Peter Medawar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Peter Medawar

|

|

|---|---|

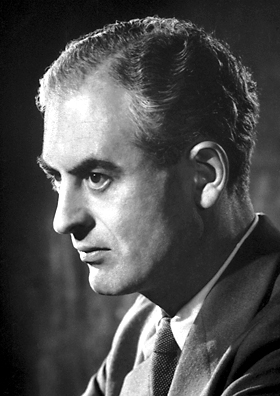

Peter Medawar, 1960

|

|

| Born |

Peter Brian Medawar

28 February 1915 |

| Died | 2 October 1987 (aged 72) |

| Citizenship | British Brazilian (resigned) |

| Education | Magdalen College, Oxford (BA, DSc) |

| Known for | Immunological tolerance Organ transplantation |

| Spouse(s) |

Jean Medawar (née Taylor)

(m. 1937) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Growth promoting and growth inhibiting factors in normal and abnormal development (1941) |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students | Rupert E. Billingham (postdoc) |

| Influences | |

Sir Peter Brian Medawar (28 February 1915 – 2 October 1987) was an important Brazilian-British scientist and writer. He is famous for his work on how the body accepts or rejects new tissues, like in organ transplants. His discoveries about how our immune system can learn to accept foreign tissues were very important for modern medicine. Because of his work, he is often called the "father of transplantation."

Peter Medawar was also known for his cleverness and humor. Other famous scientists, like Richard Dawkins, called him "the wittiest of all scientific writers." He shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of "acquired immunological tolerance." This means the immune system can be taught to accept certain new things.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Peter Medawar was born in Petrópolis, a town near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His father was from Lebanon, and his mother was British. He was the youngest of three children. His father worked for a company that sold dental supplies. Peter was a citizen of both Brazil and Britain from birth.

He moved to England with his family when he was young and lived there for the rest of his life. When he was 18, he had to choose between his Brazilian and British citizenship. He decided to give up his Brazilian citizenship.

In 1928, Peter went to Marlborough College in England. He didn't always enjoy his time there, but he loved his biology classes. His teacher, Ashley Gordon Lowndes, helped him start his career in biology. Peter said Lowndes was a "very, very good biology teacher."

In 1932, he went to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied zoology. He graduated with top honors in 1935. At Oxford, he worked with Howard Florey, who later won a Nobel Prize. Florey inspired Peter to study immunology, which is the study of the body's defense system. Peter also helped invent a "nerve glue" that was useful for treating injured soldiers during World War II. He earned his Doctor of Science degree in 1947.

Career and Research

After finishing his studies, Peter Medawar continued his scientific career. He became a professor of zoology at the University of Birmingham in 1947. Later, in 1951, he moved to University College London.

In 1962, he became the director of the National Institute for Medical Research. This was a very important job in medical science. He also led the transplantation section of the Medical Research Council for many years.

Understanding the Immune System

Peter Medawar's most important work began during World War II. He was trying to find better ways to do skin grafts for soldiers with severe burns. He published his first paper on skin grafts in 1941.

His research became more focused in 1949. Another scientist, Frank Macfarlane Burnet, suggested an idea. Burnet thought that very young animals, like embryos or newborns, could learn to tell the difference between their own body tissues and foreign materials.

Medawar, along with his student Leslie Brent and fellow researcher Rupert Billingham, decided to test Burnet's idea. They took cells from young mouse embryos and put them into another mouse of a different type. When the second mouse grew up, they tried to give it a skin graft from the first type of mouse. Normally, the mouse's body would reject this foreign skin. But in their experiment, the mouse accepted the new skin! This meant the mouse's immune system had learned to tolerate the foreign tissue.

They called this discovery "actively acquired tolerance." Their findings were first published in 1953 and later in more detail in 1956. This work became the basis for all modern organ transplants.

Impact of His Discoveries

Peter Medawar and Frank Macfarlane Burnet shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They won for their discovery of how the immune system can learn to accept foreign tissues. This breakthrough changed the field of immunology.

Before their work, scientists focused on how the immune system fought off foreign things. Medawar's research showed that it was possible to change the immune system itself. This opened the door for doctors to perform the first successful organ transplants in humans. An American doctor named Joseph Murray performed these transplants and later won a Nobel Prize for his work.

Why We Age

Peter Medawar also thought about why living things grow old, a process called senescence. He wondered why evolution would allow aging, even though it makes individuals weaker.

He suggested that the power of natural selection becomes weaker as an organism gets older. This is because the ability to have babies when young is much more important for passing on genes. What happens to an organism after it has reproduced doesn't affect the next generation as much. His ideas helped form the basis for modern theories about why we age.

Personal Life

Peter Medawar married Jean Shinglewood Taylor in 1937. They met while studying at Oxford University. Jean's family was initially against their marriage because Peter didn't have a lot of money or a well-known background.

Peter was very tall, about 6 feet 5 inches (196 cm), and had a loud voice. He was known for his quick wit and humor. He was interested in many things, including opera, philosophy, and cricket. He was also a follower of the philosopher Karl Popper. Peter Medawar was the grandfather of the famous screenwriter and director Alex Garland.

Views on Beliefs

Peter Medawar respected many aspects of Christianity, especially its moral teachings. However, he found some stories in the Bible to be unethical. He even asked his wife to make sure their children didn't read such stories.

Later Life and Death

In 1959, Peter Medawar gave a series of radio talks for the BBC called The Future of Man. In these talks, he explored how humans might continue to evolve.

In 1969, Peter Medawar suffered a stroke. This affected his speech and movement. It was a difficult time, but with his wife's help, he continued to write and do research, though on a smaller scale. He had more health problems later and passed away in 1987 in London. He is buried with his wife in a churchyard in East Sussex.

Awards and Honors

Peter Medawar received many awards for his important scientific work:

- He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1949.

- He shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Frank Macfarlane Burnet.

- The British government honored him with the CBE in 1958.

- He was knighted in 1965, becoming "Sir Peter Medawar."

- He was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honour in 1972 and the Order of Merit in 1981.

- He received the Royal Medal in 1959 and the Copley Medal in 1969 from the Royal Society.

- He was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science from 1968 to 1969.

- In 1985, he received the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for making science popular.

- He was awarded the 1987 Michael Faraday Prize for his books that explained science to the public.

Several awards and buildings are named after him:

- The Royal Society has the Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Lecture and Medal.

- The British Transplant Society awards the Medawar Medal for research in organ transplantation.

- The University of Oxford has the Peter Medawar Building for Pathogen Research.

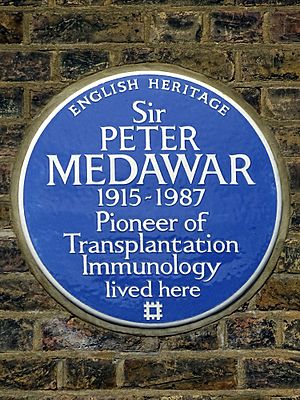

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Peter Brian Medawar para niños

In Spanish: Peter Brian Medawar para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |