Howard Florey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Florey

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Howard Walter Florey

24 September 1898 Adelaide, South Australia

|

| Died | February 21, 1968 (aged 69) Oxford, England

|

| Education | Scotch College, Adelaide, St Peter's College, Adelaide |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Discovery of penicillin |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Bacteriology, immunology |

| Institutions | |

| Influences | Charles Sherrington |

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (born September 24, 1898 – died February 21, 1968) was an Australian scientist. He was a pharmacologist (someone who studies how medicines work) and a pathologist (someone who studies diseases). In 1945, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming. They won this award for their amazing work in developing penicillin.

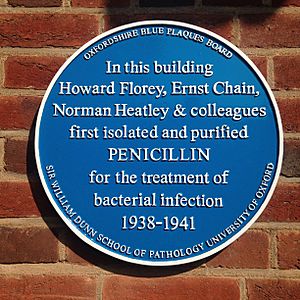

While Alexander Fleming first discovered penicillin, it was Florey and his team at the University of Oxford who turned it into a powerful medicine. They found ways to grow, clean, and make the drug. They also figured out its chemical structure and how it fought off infections. Their tests on animals and the first human trials showed how effective penicillin was. In 1941, they used it to treat a police officer. He started to get better, but sadly died because they couldn't make enough penicillin at that time. Later trials in Britain, the United States, and North Africa were very successful.

Florey went to the University of Adelaide and then studied at the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. He also studied in the United States. In 1935, he became the head of the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford. He brought together a diverse team of scientists to work on big research projects. Besides penicillin, he also studied other important things like lysozyme and cephalosporin. He helped start the Australian National University in Canberra and its John Curtin School of Medical Research. He was also the leader (Chancellor) of the Australian National University from 1965 until he passed away in 1968. He became a member of The Royal Society in 1941 and was its president from 1960 to 1965.

It's believed that Florey's discoveries have saved over 80 million lives. Many Australian scientists and doctors see him as one of their greatest figures. Sir Robert Menzies, a former Australian Prime Minister, once said that Florey was "the most important man ever born in Australia" because of his global impact.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Howard Walter Florey was born in Malvern, a suburb of Adelaide, South Australia, on September 24, 1898. His last name sounds like "sorry." He was the only son of Joseph Florey, a shoemaker from England. Joseph had two older daughters from his first marriage. After his first wife became ill, the family moved to South Australia, hoping the climate would help her. She passed away in 1886. Joseph then married Bertha Mary Waldham, and they had two daughters, Hilda and Valetta. So, Howard had two older sisters and two older half-sisters.

In 1906, his family moved to a large house in Mitcham. Howard went to Unley Park School, a local private school. He often rode a horse-drawn tram to school. At school, he got the nickname "Floss," which stayed with him for life. He later attended Kyre College and then St Peter's College, Adelaide. At St Peter's, he was excellent in science and math. He also played many sports like cricket and Australian football. Scholarships helped pay for his education. He wanted to join the army during World War I, but his parents wouldn't let him. He was a top student in his final year.

Instead of becoming a businessman like his father, Florey decided to study medicine, following his sister's path. He started at the University of Adelaide in March 1917, with his fees covered by a scholarship. This was lucky because his father died in 1918, and his shoe company went out of business. Howard met Mary Ethel Hayter Reed, another medical student, while working on the university magazine.

Studying at Oxford

Florey wanted to do medical research, which meant he needed to study overseas. In 1920, he applied for a Rhodes Scholarship to study at the University of Oxford in England. He was chosen for this great honor, which came with money to support him. He insisted on finishing his medical exams in Australia before starting at Oxford in January 1922. He earned his medical degree in December 1921.

On December 11, 1921, Florey sailed to England. He traveled for free as the ship's doctor. In Oxford, he chose to study at Magdalen College, Oxford. He focused on physiology (the study of how the body works) under Sir Charles Scott Sherrington. During his summer breaks, he traveled around Europe. He became a teaching assistant in the physiology department. In 1924, he earned his Bachelor of Arts degree. He also studied the brains of cats and wrote a thesis on blood circulation, earning a Bachelor of Science degree in 1925.

Florey then received a scholarship to study at the University of Cambridge. In 1925, he won another scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation to study in the United States. He worked at the University of Pennsylvania and later at Cornell University Medical College. He returned to the UK in May 1926 and married Ethel Reed in October.

Building a Research Team

Florey wasn't happy at London Hospital because of the long commute and poor facilities for his animal experiments. He continued his research on how the body's fluids move. He also wrote a thesis for a fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, which he received in 1927.

Cambridge and Sheffield

Florey moved to the University of Cambridge for a secure teaching and research job. He didn't enjoy teaching as much as research. There, he hired a fourteen-year-old assistant named Jim Kent, who stayed with him for forty years. Florey was known for working hard and having high standards. The Floreys bought a house in Cambridge. Ethel, his wife, also helped with some research papers. In 1929, their daughter Paquita was born.

Later, Florey moved to the University of Sheffield in 1932 to become a professor of pathology. He took Jim Kent with him. The university raised his salary to keep him when he received another job offer. Florey's main interest was lysozyme, a substance that kills certain bacteria. He also researched tetanus and the lymphatic system. His son, Charles du Vé, was born in Sheffield in 1934.

Oxford and Penicillin

In 1935, Florey became the Professor of Pathology at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford. The laboratory building was large but had few staff. Florey kept some existing staff and brought Jim Kent and Beatrice Pullinger with him. He also hired Margaret Jennings to study mucus. He attracted talented students and researchers, including Rhodes Scholars.

Florey wanted a good bacteriologist and a biochemist for his team. He convinced Arthur Duncan Gardner to lead his bacteriology section. For biochemistry, he tried to get several people before Ernst Boris Chain was recommended. Chain was a Jewish refugee from Germany. Florey offered him a one-year position. Chain then suggested Norman Heatley as a collaborator, and Florey arranged funding for Heatley's position.

In 1936, Florey visited Australia with his family to see his mother, who was ill. He also met other scientists there. From then on, Florey led a unique interdisciplinary team. This meant different scientists worked together on one big problem, each tackling a different part. This was a new way of working in the UK at the time. Florey encouraged discussion but didn't hold formal team meetings. He would visit each lab daily to check on progress.

One of their first big projects was studying lymphocytes, which are important cells in the immune system. Florey also continued his work on lysozyme. His team successfully purified and crystallized lysozyme, figuring out how it worked. However, they found that lysozyme only killed bacteria that didn't cause illness, so it wasn't useful as a medicine.

The Penicillin Breakthrough

Discovering its Power

While working on lysozyme, Ernst Chain read a paper by Alexander Fleming about a mold called Penicillium notatum that killed bacteria. Chain thought it might be similar to lysozyme. Money was tight, but Florey and Chain decided to start a big research project on substances made by tiny living things (micro-organisms) that could fight bacteria. Penicillin was one of the substances they chose.

In September 1939, after World War II began, Florey got some funding for the project. The team already had a sample of the penicillin mold, which had been given to the lab years earlier by Fleming. The team developed ways to grow the mold in glass bottles. They hired six women to help with this work, which had to be done in very clean conditions. They found that some airborne bacteria could destroy penicillin.

Norman Heatley and Ernst Chain worked on how to get penicillin out of the mold. They filtered the liquid and then used a special method called "reverse extraction" to separate the penicillin. Chain also came up with the idea of freeze drying to get a dry, brown powder of penicillin without damaging it. This meant the team had a complete process for growing, extracting, and purifying penicillin.

The team also showed that penicillin could kill many different types of bacteria, including those that cause gonococcus , meningococcus, streptococcus, staphylococcus, anthrax, tetanus, and gangrene. Florey and Margaret Jennings tested penicillin on animals and found it wasn't harmful. In May 1940, they injected mice with a deadly bacteria. The mice given penicillin survived, while the others died. They repeated these experiments, confirming penicillin's effectiveness. They published their findings in The Lancet in August 1940.

In February 1941, Florey and Chain treated their first human patient, Albert Alexander, a police officer with a severe infection. He started to recover quickly after receiving penicillin. However, they didn't have enough penicillin to fully cure him, and he sadly died. Because of this, Florey decided to focus on treating children, who needed smaller amounts of the drug. Florey was disappointed that his work didn't get more attention at first.

Making Penicillin for Everyone

As the war continued, Florey and Heatley traveled to the United States in June 1941. They wanted to find a way to produce penicillin in large amounts. They met with scientists and government officials, including those at the Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL) in Peoria, Illinois. There, they learned about "deep submergence" fermentation, a way to grow penicillin in huge tanks.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the United States into the war, making penicillin production even more urgent. While Chain suggested getting a patent for the penicillin process, Florey and others disagreed, believing scientists shouldn't profit from life-saving discoveries. However, the Americans did patent their large-scale production methods.

Back in the UK, penicillin production increased. Florey led more clinical trials. His wife, Ethel, helped manage these trials. Even though doctors often sent very sick patients, penicillin still worked, building confidence in the drug. A newspaper article about a successful case caused a stir, as Florey wanted to keep supplies for trials. The British government then gave penicillin mass production top priority. In March 1943, Ethel and Howard Florey published the successful results of 187 cases treated with penicillin.

Penicillin in War Zones

The Medical Research Council decided it was time to test penicillin in real war situations. Florey went to North Africa in May 1943, where the North African campaign was happening. He worked with Hugh Cairns, a British Army brigadier. They treated over a hundred soldiers with old, unhealed wounds. Florey also gave lectures on penicillin and recommended new ways to treat wounds, suggesting they be cleaned and sealed quickly, relying on penicillin to prevent infection. This was a very new idea at the time. His recommendations were put into practice, and training courses were set up for medical officers. With improved supply, two out of three soldiers with gas gangrene now survived.

In 1944, Florey visited the Soviet Union and Australia to share his knowledge of penicillin. In Australia, he was welcomed as a hero. He learned that Australia was already producing penicillin, which pleased him, but he was surprised they hadn't asked him for advice.

Recognition for His Work

Florey returned to the UK in October 1944. By 1945, penicillin was being produced on a massive scale for the Allies in World War II. Florey always said the project was driven by scientific curiosity, and its medical use was a bonus. He was knighted in 1944 and shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Ernst Boris Chain and Alexander Fleming.

While Fleming first noticed penicillin's effects, it was Chain and Florey who developed it into a usable medicine. Florey always stressed that it was a team effort, but he was the one who built and led that team. He turned down a large personal gift of money, asking instead for it to be used to create research scholarships at his school. He also arranged for a rose garden and memorial stone to honor his entire team.

Later Life and Legacy

New Antibiotics

After the war, Florey's team continued to study other substances that could fight infections. They published a huge two-volume book called Antibiotics in 1949. In 1953, two of his team members, Guy Newton and Edward Abraham, found a new antibiotic called cephalosporin C. Even though it didn't seem very strong at first, Florey encouraged them to keep working on it. They discovered it could fight bacteria that were resistant to penicillin. Florey and Jennings then showed it wasn't harmful to mice and could protect them from infections. This work led to the creation of many new cephalosporin medicines, which became very important.

Helping Australian Science

Florey played a key role in setting up the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. In 1945, he proposed a medical research institute for Australia. The Australian National University Act was passed in 1946, creating the ANU and its John Curtin School of Medical Research. Florey became the acting director of this school in 1948 to help establish it.

He helped design the building and hired top scientists like Hugh Ennor, Adrien Albert, and Frank Fenner. The building was very expensive and complex to equip with world-class laboratories. Florey visited Canberra in 1953 and, though he didn't want to be the permanent director, he agreed to continue as an advisor. The John Curtin School of Medical Research officially opened in 1958. In 1964, Florey became the leader (Chancellor) of the Australian National University, a role he held until his death in 1968.

Leading the Royal Society

Florey was elected a member of the prestigious Royal Society in 1941. He served on its council and received important awards like the Royal Medal and the Copley Medal. In 1960, he became the President of the Royal Society. He worked to find a new, larger home for the society at Carlton House Terrace in London, which was opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1967.

Florey wanted the Royal Society to be more modern and international. He hosted famous visitors like Yuri Gagarin and led visits to Russia. He also helped create new research professorships and lecture series. Aware that life-saving drugs could lead to overpopulation, he started a group to study population and became president of the Family Planning Association.

Provost of Queen's College

As he got older, Florey faced retirement from his university position. He accepted the role of Provost (head) of The Queen's College, Oxford in 1962. This meant leaving his chair at the Sir William Dunn School. He was the first Provost of Queen's College who hadn't studied there before, and the first scientist. He used his position to host visiting scientists.

Based on his own experience, Florey created a scholarship program for European students to study at Oxford. He raised money for these scholarships, which helped many students. He also led a major building project for new student housing at the college. The main building, designed by Sir James Stirling, was named the Florey Building in his honor after he passed away. Other buildings in Australia were also named after him.

Awards and Honours

Florey received many awards for his contributions to science and medicine. In 1945, he won the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh and the Lister Medal. He also received many honorary degrees from universities around the world. He was given the Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1947. He became a commander of the French Legion of Honour in 1946 and received the American Medal for Merit in 1948.

He was elected to important scientific groups in the United States, including the National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society in 1963. In 1965, Florey was made a life peer, becoming Baron Florey. This was a very high honor, recognizing his huge role in making penicillin available to save millions of lives. He was also appointed a member of the Order of Merit in 1965.

Death

Florey's first wife, Ethel, became very ill and passed away in October 1966. On June 6, 1967, Florey married Margaret Jennings in a quiet ceremony. He published his last scientific paper with Jennings in 1967. He had written or co-written over two hundred papers during his career.

Howard Florey died at his home in Oxford on February 21, 1968, from heart failure. A funeral service was held, and a memorial plaque was placed on the outside wall of the church. A larger service was held at Westminster Abbey in London. His remains were cremated. In 1981, a memorial stone made of South Australian marble was unveiled in London to honor him.

Lasting Impact

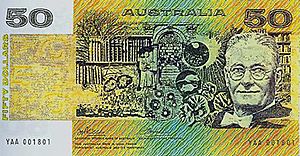

Howard Florey's face appeared on the Australian fifty-dollar note for 22 years, from 1973 to 1995. The note also showed images related to his work, like the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, the penicillin mold, and mice used in his experiments. Many places are named after him, including Florey Drive and the suburb of Florey in Australia, the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne, and a lecture theatre at the University of Adelaide. It's estimated that the development of penicillin saved over 80 million lives, making his work one of the most important medical achievements in history.

In Film

Florey's story has been told in films. Penicillin: The Magic Bullet is a 2006 Australian film about his work. Breaking The Mould is a 2009 historical drama that shows the story of penicillin's development by Florey's team at Oxford. The film stars Dominic West as Florey.

Images for kids

-

John Eccles, Adrien Albert, Frank Fenner and Hugh Ennor study the plans for the John Curtin School of Medical Research

See also

In Spanish: Howard Walter Florey para niños

In Spanish: Howard Walter Florey para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |