

Before the vote in 1997 that created the National Assembly for Wales (now called the Senedd), it was thought that Pembrokeshire's vote would be very important.

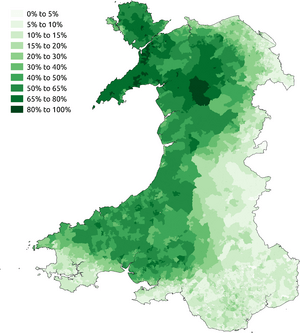

The differences in how many people speak Welsh are still clear, as shown by the map from the 2011 census. The name "Little England beyond Wales" is still used today. In 2015, Tenby was called "traditionally the heart of Little England beyond Wales."

In 2022, an ice cream company called Upton Farm, based in Pembroke Dock, was criticized for using the phrase "Made for you in little England beyond Wales" on their packaging. The company agreed to remove this phrase and instead use words that celebrate their Welsh identity.

General Information

When we look at place names, most of the Anglo-Saxon names are in the old hundred of Roose. There are also many Welsh placenames in other parts of Little England, even though these areas spoke English. Fenton noted that Flemish names are rarely found in old documents. This supports Owen's idea that:

In the swaynes and laborers of the countrey you may often trace a Flemish origin...

But Fenton also said:

...from the first introduction of foreigners into this country, the greater proportion were Saxon or English, whom the first Norman kings were as desirous of getting rid of as they afterwards were of the Flemish; and to that may be ascribed the predominancy of the English language.

Fenton added that it's no surprise this part of the county, which was settled by English speakers and kept its own customs, was called Little England beyond Wales. It was even seen as part of England by law.

On the Gower Peninsula, the clear difference between English-speaking and Welsh-speaking people was called the "Englishry" and the "Welshry." As Owen mentioned, the cultural differences between Little England and the "Welshry" are more than just language. Villages with a lord's manor are more common in Little England, especially near the Daugleddau estuary. The north, however, has typical Welsh scattered homes. Farming methods are also different.

However, Little England and the Welshry also have many things in common. Common Welsh surnames (like Edwards, Richards, Phillips) were almost everywhere in the Welshry in Owen's time. But they also made up 40 percent of names in Little England. Today, most English-speaking people from Little England see themselves as Welsh. Gerald of Wales, who was born on the south coast in Manorbier in 1146, also felt this way.

More recently, David Austin has called "Little England" a myth. He believes the language difference came from a mix of land changes and the ambitions of powerful families during the Tudor period.

Genetic Studies

A Welsh expert named Morgan Watkin claimed that the levels of type A blood in South Pembrokeshire were 5–10 percent higher than in nearby areas. Watkin thought this was because of Viking settlers, not because King Henry I moved Flemish people there. However, a geneticist named Brian Sykes later said that while type A blood isn't especially high in Flanders, it's hard to tell if the high levels in "Little England" came from Vikings or Flemings. Sykes also found that there wasn't much Viking DNA in South Wales, which suggests Watkin's idea about Vikings causing the high type A blood levels was wrong.

A study in 2003 looked at DNA in Haverfordwest. It found that the people there had DNA similar to people in South West England.

In 2015, researchers found "surprisingly clear differences" in the DNA of people living in the north and south of Pembrokeshire.

See also

- Landsker Borderlands Trail – a long walking path through this region.

- Cultural relationship between the Welsh and the English

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |