Loren Miller (judge) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

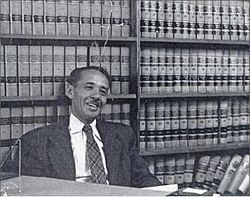

Loren Miller

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Judge of the Los Angeles County Superior Court | |

| In office 1964 – July 14, 1967 |

|

| Appointed by | Pat Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 20, 1903 Pender, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | July 14, 1967 (age 64) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Spouse | Juanita Ellsworth |

| Education | Washburn University (LLB) |

Loren Miller (born January 20, 1903 – died July 14, 1967) was an important American journalist, civil rights activist, lawyer, and judge. He was known for fighting for fairness and equal rights for all people.

In 1964, Loren Miller was appointed as a judge to the Los Angeles County Superior Court by Governor Edmund G. "Pat" Brown. He served as a judge until he passed away in 1967. Miller was especially good at fighting against unfair housing rules. His work helped shape the early Civil Rights Movement, making him famous for his strong efforts to give everyone, especially minorities, fair chances to find homes. He argued some very important civil rights cases in front of the Supreme Court of the United States. One of his biggest achievements was leading the case Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948. This case made it illegal to enforce rules that stopped people of certain races from buying homes.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Loren Miller was born in 1903 in Pender, Nebraska. His father, John Bird Miller, was born into slavery. His mother, Nora Herbaugh, was from Stoutland, Missouri, and had German and Irish heritage.

When Loren was a boy, his family moved to Kansas. He finished high school in Highland, Kansas. He then went to several universities, including the University of Kansas and Howard University. In 1928, he earned his law degree from Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. He became a lawyer in Kansas that same year. After practicing law there for a short time, he moved to California to work in journalism.

Career Highlights

In 1929, Loren Miller moved to Los Angeles, California. There, he started writing for the California Eagle, which was a weekly newspaper for the Black community. Miller later went back to practicing law and was allowed to practice in California in 1933.

His powerful writing during the Great Depression earned him a lot of respect in Los Angeles's Black community. People who knew him said he was so inspiring that other lawyers would sometimes delay their own cases just to hear him speak.

Fighting for Fair Housing

By the 1940s, Miller was actively working against rules and practices that discriminated against African Americans. After World War II, many Black people moved from the Southern states to California looking for better jobs. However, they often faced unfair treatment, especially when trying to find homes.

At that time, some neighborhoods had "restrictive covenants." These were agreements that stopped people of certain races from buying or renting homes in specific areas. Miller fought hard against these unfair rules. He won a case called Fairchild v. Raines in 1944. This case helped a Black family in Pasadena, California who were sued by white neighbors even though they had bought a lot without restrictions.

In 1945, Miller became the lawyer for famous Black stars like Hattie McDaniel, Louise Beavers, and Ethel Waters. They had moved to a part of Los Angeles known as "Sugar Hill." Some white residents tried to create a racial restriction agreement there. A judge visited the area and then threw the case out of court. The judge said it was time for Black people to have the full rights guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

By 1947, Miller had represented over a hundred people trying to get rid of these housing rules. He believed housing discrimination was a huge problem in the country. As a board member of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), he spoke out for the rights of minorities to have equal access to housing and education. He criticized the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) for policies that kept Black people in "tight ghettos," causing racial tension.

In 1948, Miller wrote that the FHA had even provided a model for race-restrictive clauses. He said that these rules did not create peace but instead led to "bitterness and strife." Miller was one of the first to see that housing bias would become a major social issue in the U.S.

Landmark Supreme Court Cases

Perhaps the most famous case Miller worked on was Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948. He worked with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall on this case. The Supreme Court of the United States decided that courts could not enforce racial rules on property. This was a huge victory for civil rights.

Later, Miller became a co-chair of the West Coast legal committee for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In this role, he was the first U.S. lawyer to win a clear decision that outlawed residential restrictive covenants when homes were financed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or Veterans Administration (VA).

In 1951, Miller bought the California Eagle newspaper, where he had worked before. Through his writing, he continued to be a strong voice for African Americans. He fought for full integration of Black people in all parts of society and protested all forms of Jim Crow discrimination. His main concerns included housing discrimination, police brutality, and unfair hiring in police and fire departments. He also wrote many articles for other important journals.

In April 1953, Miller successfully argued the case Barrows v. Jackson before the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court ruled that even though racial covenants were unconstitutional, people could not sue others for money if they broke these covenants. This further weakened the power of restrictive covenants.

In 1964, California Governor Pat Brown appointed Loren Miller as a Los Angeles Municipal Court Justice. He served as a judge until his death.

Author and Historian

In 1966, Judge Miller wrote a book called The Petitioners: The Story of the Supreme Court of the United States and the Negro. This book tells the important story of how the U.S. Supreme Court influenced the lives of African Americans from 1789 to 1965.

His book explains that for a long time, Black people had to ask the Supreme Court for help to get the same rights that other citizens took for granted. Miller wrote that the Court's response was not always fair at first. But starting in the mid-1930s, the Court began to change its mind and even became a leader in civil rights. The book gives a picture of how American society changed from the view of those who were often left out.

Legacy and Honors

After his death, Loren Miller was honored in many ways. In 1968, a new school in South Central Los Angeles was named Loren Miller Elementary School.

The Loren Miller Bar Association (LMBA) was started in August 1968 in Seattle, Washington. This group quickly began to fight against racism and unfairness affecting the African-American community.

In 1977, the prestigious Loren Miller Legal Services Award was created. This award is given every year to a lawyer who has worked hard for a long time to provide legal help to people who cannot afford it.

Personal Life

Loren Miller passed away in Los Angeles on July 14, 1967.

His son, Loren Miller, Jr., also became a judge in Los Angeles County, serving from 1975 to 1997. Loren Miller, Jr.'s daughter, Robin Miller Sloan, became a judge in 2003. This made her the first third-generation judge in the history of the California court system.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |