Macfarlane Burnet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Macfarlane Burnet

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Frank Macfarlane Burnet

3 September 1899 |

| Died | 31 August 1985 (aged 85) Port Fairy, Victoria, Australia

|

| Alma mater | University of Melbourne University of London |

| Known for | Acquired immune tolerance |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Royal Medal (1947) Albert Lasker Award (1952) James Cook Medal (1954) Copley Medal (1959) Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1960) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Virology |

| Doctoral advisor | John Charles Grant Ledingham |

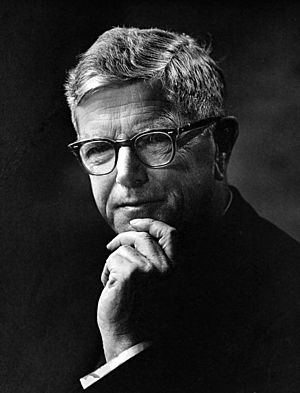

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet (3 September 1899 – 31 August 1985) was an important Australian scientist. He was known for his work in virology (the study of viruses) and immunology (the study of the body's defenses against disease). People often called him Macfarlane or Mac Burnet.

He won a Nobel Prize in 1960. This was for his ideas about how the body learns to accept or reject foreign things, called "acquired immune tolerance." He also created a big idea called the "clonal selection theory." This theory explains how our immune system creates specific defenses for different germs.

Burnet earned his first medical degree from the University of Melbourne in 1924. He then got his PhD from the University of London in 1928. He did a lot of groundbreaking research at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne. He was also the director of this important institute from 1944 to 1965.

After that, he worked at the University of Melbourne until he retired in 1978. He helped shape how medical science was managed in Australia. He was also a founder and president of the Australian Academy of Science.

Burnet made many discoveries in microbiology. He found the germs that cause diseases like Q-fever and psittacosis. He also created ways to find and grow the influenza virus. His work helped create modern influenza vaccines. These vaccines still use his methods for growing viruses in hen's eggs.

For his amazing work, Burnet was named the first Australian of the Year in 1960. He also received many international awards, including the Nobel Prize.

Contents

Early Life and Interests

Burnet was born in Traralgon, Victoria, Australia. His father, Frank Burnet, was a bank manager. His mother, Hadassah Burnet, was the daughter of Scottish immigrants.

From a young age, Mac loved exploring nature. He enjoyed looking at the environment around Traralgon Creek. He started school at age 7. Mac preferred reading and studying over sports.

In 1909, his family moved to Terang. Burnet was very interested in the wildlife around Lake Terang. He joined the Scouts in 1910 and loved outdoor activities. He started collecting beetles and studying biology. He read about Charles Darwin in an encyclopedia.

His family took holidays to Port Fairy every year. There, Burnet spent his time watching and writing about animals. He was a great student and won a scholarship to The Geelong College, a top private school. He started there in 1913. He didn't enjoy his time there much. He was quiet and loved books, while many of his classmates were loud and sporty. He kept his beetle collecting a secret.

Still, his strong academic skills helped him. He graduated in 1916 as the top student in his school. He chose to study medicine at university.

University and Early Career

In 1918, Burnet started at the University of Melbourne. He lived at Ormond College. He read more of Darwin's work and was inspired by the ideas of science from H. G. Wells. He loved spending time in the library, reading biology books.

He was a very motivated student. He often skipped lectures to study at his own speed in the library. He was first in physics and chemistry in his first year. In 1919, he was chosen for extra lessons. He also started working in hospitals. He was more interested in figuring out diseases than showing feelings to patients.

He graduated with two degrees in 1922. He then worked at Melbourne Hospital for ten months. He enjoyed working in surgery. However, the hospital's superintendent thought Burnet was better suited for laboratory research. So, Burnet became a senior resident pathologist.

In 1923, he started research at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research. He studied how the body reacts to typhoid fever. His work led to his first published scientific papers. He did so well in his Doctor of Medicine exams that his score was removed from the grading. This was so other students wouldn't fail for being so far behind him.

The Hall Institute was growing fast. The new director, Charles Kellaway, wanted to make it a world-class research center. He saw Burnet as a top young talent. Kellaway thought Burnet needed experience in England. So, Burnet went to London in 1925.

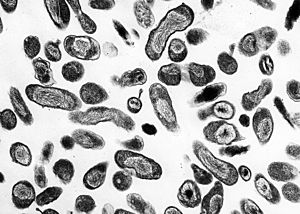

In London, he worked at the Lister Institute. He helped prepare bacteria for other scientists. In the afternoons, he did his own experiments. He studied how bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) affected mice. He believed bacteriophages were a type of viruses. For this work, he earned his PhD from the University of London in 1928.

While in London, Burnet met and got engaged to Edith Linda Marston Druce. They married in 1928 after he returned to Australia. They had one son and two daughters.

Work at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

When Burnet came back to Australia, he became the assistant director at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute. His first big task was to investigate the "Bundaberg tragedy." This was when 12 children died after getting a contaminated diphtheria vaccine. Burnet found the bacteria that caused the problem. This work made him very interested in immunology.

He continued to study bacteriophages. He and his assistant, Margot McKie, wrote a paper in 1929. They suggested that bacteriophages could exist in a hidden, non-infectious form. This idea, called lysogeny, was very important later for other Nobel Prize winners.

From 1932 to 1933, Burnet worked at the National Institute for Medical Research in London. There, he helped make big discoveries about the influenza virus. He developed a way to grow and study animal viruses using chick embryos. He turned down a permanent job offer in London to return to Australia. The Rockefeller Institute then gave money to build a new virus research lab for Burnet in Melbourne.

Back in Australia, he kept working on viruses. He also studied the causes of psittacosis and Q fever. The germ that causes Q fever was named Coxiella burnetii in his honor. He was the first person to catch Q fever in the lab! His studies showed how diseases spread in nature.

During World War II, Burnet focused on influenza and scrub typhus. He became the acting director of the Institute. He worked hard to find a vaccine for influenza. He tested a vaccine on soldiers, but it didn't work well enough. His work on vaccines earned him international fame.

In 1944, Burnet became the director of the Institute. He believed the Institute should focus on one main area of research at a time. He was a strong leader and expected his team to follow his plans. He chose all the research staff and students himself.

Under Burnet's leadership, the Institute made huge contributions to understanding infectious diseases. This time was called the "golden age of virology." Scientists there studied diseases like Murray Valley encephalitis, myxomatosis, and influenza.

Burnet made big advances in influenza research. He created ways to grow and study the virus. He also discovered a special enzyme called neuraminidase. This discovery helped other scientists understand how glycoproteins work. He also studied the genetics of influenza. He showed that the virus could mix and match its genes often.

Immunology Research

In 1957, Burnet decided the Institute should focus mainly on immunology. This decision caused some virologists to leave. But from then on, all new staff worked on immunology problems. Burnet studied autoimmune diseases (when the body attacks itself) and how the body reacts to transplanted tissues.

Burnet started focusing on immunology in the 1940s. In 1941, he wrote a book called "The Production of Antibodies." In this book, he introduced the important idea of "self" and "non-self" in immunology. This means the body knows what belongs to it ("self") and what doesn't ("non-self").

Using this idea, Burnet suggested how the body learns not to attack its own parts. This is called immune tolerance. He couldn't prove this himself. But in 1953, other scientists, including Peter Medawar, found proof. They showed that if you put certain cells into baby mice, the mice would accept skin from those cells later.

Burnet and Medawar shared the 1960 Nobel Prize for this work. Their discoveries helped make organ transplantation possible.

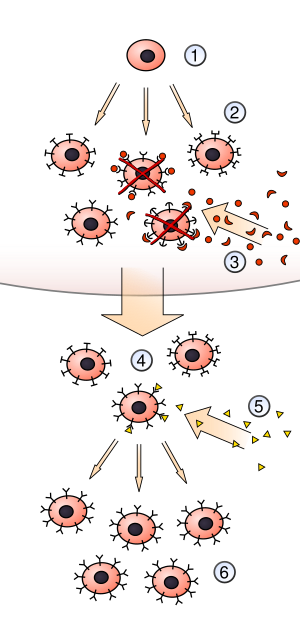

Burnet was also interested in how the body makes antibodies to fight germs. In 1956, he became interested in Niels Kaj Jerne's idea. Jerne suggested that antibodies find germs by chance. Then, when they connect, the body makes more of those specific antibodies.

Burnet expanded on Jerne's idea and called it the clonal selection theory. He proposed that each immune cell (lymphocyte) has a specific "receptor" on its surface. This receptor is like a lock for a specific germ. When a germ (antigen) comes along, it "selects" the right lymphocyte. That lymphocyte then makes many copies of itself to fight the germ.

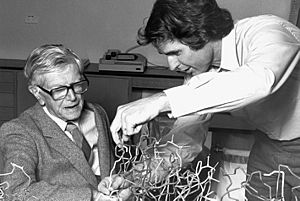

In 1958, Gustav Nossal and Joshua Lederberg showed that one type of immune cell (a B cell) makes only one type of antibody. This was the first proof for Burnet's clonal selection theory. Burnet wrote more about this theory in his 1959 book. His theory predicted many key features of our immune system today. He believed this was his greatest contribution to science.

Burnet also worked on "graft-versus-host" reactions. This happens when transplanted cells attack the new body. His work helped explain why this happens. His last project at the Institute was studying autoimmune disease in mice. He looked at how these diseases are passed down. He also used a drug to treat the disease in mice. This influenced how drugs are used for human autoimmune diseases.

In 1960, Burnet started spending more time writing. In 1963, he published a book on autoimmune diseases. He also helped expand the Hall Institute building. He believed a world-class research center should be small enough for one person to lead effectively. He kept tight control over the Institute's work.

He continued working in the lab until he retired in 1965. Under his leadership, the Hall Institute became a world-famous center for immunology.

Public Health and Policy

From 1937, Burnet became involved in science and public policy. He advised the government on health issues. After becoming director of the Hall Institute in 1944, he became a public figure. He learned to be a good public speaker. He understood that working with the media was important. This helped the public understand science.

His writings and talks helped shape public opinion in Australia. He appeared on radio and television. He felt it was his duty as a scientific leader to speak out.

Burnet served on many scientific committees in Australia and overseas. He advised on funding for medical research. He was also chairman of the Australian Radiation Advisory Committee. He was worried about people being exposed to too much radiation.

Internationally, Burnet advised on medical research in Papua New Guinea. He was very interested in human biology. He helped set up the Papua New Guinea Institute of Human Biology. He also worked with the World Health Organization.

In 1964, he joined the University Council of La Trobe University. He wanted less strict relationships between professors and students. He also thought liberal arts should be less important. His ideas were too radical for others, so he left the role in 1970.

Burnet was against using nuclear power in Australia. He was worried about the spread of nuclear weapons. Later, he changed his mind about uranium mining in Australia. He felt nuclear power was needed while other energy sources were developed.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, he spoke out against smoking. He was one of the first famous Australians to warn the public about tobacco. He even appeared in a TV ad criticizing tobacco advertising. He had quit smoking himself after friends died from it. Burnet also spoke out against the Vietnam War. He called for an international police force.

Later Life and Legacy

After leaving the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Burnet worked at the University of Melbourne. He wrote 13 books on topics like immunology, aging, and cancer. He also wrote his autobiography, Changing Patterns, in 1968. He wrote 16 more books after he retired. He was known for writing quickly and clearly.

He became president of the Australian Academy of Science in 1965. He had been a founding member in 1954. As president, he was seen as Australia's top scientist. His reputation helped solve policy disagreements. He made the Academy more respected by the government and industry.

He helped create the Academy's Science and Industry Forum. This group aimed to improve talks between researchers and businesses. It led to the creation of the Australian Science and Technology Council. He also helped start the Australian Biological Resources Study. When his presidency ended in 1969, the Academy created the Macfarlane Burnet Medal and Lecture in his honor. This is the Academy's highest award for biological sciences.

Burnet's later writings sometimes caused arguments in the scientific community. He often made gloomy predictions about the future of science. In 1966, he questioned the usefulness of molecular biology. He argued it wouldn't help medicine much.

He spoke and wrote a lot about human biology after he retired. He wanted to reach all parts of society. He often talked to the media.

Personal Life

Burnet was married twice. His first wife was Edith Linda Druce. They married in 1928 and had one son and two daughters. Edith died in 1973 after a four-year illness. In 1976, he married Hazel Gertrude Jenkin. Hazel was a widow who worked as a librarian in the microbiology department.

Later Years and Death

Burnet officially retired in 1978. He wrote two more books in retirement. He missed his laboratory work. In 1982, he contributed to a book called Challenge to Australia. He wrote about genetic issues. In 1983, he was appointed to the Australian Advisory Council of Elders. This group advised policymakers.

Burnet continued to travel and speak. But in the early 1980s, he and his wife became ill more often. In November 1984, he had surgery for colorectal cancer. He died on 31 August 1985, at his son's home in Port Fairy.

He received a state funeral from the Australian government. Many of his famous colleagues were pall-bearers. He was buried near his grandparents in Koroit. The Australian Parliament honored him after his death.

Honours and Legacy

Burnet received many honors for his contributions to science and public life. He was knighted in 1951. He received the Order of Merit in 1958. In 1960, he was the first person to receive the Australian of the Year award. He also received an award from Japan in 1961. In 1978, he was made a Knight of the Order of Australia. He was only the fourth person to receive this high honor.

He was a member or honorary member of 30 international science academies. He received 10 honorary science degrees from universities like Cambridge, Harvard, and Oxford. He also received 19 medals and awards, including the Nobel Prize. He gave many lectures in Australia and around the world.

After his death, Australia's largest infectious disease research institute was renamed the Macfarlane Burnet Centre for Medical Research in his honor. The Burnet Clinical Research Unit at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute was also named after him. In 1975, his work was recognized on an Australia Post stamp. He also appeared on a stamp with fellow scientist Jean Macnamara in 1995. In 1999, a statue of him was put up in Traralgon to celebrate 100 years since his birth.

Burnet's biographer, Christopher Sexton, says Burnet's legacy is fourfold:

- The high quality of his research.

- His choice to stay in Australia, which helped Australian science grow.

- His success in making Australian medical research famous worldwide.

- His many books and writings.

Even with some of his controversial ideas, Peter C. Doherty noted that "Burnet's reputation is secure in his achievements as an experimentalist, a theoretician and a leader of the Australian scientific community."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Frank Macfarlane Burnet para niños

In Spanish: Frank Macfarlane Burnet para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |